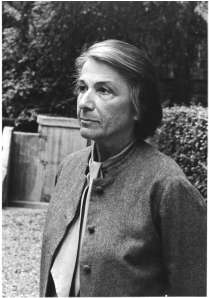

Nathalie Sarraute

Portions of this interview were first published in Exquisite Corpse (Baton Rouge) 6:10-12 (Oct.-Dec. 1988); the entire text appeared in The Paris Review (New York) 114 (Spring 1990), and later in Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (Iowa, 1991), now out of print.

Nathalie Sarraute (1900-1999) was eighty-three when she first published a bestseller, Childhood (1983). Unlike her previous books, it treated autobiographical events. In the book, memories from her Russian and French childhood emerge from a word or a gesture recalled, burn brightly for a moment, and fade. Quietly the mosaic takes shape in her compassionate regard for the parents whose early divorce divided her love.

Born in Ivanovo, near Moscow, Sarraute made a lifetime of seeing inside being human. Her first book, Tropisms (1939), a collection of brief texts, marked a fresh direction in French literature and established her as the first of what came to be known as the nouveau roman group of writers. She described tropisms as the “interior movements that precede and prepare our words and actions, at the limits of our consciousness.” They happen in an instant, and apprehending them in the rush of human interactions demands painstaking attention. Tropisms became the key to all her subsequent work.

Highly respected in France, Sarraute has been translated into twenty-four languages; her eight novels and other books are all available in English. Since the 1960s she traveled often, invited to universities around the world. Her husband, whom she met in law school, always accompanied her. She visited the United States every few years, and was last in New York in September 1986, for the American premiere of her play Over Nothing at All. In the fall of 1990 she was invited to visit the house where she was born in Ivanovo.

For decades, Sarraute went every morning to write at the same neighborhood cafe in Paris. The following interview took place on two cold January afternoons in 1987, at her home in the sixteenth arrondissement near the Musée d’Art Moderne.

In your books you have a very fine ear, for the interior voices as well as for the development of the text. Another domain of listening, of course, is music. Do you listen much to music?

I like music a lot, almost too much. Sometimes so much even that it gives me a sort of feeling of anguish. But I haven’t listened a lot, partly because of that. It’s quite curious, the effect it has on me. And precisely in the works I prefer, it’s a sort of anguish that I never have from painting, which always gives me a feeling of eternity, security, peace. Of immobility. I love painting a great deal. Music at times reaches something that is almost superhuman, divine. One listens to Mozart and says, It’s not possible that a human being did that.

Were you ever tempted to write another sort of literature, such as the fantastic?

Not at all. Because each instant of the real world is so fantastic in itself, with all that’s happening inside it, that it’s all I want.

At the time of your first book, Tropisms, what was your rapport with the literary world?

I didn’t know anyone, not a single writer. I didn’t meet Sartre until the war. After the Liberation, he wrote the preface for my first novel, Portrait of a Man Unknown (1947).

How did you arrive at the form of those first short texts?

The first one came out just as it is in the book. I felt it like that. Some of the others I worked on a lot.

And why did you choose the name Tropisms?

It was a term that was in the air, it came from the sciences, from biology, botany. I thought it fit the interior movement that I wanted to show. So when I had to come up with a title in order to show it to publishers, I took that.

How did you know what they were at the time, these tropisms? How did you know when you’d found one?

I didn’t always know, I might discover it in the writing. I didn’t try to define them, they just came out like that.

The tropisms often seem to work through a poetic sensibility.

I’ve always thought that there is no border, no separation, between poetry and prose. Michaux, is he prose or poetry? Or Francis Ponge? It’s written in prose, and yet it’s poetry, because it’s the sensation that is carried across by way of the language.

With the tropisms, did you feel that it was fiction? Did you wonder what to call it?

I didn’t ask myself such questions, really. I knew it seemed impossible to me to write in the traditional forms. They seemed to have no access to what we experienced. If we enclosed that in characters, personalities, a plot, we were overlooking everything that our senses were perceiving, which is what interested me. One had to take hold of the instant, by enlarging it, developing it. That’s what I tried to do in Tropisms.

Did you sense at the time that was the direction your work would go?

I felt that a path was opening before me, and which excited me. As if I’d found my own terrain, upon which I could move forward, where no one had gone prior to me. Where I was in charge.

Were you already wondering how to use that in other contexts such as a novel?

Not at all. I thought only of writing short texts like that. I couldn’t imagine it possible to write a long novel. And after, it was so difficult finding these texts, each time it was like starting a new book all over again, that I told myself perhaps it would be interesting to take two semblances of characters who were entirely commonplace as in Balzac, a miser and his daughter, and to show all these tropisms that develop inside of them. That’s how I wrote Portrait of a Man Unknown.

In effect, one could say that all or most tropisms we might find in people could also be found in a single person.

Absolutely. I’m convinced that everyone has it all in himself, at that level. On the exterior level of action, I don’t for a minute think that Hitler is like Joan of Arc. But I think that at that deep level of tropisms, Hitler or Stalin must have experienced the same tropisms as anyone else.

The tropisms would seem to enter the domain of the social sciences as well.

Yes. I’ve become more accessible, besides. It used to be entirely closed to people. For a long time people didn’t get inside there, they couldn’t manage to really penetrate these books.

Why do you think that is?

Because it’s difficult. Because I plunge in directly, without giving any reference points. One doesn’t know where one is, nor who is who. I speak right away of the essential things, and that’s very difficult. In addition, people have the habit of looking for the framework of the traditional novel—characters, plots—and they don’t find any, they’re lost.

That brings up the question of how to read these books. You do without plot, for example.

There is a plot, if you like, but it’s not the usual plot. It is the plot made up of these movements between human beings. If one takes an interest in what I do, one follows a sort of movement of dramatic actions which takes place at the level of the tropisms and of the dialogue. It’s a different dramatic action than that of the traditional novel.

You’ve said that you prefer a relatively continuous reading of your books. But all reading is a somewhat fragmentary experience. With a traditional novel, when one picks it up again to continue reading, there are the characters and the plot to situate oneself, where one left off. In your books, do you see other ways of keeping track of where one was?

I don’t know. I don’t know how one reads it. I can’t put myself in the reader’s place, to know what he’s looking for, what he sees. I have no idea. I never think of him when I’m writing. Otherwise, I’d be writing things that suit him and please him. And for years he didn’t like it, he wasn’t interested.

Even after several books you weren’t discouraged?

