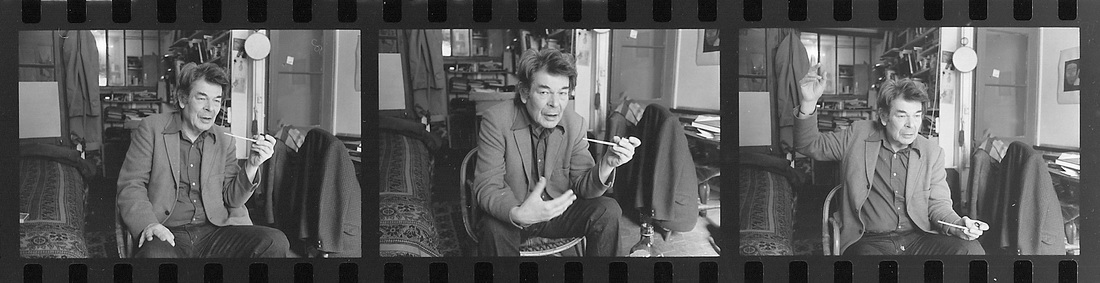

Roger Blin: Maverick of the Paris Theater

published in the International Herald Tribune (Paris), 13-14 June 1981

Some call Roger Blin a maverick; others, an innovator. He is humble and unassuming; scholars seem to pass him by, curious only about artists he has known. He is, to understate it, not rich. And he is a man to whom the modern theater owes a great deal of its power and vision.

Known as the director of Samuel Beckett's plays in French, Roger Blin, after more than 50 years as an actor-director in French avant-garde theater, is still little known outside France, except by theater people.

When Samuel Beckett's wife brought Waiting for Godot in the original French to him in 1949, Blin had already decided to follow his own path. Installed at Paris's Gaité-Montparnasse theater, he was directing his first production, The Ghost Sonata, by the Swedish playwright August Strindberg.

Blin responded to Beckett's work immediately. "I discovered Beckett in a way," Blin says. "When I read it, I said to myself, 'You must do this.' That it was important, I knew.

"It corresponded to something I was looking for, that wasn't at all part of the French world---even though it's written in French and there are jokes in French. Precisely because he loved to write in French, that helped him discover all sorts of things. Beckett seemed to me entirely new."

Blin persisted in trying to find a theater for the piece, but it was not until 1953 that he was able to mount the play at the new Théâtre Babylone, acting in it as well. The play caused a scandal, but it made people curious; both Blin and Beckett were launched.

Born and raised in the Paris area, Blin was a film critic in the 1920s for various newspapers and film journals, eventually becoming assistant to director Jean Renoir. The source of Blin's resolve to take up acting, though, is still evident: he stutters. "But never on stage," he pointed out during a recent conversation. "I couldn't talk, so I told myself, 'You should become an actor.' That's all, that's the only reason. So, having speech difficulties, I had as a goal to lie. The lie alone leads to theater."

In 1932, he joined the new revolutionary theater troupe Le Groupe Octobre, which practiced a sort of proletarian theater entertaining at Communist meetings in Paris. "Jacques Prévert provided the texts," Blin said. "On the one hand, I---the son of a petit bourgeois---had moral and political influences from Prévert. He cleaned me up a lot. And on the other, I was connected with Antonin Artaud in Montparnasse. They were my spiritual fathers."

But Blin never studied with anyone. "I was never interested in being anyone's student," he said. His first professional appearance on stage was in 1935, in Artaud's provocative Les Cenci, in which he portrayed a deaf-mute assassin. He also worked as Artaud's assistant.

Blin occasionally acted in films, including two by Marcel Carné, but became quickly locked into what he calls "village-idiot roles." He maintained his independence from theatrical companies and establishments, and in the late 1940s turned down an offer from Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud to join their new company.

After the shock and success of Godot, Blin and the actor Jean Martin asked Beckett to write something for them; the author came up with Endgame, which he dedicated to Blin. But Parisian theater managers were slow to recognize Beckett's importance; Endgame had to open in London.

Later, Beckett wanted Blin to act in the French production of Krapp's Last Tape, but Blin opted to direct it instead, because "I was afraid to be alone on the stage." He later performed it in a studio for Swiss television.

When Blin first brought Happy Days to Madeleine Renaud in 1962, "she was bursting with joy," Blin said. "It was a turning point in her life as an actress. She had played everything, but still she wanted to take a new turn."

Blin's production of Godot has been revived frequently, but when it was put on by the Comédie Française in 1978, it was only because "the actors were friends whom I like and who have a lot of talent," Blin said. "There is a lot of talent at the Comédie Française. All the same, I didn't like the place."

Seeking his actors according to the piece, Blin has never wanted a company of his own. "I never wanted to play the guru, to gather together 15 or so young people and pay them next to nothing. Because there are so many different things that I have put on." Always open to new ideas, he has never gone after commercial success in a city that loves boulevard comedies.

Highly respected by the critics at last, he has often introduced playwrights new to French audiences. His 1961 production of Harold Pinter's The Caretaker and his 1976 production of Boesman and Lena, by South African anti-apartheid writer Athol Fugard, are such cases.

Yet Blin is no idealist. He seeks always what is alive in people. "Beckett interested me in himself, in what his work was, to the extent that it demolished three-quarters of contemporary theater," Blin said. "And so it also has a combat value for me.

"I've always had this idea of combat. In staging Jean Genet's The Blacks, I certainly intended to anger the whites. In staging his The Screens, I meant to anger the colonialists. But neither have I mounted plays simply because of an ideology. It must have an inner value."

Blin's production of The Screens in 1966, in a masterful staging for the Odéon's Théâtre de France while it was under Jean-Louis Barrault's direction, provoked such scandal among right-wing factions that the theater became a political battleground during the run, and is said to have been the cause of Barrault's dismissal in 1968.

But as a director, Blin has "a position of active humility," he said. "When I have a beautiful text, I really try to enter into it and to serve the author, to the point where I discover that the author has not seen certain things in it. But I'm not at all looking to translate it into a personal fantasy. I put my fantasies elsewhere."

In theater today, Blin sees two particular trends, both of which, he is confident, will run their course. "On the one hand, there are troupes who have a lot of money and put on superproductions, without really occupying themselves with the play and the actors. On the other, there is a sort of return to naturalism, that arrives at an absolute platitude, under pretext of truth.

"The poetry of theater," Blin asserts, "is not metaphoric. It is in the rhythm." He has devoted much time and thought to the possibilities of theatrical expression, and the piles of scripts spilling everywhere in his dimly lit apartment bear witness to Roger Blin's effect.

Facing his younger self in Artaud's framed 1946 portrait, Blin said, "Absolute realism in theater doesn't exist, because there is a fourth wall that isn't there. So, why? Why take actors, why not sooner take some people and make them play it? Why have the end?"