Repeat Play

Beckett on Film

Dublin: Blue Angel Films, 2001

published in American Book Review (Normal, IL) 24:5 (July-Aug. 2003)_

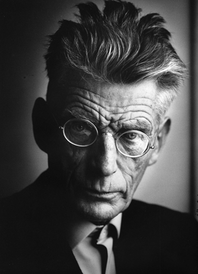

Does the rigor of Samuel Beckett’s plays demand that they be appreciated only in a straight-back chair? Might an audience be allowed to get comfortable, even in the ease of one’s own home? And what happens when the theater hall shrinks to the size of a living room, the viewer divorced by a TV screen from the actors who are not there? What a sacrilege to film Beckett’s plays, now that he’s been dead a while and can no longer object, and yet what a terrific opportunity.

Beckett on Film is a laudable project, unique in the realm of theater. Produced in Ireland and shot during the year 2000, the four-DVD set presents all nineteen of Beckett’s stage plays filmed by nineteen directors who remain faithful to his texts while probing the resources of their medium. We know the arguments: theater is performed live, before a different public each night, and so the shifting nuances, the shared risk and mutual response. The theatrical space is like a temple, where the spirit must be conjured up anew, collectively. Film offers none of that; its magic is more mechanical, engineered by a particular syntax of the gaze. What, then, is gained by such an enterprise?

Most obviously, a sense of intimacy. But Beckett’s plays are already intimate, often featuring a single character and never more than three or four, with their deep subterranean river of consciousness giving rise to the voices. Film, however, brings the possibility of the close-up. In Not I, a 14-minute monologue, the lone character is a mouth. Amid the vast darkness of a theater, that small lit mouth, relentless in its refusal to speak of a self in the first person, seems almost lost, a fierce flickering flame against the night. In Neil Jordan’s film, by contrast, the mouth of Julianne Moore fills the frame: projected onto a movie screen, the giant mouth could appear grotesque, but seen on television floating in a dark room, it lets us concentrate on the very act of speaking. Shot in one continuous take, the film nonetheless brings up another problem inherent to the form, in that theater is a three-dimensional environment, whereas film is really two; by cutting among five different angles, with no clear logic other than to create an impression of space, Jordan’s camera feels more restless instead, as if he didn’t trust us to just watch the play unfolding.

Throughout these films, a central element of theater is curiously missing, and to great effect: there is no stage. Rather, we are right there where the play is happening---in the room with Hamm and Clov in Endgame, beside Winnie in her mound in Happy Days. How we dwell with Beckett’s characters, by what rhythm we view them and receive their words, becomes the director’s prerogative more than ever. The subtle liberties taken by Anthony Minghella in Play are of a piece with Beckett’s own poetry, extending the dynamics to intensify the spatial and emotional depth. A man, his wife, and his mistress appear side by side, trapped in urns from the neck down, condemned to repeat the details of their affair when the focus lands, each in turn, on their mud-crusted faces. Where Beckett called for a single inquisitorial spotlight to animate the speakers back and forth, Minghella swoops in with his camera like a trigger to the action, layering the takes to suggest the perpetuity of their confessions. Moreover, on stage there are but three urns; the film repeats the image, so that beyond the actors---Alan Rickman, Kristin Scott-Thomas, Juliette Stephenson---a whole desolate landscape is revealed, filled with urn-bound figures.

One of the benefits of this project, which grew out of the original productions at the Gate Theatre in Dublin, is that it introduces a number of seasoned actors---and some emerging Irish directors (Conor McPherson, John Crowley, Kieron J. Walsh)---to Beckett’s work. But while many of the bigger roles are performed by well-known actors, these are not star turns. John Hurt, as directed by Atom Egoyan in Krapp’s Last Tape, is appropriately craggy and crotchety, and seems genuinely pained listening to the tape of his younger self. In Ohio Impromptu, Jeremy Irons brings a mournful, hollow-eyed weariness to the brief tale of loss and memory. Here, in response to Beckett’s wish that the Listener and Reader be “as alike in appearance as possible,” the film makes use of technical effects so that Irons can actually play both parts. With Catastrophe, a late work dedicated to Vaclav Havel, David Mamet draws on a full theatrical lineage in casting Harold Pinter as the manipulative Director, Rebecca Pidgeon as his enthusiastic assistant, and John Gielgud as the silent, suffering Protagonist.