No, not at all. I was always supported, all the same, from the start. With Portrait of a Man Unknown, I was supported by Sartre. At the time, Sartre was the only person who was doing something about literature, he had a review. My husband as well was tremendously supportive, from the very start. He was a marvelous reader for me, he always encouraged me a great deal. That was a lot. It suffices to have one reader, who realizes what you want to do. So, it was a great solitude, if you like, but deep down inside it wasn’t solitude. Sartre was impassioned by Portrait of a Man Unknown. So, that was very encouraging. Then when Martereau (1953) was done, Marcel Arland was very excited and had it published with Gallimard. He was editing the Nouvelle Revue Française at the time. I always had a few enthusiastic readers. When Tropisms came out, I received an enthusiastic letter from Max Jacob, who at the time was very admired as a poet. I can’t say it was a total solitude.

Did Sartre or others try to claim you as an existentialist?

No, not at all. He had published the beginning of Portrait of a Man Unknown in his review, Les Temps Modernes, and then he wrote the preface because he wanted to. And he told me, “Above all, they shouldn’t think it’s a novel that was influenced by existentialism.” Which couldn’t be the case, because Tropisms came out almost the same time as Nausea.

It was rather another existentialism.

He was entirely conscious of that. And very honestly he said, “It is existence itself.”

You’ve said that it was during your law studies that you became attracted to the spoken language, which became your written language in effect. How did that opening come about?

When I was working in law I didn’t practice much, but I prepared probate conferences, which were literary; one said them, it’s a spoken style. I’d worked those conferences a lot, they went well. And so, I think that tore me away from the written language, which I’d always been subjected to since childhood by the very strict French homework. It gave me a kind of impetus toward the freer language, which is spoken French. It did play some role.

The language seems lighter, there’s a greater facility in the flow of the writing.

That facility demands an enormous amount of work. What a job!

Did you look for models elsewhere?

No, I never thought of comparisons. They were things that I felt spontaneously, really. It wasn’t taken from literature but from life rather.

Do you imagine other ways of writing about the tropisms?

No, because for me form and content are inseparable. So, that would be something else. If the form is different, it will be another sensation. And for this genre of sensation, it’s the only form.

Do you feel there are other writers who have found certain lessons in the domain of tropisms?

I don’t feel I have any imitators. I think it’s a domain that is too much my own.

Would it be possible to use the tropisms in a more traditional novel?

I don’t see how. What interest would there be? Because in a more traditional novel, one shows characters, with personality traits, while the tropisms are entirely minute things that take place in a few instants inside of anybody at all. What could that bring to the description of a character? On the contrary.

As if at the moment of the tropisms, the character vanishes.

He disintegrates, before the extraordinary complexity of the tropisms inside of him.

Which is what happens in Martereau.

Martereau disintegrates. And in Portrait of a Man Unknown, the old man, the father, becomes so complex that the one who’s looking to see inside of him abandons his quest, and at that moment we end up with a character out of the traditional novel, who ruins everything. In Martereau, it’s the character out of the traditional novel who disintegrates at the end.

Yet in The Planetarium (1959), it seems that more than ever you’re using traditional characters.

On purpose. Since they are semblances, it’s called The Planetarium, and is made up of false stars, in imitation of the real sky. We are always for each other a star, like those we see in a planetarium, diminished, reduced. So, they see each other as characters, but behind these characters that they see, that they name, there is the whole infinite world of the tropisms, which I tried to show in there.

Considering the interior nature of your writing, has it sometimes been difficult to remain at such depths?

No, what is difficult is being on the surface. One gets bored there. There are a lot of great and admirable models who block your way. And once I rise to the surface, to do something on the surface, it’s easy, but it’s very tedious and disappointing.

In Portrait of a Man Unknown the specialist consulted by the narrator tells him: “Beware of this taste for introversion, for daydreaming in the void, which is nothing but an escape before the effort.”

Yes, because he feels that he is marginal, he feels that he’s not normal. It’s entirely ironic. He goes to see a psychiatrist who tries to put him on the right path. In my books there are always these normal people who don’t understand these tropisms, who don’t feel them.

With Portrait of a Man Unknown, had you decided to avoid using characters?

No, on the contrary, I wanted to take semblances of characters, types, the miser for example, like Père Grandet, and then to try to see what really happens in him, which is of an enormous complexity. It is so complex that the character who is searching him out abandons the search, he can’t go on anymore. And at that moment the character from the traditional novel is introduced, who has a name, a profession, who marries the daughter, etcetera. We fall back into the traditional novel and dialogue.

While you were writing this book, did you know how it was going to end?

No, I found the ending when I got to the end. Usually, it develops like that, like an organism that develops. Often I don’t see the ending at all, it comes out of the book on its own.

You’ve said that with the novels you wrote the first draft directly from beginning to end.

At first. I always have to make a beginning that’s entirely finished, the first few pages must be fixed in place. Like a spring-board, that I take off from, I don’t rework it any further. I work on it a lot, and then it’s finished. But after that, I wrote from one end to the other. I used to work like that, not now. I wrote from one end to the other, in a form that was sometimes a bit rough, I found the general movements, and then I rewrote the whole thing. For a while now, though, I’m afraid of waiting two or three years like that before starting over. So, I write gradually, I finish each passage as I go along. I changed my system about six years ago, since The Use of Speech and Childhood.

In Martereau the narrator speaks of the importance of words, of what they hide. For Martereau, who is rather a traditional novelistic character, words are “hard and solid objects, of a single flow.” One would say that in your books you feel a certain seduction of words.

Yes, it’s words that interest me. Inevitably. It’s the very substance of my work. As a painter is interested in color and form.

Some say the most important problem in the novel is time. In your book of essays, The Age of Suspicion (1956), you said that “the time of the tropisms was no longer that of real life but of an immeasurably expanded present.” In the novels time is surely complicated then.

There are always instants. It takes place in the present finally. I’m concerned with these interior movements, I’m not concerned with time.

Is that because you often do without plot?

Completely. It has to do with a dramatic development of these interior movements, that’s the time. There is no exterior reference.

So then it’s a sort of freedom from time.

Time is absent, if you like.

How was it you realized you could do without plot in the first place?

The question never posed itself for me. Given what I was interested in, plot didn’t enter into it. I was involved as with a poem, one writes a poem and isn’t concerned with such matters as plot. It was a free territory, there were no pre-established categories that I was obliged to enter into.

In effect there are quite a few correspondences with poetry in your work.

