Forgotten Journey

Silvina Ocampo

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan

San Francisco: City Lights, 2019

The Promise

Silvina Ocampo

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell

San Francisco: City Lights, 2019

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 100 (June 2020)

It seems, at long last, that Silvina Ocampo (1903-1993) may be having her moment among US readers and publishers. With the crisp new City Lights editions, six books of her work are now available in English, three of them co-translated by Suzanne Jill Levine (who translated most of Adolfo Bioy Casares’s books, among many others, and co-translated the mock detective novel penned by Bioy and Silvina in 1946, Where There’s Love, There’s Hate). The new books neatly frame her writing life, from her first collection, Forgotten Journey, stories published in 1937 by older sister Victoria Ocampo’s press Sur, to her final enterprise, The Promise, a short novel that appeared posthumously and was her longest work of fiction.

Early to late in Silvina’s writing, one finds the same playfulness, stubborn curiosity, and a quirky resourcefulness. These are qualities that all her characters share, who often are children or else servants, caretakers, secondary figures in the life around them. Like the girl in the title story of her first book—who tries to remember all the way back to her own birth and persists in believing that babies are stocked in a big store in Paris before they are born—her protagonists maintain against all odds a sense of wonderment at the world. Such is the narrator’s outlook even in The Promise after she’s fallen overboard from a transatlantic ship and lying there in the middle of the ocean recalls a growing constellation of characters she has known, in rehearsal for the life story she intends to write if miraculously she survives.

Silvina Ocampo’s novel, which took a very long time to come into existence, turns out to be among the more singular works of literature. She started writing it in the mid-1960s, and returned to it intermittently until the late 1980s when she made a last effort to finish it before dementia set in; the book itself was first published only in 2010. For the woman stretched out on the open sea, her plight couldn’t be more dire (though she does come upon a battered raft, briefly, with its sampling of fresh fruit wrapped in paper)—and yet she goes on cheerfully revisiting her personal theater, her ghost theater. With each recollection that surfaces, she reflects on her immediate circumstances, calmly considering what awaits her at the bottom of the sea. As the characters proliferate, their connections to her ever more tenuous, it is clear she is also struggling to keep hold of a certain coherence, even as she feels her very identity dissolving. Her tale is the promise she made to Saint Rita, in the event she were to be saved, while admitting: “I don’t have a life of my own; I have only feelings. My experiences were never important . . . Instead, the lives of others have become mine.” As if her own Scheherazade, she keeps herself afloat by these stories.

In her fiction, Ocampo always showed a remarkable instinct for setting the tone of a character, a place, a preoccupation, with a nimble economy of lines. Her early training as a painter abetted that talent, as did her parallel practice as a poet. She describes one character in her first book: “The conductor of No. 15 had the same mustache as a manikin in a Flores department store—he was born there and grew very tall on the second floor of the store, until he became a streetcar driver” (“Where the Streetcars Sleep”). The twenty-eight stories of Forgotten Journey veer easily from a sort of local realism to a language of dreams or folk tales with ominous shadows, and that was the palette she generally employed through her subsequent half-dozen books of short fiction. An amusing inversion of registers, therefore, distinguishes the stories that make up much of the novel since they dwell in a basically realistic mode, like so many bubbles of life in all its ordinariness with its yearnings and jealousies and endless details—in contrast to the situation of the woman lost at sea recalling them.

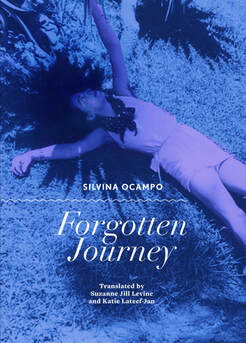

The translators have graced us with finely nuanced versions of these books that track the distinctive nature of Ocampo’s prose, plain spoken yet full of surprises, where mischief or tenderness or even illumination may emerge at any moment. What’s more, the paired editions signal not only a smart design concept, with their vintage photos of Silvina on the cover (to echo the Lumen series of reissues and posthumous collections of her work, edited by Ernesto Montequin in Buenos Aires), but also serve to reintroduce her imaginative world to a North American public. The uninitiated reader would do very well to plunge in here. And for those who have read her: she is one of those writers, there is always room for more Silvina Ocampo books.