While the directors generally show restraint in helping the plays achieve their proper resonance, the sets, of course, are paramount in establishing the visual relationships. Most of the films were shot in studio, but one remarkable departure is Happy Days, which Patricia Rozema shot on a volcanic hillside in Tenerife. Half-buried in her mound and dressed for a party, Rosaleen Linehan proves to be a splendid Winnie, who remains chipper and undaunted, even grateful for her life, despite exposure to the elements. That those elements are indeed real (the wind occasionally audible), confirmed by intermittent long shots where she becomes practically imperceptible amid the rugged landscape, makes her outlook even closer to miraculous.

Waiting for Godot, on the other hand, tender and droll as ever, was filmed in an abandoned creamery on a set that appears quite natural, with its rock-strewn expanse, its dirt road and bare tree, until at the end of Act One when the day quickly fades to night and an artificial moon rises into the sky. Common to most of the films, naturalistic sets fit Beckett’s texts surprisingly well, grounding them in the world we know and thus granting easier access to his finely sculpted writing. As it is, film encourages a more natural use of the voice, so that the actors don’t have to project as from a stage and may better control their delivery according to Beckett’s stringent requirements. In Endgame, such conditions aid and abet the performance nicely, where Michael Gambon and David Thewlis as Hamm and Clov, those modernist vaudevillians of despair, pivot and turn about the shabby room as they persist in trying to outwit each other.

Technology in the service of art, that is the ideal, yet how much waste along the way. Beckett on Film is a marvelous treasure, a box no bigger than a thick book, but of immeasurable depth. These production do not claim to be definitive versions. Rather, they are a fresh take, within the recent memory of their original creations, and taken together they serve as a milestone, a means to propel Beckett’s work into the future, toward new audiences. Like Krapp with his tapes, the format of the DVDs enables us to revisit the plays over and over, to rewind, jump ahead, compare. In a quiet room they speak to us, inside of us, ever curious and intangible voice to keep us company.

Beckett on Film

Dublin: Blue Angel Films, 2001

published in American Book Review (Normal, IL) 24:5 (July-Aug. 2003)_

Does the rigor of Samuel Beckett’s plays demand that they be appreciated only in a straight-back chair? Might an audience be allowed to get comfortable, even in the ease of one’s own home? And what happens when the theater hall shrinks to the size of a living room, the viewer divorced by a TV screen from the actors who are not there? What a sacrilege to film Beckett’s plays, now that he’s been dead a while and can no longer object, and yet what a terrific opportunity.

Beckett on Film is a laudable project, unique in the realm of theater. Produced in Ireland and shot during the year 2000, the four-DVD set presents all nineteen of Beckett’s stage plays filmed by nineteen directors who remain faithful to his texts while probing the resources of their medium. We know the arguments: theater is performed live, before a different public each night, and so the shifting nuances, the shared risk and mutual response. The theatrical space is like a temple, where the spirit must be conjured up anew, collectively. Film offers none of that; its magic is more mechanical, engineered by a particular syntax of the gaze. What, then, is gained by such an enterprise?

Most obviously, a sense of intimacy. But Beckett’s plays are already intimate, often featuring a single character and never more than three or four, with their deep subterranean river of consciousness giving rise to the voices. Film, however, brings the possibility of the close-up. In Not I, a 14-minute monologue, the lone character is a mouth. Amid the vast darkness of a theater, that small lit mouth, relentless in its refusal to speak of a self in the first person, seems almost lost, a fierce flickering flame against the night. In Neil Jordan’s film, by contrast, the mouth of Julianne Moore fills the frame: projected onto a movie screen, the giant mouth could appear grotesque, but seen on television floating in a dark room, it lets us concentrate on the very act of speaking. Shot in one continuous take, the film nonetheless brings up another problem inherent to the form, in that theater is a three-dimensional environment, whereas film is really two; by cutting among five different angles, with no clear logic other than to create an impression of space, Jordan’s camera feels more restless instead, as if he didn’t trust us to just watch the play unfolding.