I hope so. There was a book by an Australian, on my novel Between Life and Death, who called it a “poetry of discourse.” He called it a novelistic poetry. Not a poetic novel, because that’s been done.

Have you read a lot of poetry?

Not especially. I’ve read some. You know, outside reading has not played a big role in my work.

Well, what sort of reading was important for you?

What really turned me around was reading Proust, it was a revelation of a whole world, and reading Joyce too. The interior monologue of Joyce. They’re things without which I wouldn’t have written as I do. We always start from our predecessors. If I’d written in the eighteenth century, I wouldn’t have written like that. There had to be writers like that before me, who opened up such realms.

Were you fairly young when you read them?

Yes. I read Proust when I was twenty-four, and Joyce at twenty-six.

In your essay, “From Dostoyevsky to Kafka,” you say that Kafka “traced a long straight path, a single direction and he went all the way.” Don’t you think there is any continuation beyond him?

I don’t think so. They’ve sought to imitate him a lot, at a certain moment it was fashionable to write like Kafka, but in my opinion that didn’t lead anywhere.

It seems, however, that there is more than a single direction in Kafka. There are various levels, that of the story, of the way he tells it, but there is also the poetic dimension, the parables.

I wasn’t concerned with all that. It was a period when there was a hate, a mistrust, of “psychology.” People were divided between those who were for Dostoyevsky, and those for Kafka, that is against psychology. At the time, I didn’t know Kafka’s work at all. I read Kafka very late, after the Liberation. I didn’t like “The Metamorphosis,” I only liked The Trial and The Castle. So, they were opposing Kafka with Dostoyevsky; in Kafka they said there was emptiness, no psychology. I wanted to show that even in Kafka there was psychology, we can’t do without it. It was a psychology pushed to the ultimate despair, the total absence of human contact. I was never concerned with a full analysis of Kafka, I’m not a critic. And then Kafka is not an author who influenced me. I must have been about forty-five by the time I read him.

The central concern of the essay was with the psychological.

That’s right. I wanted to defend this conscience that was so despised, which Kafka supposedly didn’t have. I found that he had a lot of it, and that every writer worthy of that name cannot do without the internal life.

Elsewhere in that essay you made a distinction between the characters in the work of those two writers, saying that “while the quest of Dostoyevsky’s characters leads them to seek a sort of interpenetration, a total and always possible fusion of souls, with Kafka’s heroes it has to do with simply becoming, ‘in the eyes of those people who regard them with such scorn,’ not perhaps their friend but finally their co-citizen.” Isn’t this distinction a condition of the Christian and Jewish contexts of the two writers?

I never got involved with that question, because I think that what’s interesting there is to step outside of those contexts and to see the human being in depth. Kafka’s universe has become a part of our own universe, and the Jewish question doesn’t intervene at all. Moreover, neither in The Castle nor in The Trial does he speak of it. We have the right to deal with that if the author himself puts it in his work. But if it remains outside, I don’t see why a Christian couldn’t read Kafka’s The Trial or The Castle in the same way as a Jew. It addresses itself to everyone, that’s why it’s a great work.

I was thinking more of their cultural formations.

I’m not concerned with that. I’m not a critic. I’m concerned with what touches me directly as a writer.

In one of the essays you also quote Katherine Mansfield’s phrase, “this terrible desire to establish contact.” But once a person takes off on a more experimental path, like yours for example, what becomes of that need? Were you yourself thinking along such lines?

No, when I work I never ever define from the outside, I don’t qualify what I’m doing. I’m looking to see what is felt, what do we feel. I don’t know what it is, and that’s why it interests me, precisely because I don’t know exactly what it is. Those were theoretical essays, they have nothing to do with my work when I write. I don’t put myself at that distance, I’m entirely inside.

In the essay “The Age of Suspicion,” you said that the novel “has become the place of the reciprocal mistrust” of the reader and the writer. Do you think that with the contemporary novel that mistrust has gotten deeper, more serious?

That’s an entirely personal question. I’m not terribly interested, except when I’m reading Agatha Christie or novels that carry me away, in the personalities of the characters nor in the plot. When I see a novel written in that form, it might amuse me, it can be slices of life or descriptions of manners, but I can’t say that it interests me as a writer. There are those who like that, obviously, people do continue to write in that way.

Do you feel, for example, that the contemporary novel has become more conservative?

There was a period when we fell back joyfully into the tradition. There was a strong academic tendency, in the theater as well, everywhere. And I think all the same we’re getting out of that once again. The admiration for academicism is declining.

If there is such a thing as an evolution of the novel, do you see it as a one-way street?

I’m not a critic, you know. I only read what interests me, what passes my way. I don’t have any opinion on the current evolution of literature. I think that the writers who were grouped under the term nouveau roman have all continued to write each in his way, works which have remained alive for the most part.

On various occasions, especially in your essay on Flaubert, you’ve spoken about dispensing with the old accessories such as plot and characters. But are those old accessories so useless as that, are there no truths to be reached with them?

One reaches certain truths, but truths that are already known. At a level that’s already known. One can describe the Soviet reality in Tolstoy’s manner, but one will never manage to penetrate it further than Tolstoy did with the aristocratic society that he described. It will remain at the same level of the psyche as Anna Karenina or Prince Bolkonsky. If you use the form that Tolstoy used. If you employ the form of Dostoyevsky, you will arrive at another level, which will always be Dostoyevsky’s level, whatever the society you describe. That’s my idea. If you want to penetrate further, you must abandon both of them and go look for something else. Form and content are the same thing. If you take a certain form, you attain a certain content with that form, not any other.

But even so, the form is something you’ve discovered each time.

Each time it has to find its form. It’s the sensation that impels the form.

In your essay “Conversation and Sub-conversation” you speak of certain ideas that Virginia Woolf and others had about the psychological novel, saying that perhaps it hasn’t yielded as much as they had hoped at the time.

That was meant ironically. I agreed with her. I don’t really like the word “psychological,” which has been used a lot, because that makes one think of traditional psychology, the analysis of feelings. But I would say that the universe of the psyche is limitless, it’s infinite. So, each writer can find there what he would like. It’s a universe as immense as we all are, and there are writers yet who are going to discover huge areas of the life of the psyche, that exist but which we haven’t brought to light.

In the same essay you also speak of the American example, as a reason to look beyond the psychological. Who were you thinking of, besides Faulkner?

The behaviorists, they were completely against that. Steinbeck, Caldwell, that wasn’t psychological at all. It was because of them that psychology was despised. It had a big influence, besides, on people like Camus, with The Stranger. It was fashionable at the time to say that there was no conscience, that it held no interest.