Silvina Ocampo

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Katie Lateef-Jan

San Francisco: City Lights, 2019

The Promise

Silvina Ocampo

Translated by Suzanne Jill Levine and Jessica Powell

San Francisco: City Lights, 2019

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 100 (June 2020)

It seems, at long last, that Silvina Ocampo (1903-1993) may be having her moment among US readers and publishers. With the crisp new City Lights editions, six books of her work are now available in English, three of them co-translated by Suzanne Jill Levine (who translated most of Adolfo Bioy Casares’s books, among many others, and co-translated the mock detective novel penned by Bioy and Silvina in 1946, Where There’s Love, There’s Hate). The new books neatly frame her writing life, from her first collection, Forgotten Journey, stories published in 1937 by older sister Victoria Ocampo’s press Sur, to her final enterprise, The Promise, a short novel that appeared posthumously and was her longest work of fiction.

Early to late in Silvina’s writing, one finds the same playfulness, stubborn curiosity, and a quirky resourcefulness. These are qualities that all her characters share, who often are children or else servants, caretakers, secondary figures in the life around them. Like the girl in the title story of her first book—who tries to remember all the way back to her own birth and persists in believing that babies are stocked in a big store in Paris before they are born—her protagonists maintain against all odds a sense of wonderment at the world. Such is the narrator’s outlook even in The Promise after she’s fallen overboard from a transatlantic ship and lying there in the middle of the ocean recalls a growing constellation of characters she has known, in rehearsal for the life story she intends to write if miraculously she survives.

Silvina Ocampo’s novel, which took a very long time to come into existence, turns out to be among the more singular works of literature. She started writing it in the mid-1960s, and returned to it intermittently until the late 1980s when she made a last effort to finish it before dementia set in; the book itself was first published only in 2010. For the woman stretched out on the open sea, her plight couldn’t be more dire (though she does come upon a battered raft, briefly, with its sampling of fresh fruit wrapped in paper)—and yet she goes on cheerfully revisiting her personal theater, her ghost theater. With each recollection that surfaces, she reflects on her immediate circumstances, calmly considering what awaits her at the bottom of the sea. As the characters proliferate, their connections to her ever more tenuous, it is clear she is also struggling to keep hold of a certain coherence, even as she feels her very identity dissolving. Her tale is the promise she made to Saint Rita, in the event she were to be saved, while admitting: “I don’t have a life of my own; I have only feelings. My experiences were never important . . . Instead, the lives of others have become mine.” As if her own Scheherazade, she keeps herself afloat by these stories.

In her fiction, Ocampo always showed a remarkable instinct for setting the tone of a character, a place, a preoccupation, with a nimble economy of lines. Her early training as a painter abetted that talent, as did her parallel practice as a poet. She describes one character in her first book: “The conductor of No. 15 had the same mustache as a manikin in a Flores department store—he was born there and grew very tall on the second floor of the store, until he became a streetcar driver” (“Where the Streetcars Sleep”). The twenty-eight stories of Forgotten Journey veer easily from a sort of local realism to a language of dreams or folk tales with ominous shadows, and that was the palette she generally employed through her subsequent half-dozen books of short fiction. An amusing inversion of registers, therefore, distinguishes the stories that make up much of the novel since they dwell in a basically realistic mode, like so many bubbles of life in all its ordinariness with its yearnings and jealousies and endless details—in contrast to the situation of the woman lost at sea recalling them.

The translators have graced us with finely nuanced versions of these books that track the distinctive nature of Ocampo’s prose, plain spoken yet full of surprises, where mischief or tenderness or even illumination may emerge at any moment. What’s more, the paired editions signal not only a smart design concept, with their vintage photos of Silvina on the cover (to echo the Lumen series of reissues and posthumous collections of her work, edited by Ernesto Montequin in Buenos Aires), but also serve to reintroduce her imaginative world to a North American public. The uninitiated reader would do very well to plunge in here. And for those who have read her: she is one of those writers, there is always room for more Silvina Ocampo books.