Paris spring 1980: Three Jazz Concerts

published in Coda (Toronto) 174 (August 1980): 35-36

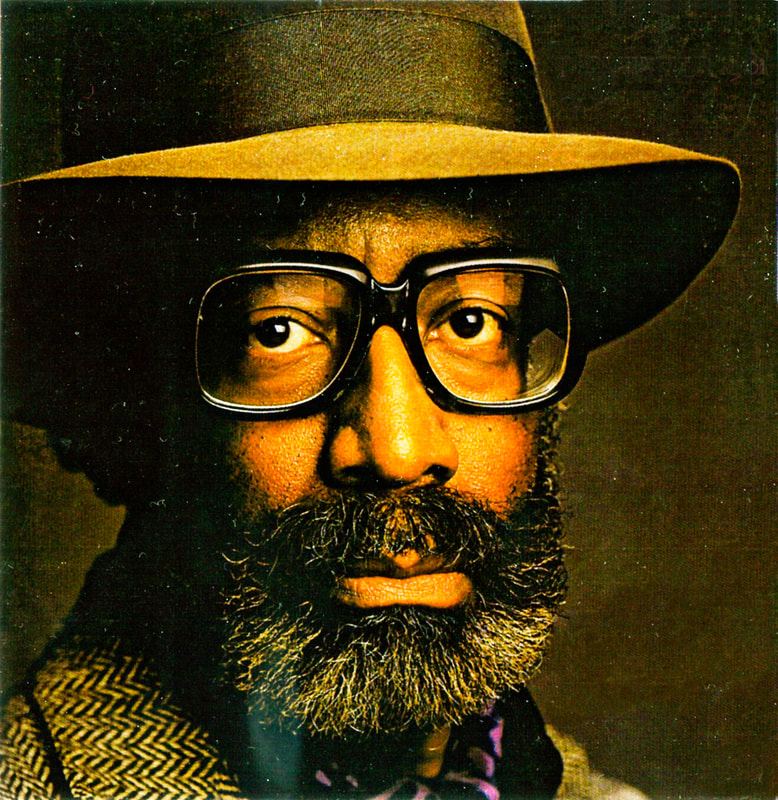

Bill Dixon

Chapelle des Lombards, 18-24 June 1980

Bill Dixon – trumpet, piano; Steve Morrissey – tenor saxophone; Alfred Brooks, Steve Haynes, Earl Cross – trumpet; Kent Carter, Alan Silva – bass; Oliver Johnson – drums.

Bill Dixon does something unusual: he talks between pieces, to the audience, to his musicians. He pierces the unapproachable barriers between listeners and performers by telling something of what he’s after with a certain piece, by relating anecdotes that offer jazz as a personal history as well as an art (how he’ll always remember, long ago in Massachusetts, Rex Stewart’s band call on the cornet, an F above high C, and all the Ellington musicians would have to drop what they were doing, or speaking lovely to, and get back on the stand). And too, by telling the musicians what he wants, and after, asking them how it felt that time.

But Bill Dixon is also unusual in other ways. Each piece is a different exploration, as important for each musician, no matter the extent of their experience with Dixon’s compositions, as for Dixon himself. He wants to hear how things can sound, how they may differ with the setting and the space. With each piece, the musicians are combined and recombined in varying proportions, demonstrating on a small scale the range of what is possible. He’s not interested in putting on a show, he just wants to work with his musicians and share with the audience something of that work as well as the beauty; when he decides to do a free improvisation piece, we hear the rough framework he lays out ahead of time.

Listening to Bill Dixon is a lesson as much as an experience. He knows something and he’s willing to let you in on it. The opportunity should not be missed.