In “Conversation and Sub-conversation,” you particularly discuss the problem of how to write dialogues now, so that the sub-conversation may be heard. How did you arrive at your manner of reaching all those levels at once, in the way you write dialogue? Was it by a lot of experimenting?

No. That comes uniquely from intuition, it represents a big job of searching, in order to reconstitute all these interior movements. To relive it. To expand it, to show it in slow motion. Because it is very fleeting. It gets erased very quickly. And it’s very difficult to get ahold of.

You’ve written that the traditional methods of writing dialogue couldn’t work anymore.

Not for me. Because I would have to put myself at too much of a distance from the consciousness in which I dwell. I’m immersed right inside, and I try to execute the interior movements that are produced in that consciousness. And if I say, “said Henri” or “responded Jean,” I become someone who is showing the character from outside.

One of the things that marks your writing is the punctuation, which you work very carefully.

In the last few books there are a lot of ellipses; there were less of them before. Because I find that it prevents one from reading these movements, which are very quick and suspended, without breathing. There is need for a certain breathing when one reads it, and the ellipses create this breathing. They help in the rhythm of the sentence. It gives the sentence more flexibility.

Let’s talk about your theater work. Why did you start writing plays?

It was simply a request by the radio in Stuttgart. A young German, Werner Spiess, came to see me for the radio in Stuttgart, he asked me to write a radio play. That was in ‘64. He wanted something new, in a style that wouldn’t be like the usual style; it didn’t matter if it were difficult even. I started by refusing. He returned a second time, and I refused again. And then I thought about it one day. I told myself that perhaps all the same I could write a radio play, that it would be entirely a matter of the dialogue. I hadn’t thought I would be able to do it because for me the dialogues are prepared by the sub-conversation, the pre-dialogue. The dialogue only skims the surface of the sub-conversation. So, I decided everything will be in the dialogue, what is in the pre-dialogue will be in the dialogue. They later said my plays, in relation to my novels, were like a glove turned inside out. Everything that is inside, is now on the outside.

Which play was that?

First it was Silence, then The Lie, then the four other plays. They were always performed first for foreign radio.

That’s why you put hardly any directions in the text, because they were written for the radio.

That’s right, because they’re not written for the stage. There’s only one where I was thinking of the stage, that was It Is There. And still, not a lot. Above all, I hear the conversations and the voices, and I don’t see at all the theatrical space, the actors. All that is the job of the director. Which is a very interesting job, because everything remains to be done.

Have you attended rehearsals much?

Yes, I’ve attended rehearsals. First, with Jean-Louis Barrault, then with Claude Régy, then with Simone Benmussa. I don’t have a lot to say, except for the intonations, but not for the actors’ movements. That’s the director’s job.

Were all the plays requests like the first one?

It was always for the radio, always the same person who asked me. Then, after the radio in Stuttgart didn’t do difficult plays anymore, it was the radio in Cologne. And French radio too. Each time after having finished a novel, I rather liked writing a radio play. It distracted me, it gave me a bit of a change.

Did you have much experience of the theater apart from your plays?

I liked going to the theater, of course. I was quite impressed by Six Characters in Search of an Author by Pirandello, and The Dance of Death by Strindberg. Those two plays deeply impressed me.

You’ve said that your plays are like a continuation of your novels. What has the theater brought you for the writing of your novels?

Absolutely nothing. It has no relation whatsoever.

Are there voices in the modern theater that have particularly interested you?

No, not so much. Some of Pinter’s plays I’ve quite liked. Where he touches on things that interest me.

Has the experience of writing changed much for you since you were young? Do you have different habits?

I don’t feel that it’s changed. I think we always have the same difficulties with each new book; there is no acquiring of experience. Each new book is entirely another realm, in which one must try to find its form and its sensations, and the difficulties are the same as at the start. I see no progression. There is no technical experience gathered for me.

Was writing much different for you when your children were young?

No. I started to write when the third daughter wasn’t yet born, the two others were little; that played no role. I always had enough time for myself. You know, I don’t believe that women of the bourgeoisie can pretend they can’t write because they have children. That’s absurd. Claudel was the French ambassador in Washington and wrote an immense body of work; he never ceased to be ambassador and all that that represents. So, when you’ve got someone to take care of the children, and after when they go to school, it’s impossible not to find two or three hours in the day to work. It’s very different for a working-class woman, or for a working-class man, it’s the same problem. Not entirely the same, because the woman has still more work to do than the man. But there I understand completely that it’s impossible. One can’t speak like that of women from the intellectual milieu, which is always a bourgeois milieu. Especially before, since now it’s become more difficult, but before one found whatever one wanted for taking care of the children. There was no problem as far as that was concerned.

Considering the interior quality of your writing, do you see the fact of being a woman as giving you any special access to such a state? As if that predisposed you toward the interior rather than out toward action in the world.

No, I don’t think so at all. I don’t think that Proust or Henry James or even Joyce were turned elsewhere than toward the inside. It’s a question of the writer’s temperament.

Do you see any sort of difference between women’s writing and that of men?

No, I don’t see any. I don’t feel that Emily Brontë is a woman’s writing, among women who truly wrote well. I don’t see the difference. One says first of all, “That’s what it is to be a woman,” and then after one decides that is feminine. Henry James was always working in the minute details, in his lacework; or Proust, much more still than most women. I think that if women like Emily Brontë wanted to keep a pseudonym, they were entirely right. One cannot find a manner of writing upon which it would be possible to stick the label of feminine or masculine; it’s writing pure and simple, an admirable writing, that’s all. There are subjects in writing that are very feminine, which are lived, the women who write on feminine subjects like maternity, that’s completely different.

Let’s talk about cigarettes. Have you always been a smoker?

Alas! I shouldn’t smoke, but I don’t smoke a lot. Six or seven cigarettes a day. That’s still too much. I have a very bad habit. So, in order not to smoke, I’ve taken to holding the cigarette in my mouth while I work. I don’t light it. That gives me the same effect. Because I forget. I feel something and I forget if it’s lit. Since I smoke very weak cigarettes, and I don’t swallow the smoke, I have just as much the impression of smoking even if it’s not for real.

As if it enters into the game, in effect.

That’s right. It’s a gesture, something one feels.

Could we speak about the conception of some of your books? The Golden Fruits (1963), for example, did that come out of an experience with the literary world?