Throughout these films, a central element of theater is curiously missing, and to great effect: there is no stage. Rather, we are right there where the play is happening---in the room with Hamm and Clov in Endgame, beside Winnie in her mound in Happy Days. How we dwell with Beckett’s characters, by what rhythm we view them and receive their words, becomes the director’s prerogative more than ever. The subtle liberties taken by Anthony Minghella in Play are of a piece with Beckett’s own poetry, extending the dynamics to intensify the spatial and emotional depth. A man, his wife, and his mistress appear side by side, trapped in urns from the neck down, condemned to repeat the details of their affair when the focus lands, each in turn, on their mud-crusted faces. Where Beckett called for a single inquisitorial spotlight to animate the speakers back and forth, Minghella swoops in with his camera like a trigger to the action, layering the takes to suggest the perpetuity of their confessions. Moreover, on stage there are but three urns; the film repeats the image, so that beyond the actors---Alan Rickman, Kristin Scott-Thomas, Juliette Stephenson---a whole desolate landscape is revealed, filled with urn-bound figures.

One of the benefits of this project, which grew out of the original productions at the Gate Theatre in Dublin, is that it introduces a number of seasoned actors---and some emerging Irish directors (Conor McPherson, John Crowley, Kieron J. Walsh)---to Beckett’s work. But while many of the bigger roles are performed by well-known actors, these are not star turns. John Hurt, as directed by Atom Egoyan in Krapp’s Last Tape, is appropriately craggy and crotchety, and seems genuinely pained listening to the tape of his younger self. In Ohio Impromptu, Jeremy Irons brings a mournful, hollow-eyed weariness to the brief tale of loss and memory. Here, in response to Beckett’s wish that the Listener and Reader be “as alike in appearance as possible,” the film makes use of technical effects so that Irons can actually play both parts. With Catastrophe, a late work dedicated to Vaclav Havel, David Mamet draws on a full theatrical lineage in casting Harold Pinter as the manipulative Director, Rebecca Pidgeon as his enthusiastic assistant, and John Gielgud as the silent, suffering Protagonist.

While the directors generally show restraint in helping the plays achieve their proper resonance, the sets, of course, are paramount in establishing the visual relationships. Most of the films were shot in studio, but one remarkable departure is Happy Days, which Patricia Rozema shot on a volcanic hillside in Tenerife. Half-buried in her mound and dressed for a party, Rosaleen Linehan proves to be a splendid Winnie, who remains chipper and undaunted, even grateful for her life, despite exposure to the elements. That those elements are indeed real (the wind occasionally audible), confirmed by intermittent long shots where she becomes practically imperceptible amid the rugged landscape, makes her outlook even closer to miraculous.

Waiting for Godot, on the other hand, tender and droll as ever, was filmed in an abandoned creamery on a set that appears quite natural, with its rock-strewn expanse, its dirt road and bare tree, until at the end of Act One when the day quickly fades to night and an artificial moon rises into the sky. Common to most of the films, naturalistic sets fit Beckett’s texts surprisingly well, grounding them in the world we know and thus granting easier access to his finely sculpted writing. As it is, film encourages a more natural use of the voice, so that the actors don’t have to project as from a stage and may better control their delivery according to Beckett’s stringent requirements. In Endgame, such conditions aid and abet the performance nicely, where Michael Gambon and David Thewlis as Hamm and Clov, those modernist vaudevillians of despair, pivot and turn about the shabby room as they persist in trying to outwit each other.

Technology in the service of art, that is the ideal, yet how much waste along the way. Beckett on Film is a marvelous treasure, a box no bigger than a thick book, but of immeasurable depth. These production do not claim to be definitive versions. Rather, they are a fresh take, within the recent memory of their original creations, and taken together they serve as a milestone, a means to propel Beckett’s work into the future, toward new audiences. Like Krapp with his tapes, the format of the DVDs enables us to revisit the plays over and over, to rewind, jump ahead, compare. In a quiet room they speak to us, inside of us, ever curious and intangible voice to keep us company.