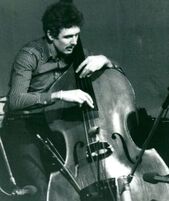

Maarten van Regteren Altena

Institut Neerlandais, 11 May 1980

Solo bass

Amid a concourse of old high-ceilinged drawing rooms, the small square stage faced out in two directions at right angles to each other, and the audiences in the two rooms could not see each other. Only the stage, occupied by the bassist and his objects. He started easily, bowing notes and small phrases on up into the high registers, slowly working them into a momentum where anything could happen. In two improvised solos of thirty to forty minutes in length, Maarten van Regteren Altena employed a maximum of methods and devices to once again demonstrate the possible extent of the language of the bass. Bowing more often than not, his lines were quick and quick to change towards other landscapes. As other soloists have done, Steve Lacy and Leroy Jenkins among them, he turned on a tape recorder and played off of the pre-recorded music, though the tape itself was a constant repetition of several bars of an older classical music, also on bass. At first, while the taped music played, he took out a cigar from a wooden cigar box, lit it and as he walked around the stage, at intervals he would bow some squeaks from the box itself while exhaling corresponding breaths of cigar smoke. As has been indicative of his improvised solos, he was repeatedly tuning and retuning his instrument and playing off of the altered possibilities. He played with two extra bridges, spaced along the fingerboard, and largely explored their new harmonics. He played against a metronome, almost mocking its strictness, and not long after kicked it silent. He used the wood of the bow, and early in the second piece bowed over the strings with a circular motion, turning his bass while walking himself in a circle, first counterclockwise, then clockwise. He wedged the bow in between the strings, across them, and slapped it, the bow rocking by itself sounding all the strings. That allowed him a moment’s rest and then he took his other bow and played over it. At times his hoots and cries underlined his phrases, sometimes they anticipated them. At one point, silence, he jumped up and down on the stage, as if limbering up, but beyond that was the ample rhythmic sound that his jumping produced. A curious entertainment for an audience where only a small amount of people knew what to expect, on a weekend of generally more conventional jazz at the Institut Neerlandais. It is difficult to imagine Altena being able to play as free in even a duo setting.

Mike Zwerin Quartet

American Center, 28 May 1980

Mike Zwerin – trombone, bass trumpet, piano; Jean Cohen – tenor and soprano saxophones; Beb Guerin – bass; Bernard Gauthier – drums.

What was originally billed as Mike Zwerin’s trio, Not Much Noise, was in the final weeks changed to a quartet date with a different group of musicians. As Zwerin is a fine player, it is interesting to hear him in any context. Comparisons are unimportant, for he is thoroughly educated in the range of modern trombone styles, and he places his sounds intelligently. Most importantly, he seemed to be enjoying himself.

The classically balanced quartet, a departure from Zwerin’s regular, more explorative trio, played a straight-ahead mixture of mostly post-bop compositions which included vintage Mingus and Coltrane tunes, Carla Bley’s “Sing Me Softly of the Blues,” and Ornette Coleman’s “Blues Connotation.” Particularly in those tunes, a respect for the ensemble sound of each of the original composers was evident, while the group maintained sight of its own directions with the pieces. So that, as to Zwerin himself, on the Mingus tune one was reminded at times of the bright ever-responding sound of Jimmy Knepper, in the ensemble passages especially, while on the Carla Bley piece there was the clear memory of Roswell Rudd’s work on some of her more tender compositions. Yet, as with the works themselves, the styles were but fond reference points for further voicings.

Jean Cohen’s tenor playing (which he stayed with after soprano on the Mingus piece) was most often strongly reminiscent of Archie Shepp’s intonations, but as such it could be lovely. His lines would begin thoughtful and lyrical in the lower registers, with a full throaty sound, and soon, as if possessed each time, they would strain into the high notes, with a sort of measured passion. Beb Guerin’s bass work filled the spaces, playing off of the main lines, as was particularly effective in the trio rendition of “All the Things You Are.” And though Zwerin usually employs no drummer these days, Bernard Gauthier was neither overly dominating nor did he hold the others back; his playing worked cohesively, though his solos were not especially inventive (this was somewhat the case with Guerin) until later in the evening, on “Meeting Point” and the encore piece, where he displayed a range of colors not hinted at earlier. For the last two numbers, Eric Watson’s often ethereal piano added a further dimension to the more contemporary pieces.

One focuses on the compositions performed because the group faced each piece in a fresh way as varied as the music. And too, because the leader knows the music intimately and has loved it for a long time. They meant what they played and they liked being there.