Not at all. I take no part in the literary world, I’ve never gone to the literary cocktail parties. It has to do with an inner experience. It has to do with a kind of terrorism around a work of art that is lauded to the skies and which we cannot approach. Where there is a sort of curtain of stipulated opinions that separates you from that work. Either we adore it or else we detest it, it’s impossible to approach it; above all in the Parisian milieu, even without going to the cocktail parties, even in the press, there reigns a kind of terrorism of general adulation, and you don’t have the right to approach it and have a contrary opinion. And then it falls; at that moment you no longer have the right to say that it’s good. That’s what I wanted to show, this life of a work of art. And this work of art, what is it? I’d have to approach it, but that’s impossible. And then all that we find there, all that we look for in a book, and which has nothing to do with its literary value.

There is often a multitude of voices in that book.

It’s like that in most of my books that come later. There are all these voices, without our needing to take an interest in the characters that speak them. It doesn’t much matter.

Have there been processes that repeat themselves, either in the conception or in the elaboration of the novels?

Each time it didn’t interest me to continue doing the same thing. So, I would try to extend my domain to areas that were always at the same level of these interior movements, to go into regions where I hadn’t yet gone.

Have you ever been surprised by the fate of one of your books?

No. I was more pessimistic at the start. I really thought that it would not be at all understood.

You’ve said that the nouveau roman movement helped you as a means to get read. But did the idea of belonging to a movement, so-called, constrain you as well?

No. And none of those who belonged, who were classed in this movement, have written things that resemble each other, whatever it may be. They’ve remained completely different from each other, and have continued each one in his own path.

Your essays were among the first to speak of concerns common to the group. Have you ever felt any sort of responsibility to this movement?

Not at all. I had reflected upon these questions about the novel before the others, because the others were twenty years younger than me. I haven’t changed my way of thinking since my first books, I haven’t budged. I could repeat exactly the same things I said when I wrote The Age of Suspicion. It is a deep conviction that the forms of the novel must change, that it’s necessary there be a continual transformation of the forms, in all the arts—in painting, in music, in poetry, and in the novel. That we cannot return to the forms of the nineteenth century and set another society in them, it doesn’t matter which. So, that interested Alain Robbe-Grillet; he’s the one who did a lot to launch the nouveau roman. He was working at Les Editions de Minuit, he wanted to republish Tropisms, which had been out of print. It came out at the same time as Jealousy, and at that moment in Le Monde a critic had written, “That is what we can call the nouveau roman,” though he detested it. It was a name that suited Robbe-Grillet quite well. He said, “That’s magnificent, it’s what we needed.” He wanted to launch a movement. Me, I’m incapable of launching a movement; I’ve always been very solitary.

Were there ever any meetings of the group?

Never. Nor discussions. It had nothing in common with the surrealists, where there was a group, a leader, André Breton, nothing of the kind. We never saw each other.

How did he find all the writers to bring them together as a movement?

It was Les Editions de Minuit. Robbe-Grillet found Michel Butor, who had written Passage de Milan, which they published. He found Claude Simon. Robert Pinget as well. Robbe-Grillet and Jérôme Lindon, who is the director of Les Editions de Minuit, they worked together. Like that they formed a sort of group.

Have there been other experimental literary movements that have interested you?

No, I passed them by entirely. The surrealist movement, for example, that might have interested me, but it didn’t at all.

What about the Oulipo movement in the 1960s, which included Georges Perec, Raymond Queneau, Italo Calvino?

I liked what Queneau was doing a lot. My first book, Tropisms, appeared in the same collection as his book, The Bark Tree, with the publisher Robert Denoël. I quite liked The Bark Tree.

In Between Life and Death (1968), your novel on literary creation, you say that no work is useless, that sooner or later it must give fruit, that it suffices to pick it up again later at the right moment. Have you had that experience, of reworking a text you’d written?

No. I meant that every effort we make always serves for something, all the same. There are certain texts that were projected for Tropisms that I brought out later in Portrait of a Man Unknown.

Which of your books do you prefer?

That’s very difficult to say. I don’t reread them. And sometimes I tell myself, “But it seems to me I’ve already done something like that,” and I can’t recall where.

Has one of the books satisfied you more than the others?

It’s all very difficult. There are always doubts, in regard to what I wanted to do.

Even the doubts, have they played a constructive role sometimes?

I don’t know. I think it’s very painful, and that it’s better not to have any. I envy those who don’t have any, I envy them a lot. They are happy people.

In Do You Hear Them? (1972), it seems that every movement starts from a central balance: on one side, the two friends and their pre-Colombian stone that they’re admiring; on the other side, the children upstairs and their laughter. What impelled you to explore this dynamism?

I’ve always been interested by the relation between a work of art, the desire to communicate, and what the work of art brings you. Also, the relation between people who love each other a great deal. I thought it was an amusing construction, I don’t know. Each time there is a point of departure, but you know it’s hardly conscious. It comes and one doesn’t know how, nor why.

We are far from autobiography in your work, so readers and critics end up by being curious about your life. You give little importance to all that. Why, do you think, do so many serious writers insist on not writing autobiography in their books?

I think that in every book we put a lot of experience that we have ourselves lived more or less, or imagined ourselves. There is not a single book that doesn’t contain such experience. Even with Kafka, he didn’t live The Trial, but there is a whole universe in which he lived, which was close to him and which he translated by The Trial, or The Castle. It’s a transposition, it’s a metaphor for something that he felt very strongly. And that we all feel as well.

But it seems sometimes there is a sort of mistrust of autobiography.

When it’s a real autobiography. That is, one wants to display everything one has felt, how one has been. There is always a mise en scène, a desire to show oneself in a certain light. We are so complex and we have so many facets, that what interests me in an autobiography is what the author wants me to see. He wants me to see him like that. That’s what amuses me. And it’s always false. I don’t at all like Freud and I detest psychoanalysis, but one of Freud’s statements I have always found very interesting, and true, when he said that all autobiographies are false. Obviously, because I can do an autobiography that will show a saint, a being who is absolutely idyllic, and I could do another that will be a demon, and it will all be true. Because it’s all mixed together. And in addition, one can’t even attain all that. When I wrote Childhood, I stopped at the age of twelve, precisely because it’s still an innocent period in which things are not clear and in which I tried to recover certain moments, certain impressions and sensations.

Fools Say (1976) was the last novel you wrote. It seems the most abstract of your books.

It’s more difficult, the construction is difficult. It works on two planes: there is on the one hand the character, he who acts like a character, and then the idea which is attributed to an “intelligent” character or to a fool. And this idea only has value by the fact that it is attributed to someone of repute. It can be stupid but we can’t say so, because it was that person who thought that. On the contrary, the one who has been defined as a fool, whatever he may say, he might be very intelligent sometimes, we say that it’s stupid. The idea has no freedom, it’s not taken on its own, because it is always attributed to someone. Later, when I had written my book, someone wrote me that Lenin had said, “We must destroy the fools.” Who were the fools? Those who didn’t think like him. That’s what I wanted to show in my book. So, for that I had to create characters. The character of the genius, the character of the fool. But what is a fool? He may be a fool when it’s a question of mathematics or political science, and he might be remarkably intelligent when it’s a question of something else. Each one of us is at the same time very intelligent and a fool. It depends what is asked of him. It’s a lack of freedom to declare, “That’s what fools say.” To class people as fools is already a fascist attitude. It’s entirely totalitarian, entirely arbitrary, and absolutely unspeakable. One should say, “That idea there is a stupid idea.” But we cannot say of someone, “He’s a fool.” Because that fool may be much more intelligent than Einstein or whomever on another matter.

Did you decide to not write any more novels after that?

No, I never made any decisions. And then, I’ve never considered them as real novels in the traditional sense.

What are you working on now?

Now too it’s something in a form that I’ve never used, and I don’t know what it will be. I’ve got about two-thirds of the book now, but I’m not in so much of a hurry to finish it. I don’t know what I’ll do after.

Your book The Use of Speech (1980) recalls your first book, Tropisms. Again there are brief texts completely separate from each other, though here you look at certain things around a specific word, how it works.

As it’s called The Use of Speech, it always starts off from the spoken word. The word falls there like a stone and makes eddies.

Was it conceived as a book from the start?

It was conceived in advance that each of its texts was around a word, whereas Tropisms was not conceived in advance. There I’d written the texts one after the other, without really knowing what I was in the process of doing.

Your most recent book, Childhood, is altogether different once again. Why did you use the form of dialogue to recall these memories?

That came about naturally, because I told myself, “It’s not possible for you to write that.” Until that point, I had always written fiction. I had a great freedom, I invented situations in which I placed, under a certain light, things that interested me. And in Childhood I would be bound to something that was fixed, that was already past. It was the contrary of everything I’d done. So I told myself, “You cannot do that.” I noted down this dialogue, and it served me for the start of my book. After that, all through the book I had this second conscience, which was a double of myself, and which controls what I’m doing, which helps me advance.

The memories in the book often work like tropisms.

I chose memories where there were tropisms, as much as possible, that’s what interested me. It gives movement to the form.

Portions of this interview were first published in Exquisite Corpse (Baton Rouge) 6:10-12 (Oct.-Dec. 1988); the entire text appeared in The Paris Review (New York) 114 (Spring 1990), and later in Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (Iowa, 1991), now out of print.

Nathalie Sarraute (1900-1999) was eighty-three when she first published a bestseller, Childhood (1983). Unlike her previous books, it treated autobiographical events. In the book, memories from her Russian and French childhood emerge from a word or a gesture recalled, burn brightly for a moment, and fade. Quietly the mosaic takes shape in her compassionate regard for the parents whose early divorce divided her love.

Born in Ivanovo, near Moscow, Sarraute made a lifetime of seeing inside being human. Her first book, Tropisms (1939), a collection of brief texts, marked a fresh direction in French literature and established her as the first of what came to be known as the nouveau roman group of writers. She described tropisms as the “interior movements that precede and prepare our words and actions, at the limits of our consciousness.” They happen in an instant, and apprehending them in the rush of human interactions demands painstaking attention. Tropisms became the key to all her subsequent work.

Highly respected in France, Sarraute has been translated into twenty-four languages; her eight novels and other books are all available in English. Since the 1960s she traveled often, invited to universities around the world. Her husband, whom she met in law school, always accompanied her. She visited the United States every few years, and was last in New York in September 1986, for the American premiere of her play Over Nothing at All. In the fall of 1990 she was invited to visit the house where she was born in Ivanovo.

For decades, Sarraute went every morning to write at the same neighborhood cafe in Paris. The following interview took place on two cold January afternoons in 1987, at her home in the sixteenth arrondissement near the Musée d’Art Moderne.

In your books you have a very fine ear, for the interior voices as well as for the development of the text. Another domain of listening, of course, is music. Do you listen much to music?

I like music a lot, almost too much. Sometimes so much even that it gives me a sort of feeling of anguish. But I haven’t listened a lot, partly because of that. It’s quite curious, the effect it has on me. And precisely in the works I prefer, it’s a sort of anguish that I never have from painting, which always gives me a feeling of eternity, security, peace. Of immobility. I love painting a great deal. Music at times reaches something that is almost superhuman, divine. One listens to Mozart and says, It’s not possible that a human being did that.

Were you ever tempted to write another sort of literature, such as the fantastic?

Not at all. Because each instant of the real world is so fantastic in itself, with all that’s happening inside it, that it’s all I want.

At the time of your first book, Tropisms, what was your rapport with the literary world?

I didn’t know anyone, not a single writer. I didn’t meet Sartre until the war. After the Liberation, he wrote the preface for my first novel, Portrait of a Man Unknown (1947).

How did you arrive at the form of those first short texts?

The first one came out just as it is in the book. I felt it like that. Some of the others I worked on a lot.

And why did you choose the name Tropisms?

It was a term that was in the air, it came from the sciences, from biology, botany. I thought it fit the interior movement that I wanted to show. So when I had to come up with a title in order to show it to publishers, I took that.

How did you know what they were at the time, these tropisms? How did you know when you’d found one?

I didn’t always know, I might discover it in the writing. I didn’t try to define them, they just came out like that.

The tropisms often seem to work through a poetic sensibility.

I’ve always thought that there is no border, no separation, between poetry and prose. Michaux, is he prose or poetry? Or Francis Ponge? It’s written in prose, and yet it’s poetry, because it’s the sensation that is carried across by way of the language.

With the tropisms, did you feel that it was fiction? Did you wonder what to call it?

I didn’t ask myself such questions, really. I knew it seemed impossible to me to write in the traditional forms. They seemed to have no access to what we experienced. If we enclosed that in characters, personalities, a plot, we were overlooking everything that our senses were perceiving, which is what interested me. One had to take hold of the instant, by enlarging it, developing it. That’s what I tried to do in Tropisms.

Did you sense at the time that was the direction your work would go?

I felt that a path was opening before me, and which excited me. As if I’d found my own terrain, upon which I could move forward, where no one had gone prior to me. Where I was in charge.

Were you already wondering how to use that in other contexts such as a novel?

Not at all. I thought only of writing short texts like that. I couldn’t imagine it possible to write a long novel. And after, it was so difficult finding these texts, each time it was like starting a new book all over again, that I told myself perhaps it would be interesting to take two semblances of characters who were entirely commonplace as in Balzac, a miser and his daughter, and to show all these tropisms that develop inside of them. That’s how I wrote Portrait of a Man Unknown.

In effect, one could say that all or most tropisms we might find in people could also be found in a single person.

Absolutely. I’m convinced that everyone has it all in himself, at that level. On the exterior level of action, I don’t for a minute think that Hitler is like Joan of Arc. But I think that at that deep level of tropisms, Hitler or Stalin must have experienced the same tropisms as anyone else.

The tropisms would seem to enter the domain of the social sciences as well.

Yes. I’ve become more accessible, besides. It used to be entirely closed to people. For a long time people didn’t get inside there, they couldn’t manage to really penetrate these books.

Why do you think that is?

Because it’s difficult. Because I plunge in directly, without giving any reference points. One doesn’t know where one is, nor who is who. I speak right away of the essential things, and that’s very difficult. In addition, people have the habit of looking for the framework of the traditional novel—characters, plots—and they don’t find any, they’re lost.

That brings up the question of how to read these books. You do without plot, for example.

There is a plot, if you like, but it’s not the usual plot. It is the plot made up of these movements between human beings. If one takes an interest in what I do, one follows a sort of movement of dramatic actions which takes place at the level of the tropisms and of the dialogue. It’s a different dramatic action than that of the traditional novel.

You’ve said that you prefer a relatively continuous reading of your books. But all reading is a somewhat fragmentary experience. With a traditional novel, when one picks it up again to continue reading, there are the characters and the plot to situate oneself, where one left off. In your books, do you see other ways of keeping track of where one was?

I don’t know. I don’t know how one reads it. I can’t put myself in the reader’s place, to know what he’s looking for, what he sees. I have no idea. I never think of him when I’m writing. Otherwise, I’d be writing things that suit him and please him. And for years he didn’t like it, he wasn’t interested.

Even after several books you weren’t discouraged?

No, not at all. I was always supported, all the same, from the start. With Portrait of a Man Unknown, I was supported by Sartre. At the time, Sartre was the only person who was doing something about literature, he had a review. My husband as well was tremendously supportive, from the very start. He was a marvelous reader for me, he always encouraged me a great deal. That was a lot. It suffices to have one reader, who realizes what you want to do. So, it was a great solitude, if you like, but deep down inside it wasn’t solitude. Sartre was impassioned by Portrait of a Man Unknown. So, that was very encouraging. Then when Martereau (1953) was done, Marcel Arland was very excited and had it published with Gallimard. He was editing the Nouvelle Revue Française at the time. I always had a few enthusiastic readers. When Tropisms came out, I received an enthusiastic letter from Max Jacob, who at the time was very admired as a poet. I can’t say it was a total solitude.

Did Sartre or others try to claim you as an existentialist?

No, not at all. He had published the beginning of Portrait of a Man Unknown in his review, Les Temps Modernes, and then he wrote the preface because he wanted to. And he told me, “Above all, they shouldn’t think it’s a novel that was influenced by existentialism.” Which couldn’t be the case, because Tropisms came out almost the same time as Nausea.

It was rather another existentialism.

He was entirely conscious of that. And very honestly he said, “It is existence itself.”

You’ve said that it was during your law studies that you became attracted to the spoken language, which became your written language in effect. How did that opening come about?

When I was working in law I didn’t practice much, but I prepared probate conferences, which were literary; one said them, it’s a spoken style. I’d worked those conferences a lot, they went well. And so, I think that tore me away from the written language, which I’d always been subjected to since childhood by the very strict French homework. It gave me a kind of impetus toward the freer language, which is spoken French. It did play some role.

The language seems lighter, there’s a greater facility in the flow of the writing.

That facility demands an enormous amount of work. What a job!

Did you look for models elsewhere?

No, I never thought of comparisons. They were things that I felt spontaneously, really. It wasn’t taken from literature but from life rather.

Do you imagine other ways of writing about the tropisms?

No, because for me form and content are inseparable. So, that would be something else. If the form is different, it will be another sensation. And for this genre of sensation, it’s the only form.

Do you feel there are other writers who have found certain lessons in the domain of tropisms?

I don’t feel I have any imitators. I think it’s a domain that is too much my own.

Would it be possible to use the tropisms in a more traditional novel?

I don’t see how. What interest would there be? Because in a more traditional novel, one shows characters, with personality traits, while the tropisms are entirely minute things that take place in a few instants inside of anybody at all. What could that bring to the description of a character? On the contrary.

As if at the moment of the tropisms, the character vanishes.

He disintegrates, before the extraordinary complexity of the tropisms inside of him.

Which is what happens in Martereau.

Martereau disintegrates. And in Portrait of a Man Unknown, the old man, the father, becomes so complex that the one who’s looking to see inside of him abandons his quest, and at that moment we end up with a character out of the traditional novel, who ruins everything. In Martereau, it’s the character out of the traditional novel who disintegrates at the end.

Yet in The Planetarium (1959), it seems that more than ever you’re using traditional characters.

On purpose. Since they are semblances, it’s called The Planetarium, and is made up of false stars, in imitation of the real sky. We are always for each other a star, like those we see in a planetarium, diminished, reduced. So, they see each other as characters, but behind these characters that they see, that they name, there is the whole infinite world of the tropisms, which I tried to show in there.

Considering the interior nature of your writing, has it sometimes been difficult to remain at such depths?

No, what is difficult is being on the surface. One gets bored there. There are a lot of great and admirable models who block your way. And once I rise to the surface, to do something on the surface, it’s easy, but it’s very tedious and disappointing.

In Portrait of a Man Unknown the specialist consulted by the narrator tells him: “Beware of this taste for introversion, for daydreaming in the void, which is nothing but an escape before the effort.”

Yes, because he feels that he is marginal, he feels that he’s not normal. It’s entirely ironic. He goes to see a psychiatrist who tries to put him on the right path. In my books there are always these normal people who don’t understand these tropisms, who don’t feel them.

With Portrait of a Man Unknown, had you decided to avoid using characters?

No, on the contrary, I wanted to take semblances of characters, types, the miser for example, like Père Grandet, and then to try to see what really happens in him, which is of an enormous complexity. It is so complex that the character who is searching him out abandons the search, he can’t go on anymore. And at that moment the character from the traditional novel is introduced, who has a name, a profession, who marries the daughter, etcetera. We fall back into the traditional novel and dialogue.

While you were writing this book, did you know how it was going to end?

No, I found the ending when I got to the end. Usually, it develops like that, like an organism that develops. Often I don’t see the ending at all, it comes out of the book on its own.

You’ve said that with the novels you wrote the first draft directly from beginning to end.

At first. I always have to make a beginning that’s entirely finished, the first few pages must be fixed in place. Like a spring-board, that I take off from, I don’t rework it any further. I work on it a lot, and then it’s finished. But after that, I wrote from one end to the other. I used to work like that, not now. I wrote from one end to the other, in a form that was sometimes a bit rough, I found the general movements, and then I rewrote the whole thing. For a while now, though, I’m afraid of waiting two or three years like that before starting over. So, I write gradually, I finish each passage as I go along. I changed my system about six years ago, since The Use of Speech and Childhood.

In Martereau the narrator speaks of the importance of words, of what they hide. For Martereau, who is rather a traditional novelistic character, words are “hard and solid objects, of a single flow.” One would say that in your books you feel a certain seduction of words.

Yes, it’s words that interest me. Inevitably. It’s the very substance of my work. As a painter is interested in color and form.

Some say the most important problem in the novel is time. In your book of essays, The Age of Suspicion (1956), you said that “the time of the tropisms was no longer that of real life but of an immeasurably expanded present.” In the novels time is surely complicated then.

There are always instants. It takes place in the present finally. I’m concerned with these interior movements, I’m not concerned with time.

Is that because you often do without plot?

Completely. It has to do with a dramatic development of these interior movements, that’s the time. There is no exterior reference.

So then it’s a sort of freedom from time.

Time is absent, if you like.

How was it you realized you could do without plot in the first place?

The question never posed itself for me. Given what I was interested in, plot didn’t enter into it. I was involved as with a poem, one writes a poem and isn’t concerned with such matters as plot. It was a free territory, there were no pre-established categories that I was obliged to enter into.

In effect there are quite a few correspondences with poetry in your work.

I hope so. There was a book by an Australian, on my novel Between Life and Death, who called it a “poetry of discourse.” He called it a novelistic poetry. Not a poetic novel, because that’s been done.

Have you read a lot of poetry?

Not especially. I’ve read some. You know, outside reading has not played a big role in my work.

Well, what sort of reading was important for you?

What really turned me around was reading Proust, it was a revelation of a whole world, and reading Joyce too. The interior monologue of Joyce. They’re things without which I wouldn’t have written as I do. We always start from our predecessors. If I’d written in the eighteenth century, I wouldn’t have written like that. There had to be writers like that before me, who opened up such realms.

Were you fairly young when you read them?

Yes. I read Proust when I was twenty-four, and Joyce at twenty-six.

In your essay, “From Dostoyevsky to Kafka,” you say that Kafka “traced a long straight path, a single direction and he went all the way.” Don’t you think there is any continuation beyond him?

I don’t think so. They’ve sought to imitate him a lot, at a certain moment it was fashionable to write like Kafka, but in my opinion that didn’t lead anywhere.

It seems, however, that there is more than a single direction in Kafka. There are various levels, that of the story, of the way he tells it, but there is also the poetic dimension, the parables.

I wasn’t concerned with all that. It was a period when there was a hate, a mistrust, of “psychology.” People were divided between those who were for Dostoyevsky, and those for Kafka, that is against psychology. At the time, I didn’t know Kafka’s work at all. I read Kafka very late, after the Liberation. I didn’t like “The Metamorphosis,” I only liked The Trial and The Castle. So, they were opposing Kafka with Dostoyevsky; in Kafka they said there was emptiness, no psychology. I wanted to show that even in Kafka there was psychology, we can’t do without it. It was a psychology pushed to the ultimate despair, the total absence of human contact. I was never concerned with a full analysis of Kafka, I’m not a critic. And then Kafka is not an author who influenced me. I must have been about forty-five by the time I read him.

The central concern of the essay was with the psychological.

That’s right. I wanted to defend this conscience that was so despised, which Kafka supposedly didn’t have. I found that he had a lot of it, and that every writer worthy of that name cannot do without the internal life.

Elsewhere in that essay you made a distinction between the characters in the work of those two writers, saying that “while the quest of Dostoyevsky’s characters leads them to seek a sort of interpenetration, a total and always possible fusion of souls, with Kafka’s heroes it has to do with simply becoming, ‘in the eyes of those people who regard them with such scorn,’ not perhaps their friend but finally their co-citizen.” Isn’t this distinction a condition of the Christian and Jewish contexts of the two writers?

I never got involved with that question, because I think that what’s interesting there is to step outside of those contexts and to see the human being in depth. Kafka’s universe has become a part of our own universe, and the Jewish question doesn’t intervene at all. Moreover, neither in The Castle nor in The Trial does he speak of it. We have the right to deal with that if the author himself puts it in his work. But if it remains outside, I don’t see why a Christian couldn’t read Kafka’s The Trial or The Castle in the same way as a Jew. It addresses itself to everyone, that’s why it’s a great work.

I was thinking more of their cultural formations.

I’m not concerned with that. I’m not a critic. I’m concerned with what touches me directly as a writer.

In one of the essays you also quote Katherine Mansfield’s phrase, “this terrible desire to establish contact.” But once a person takes off on a more experimental path, like yours for example, what becomes of that need? Were you yourself thinking along such lines?

No, when I work I never ever define from the outside, I don’t qualify what I’m doing. I’m looking to see what is felt, what do we feel. I don’t know what it is, and that’s why it interests me, precisely because I don’t know exactly what it is. Those were theoretical essays, they have nothing to do with my work when I write. I don’t put myself at that distance, I’m entirely inside.

In the essay “The Age of Suspicion,” you said that the novel “has become the place of the reciprocal mistrust” of the reader and the writer. Do you think that with the contemporary novel that mistrust has gotten deeper, more serious?

That’s an entirely personal question. I’m not terribly interested, except when I’m reading Agatha Christie or novels that carry me away, in the personalities of the characters nor in the plot. When I see a novel written in that form, it might amuse me, it can be slices of life or descriptions of manners, but I can’t say that it interests me as a writer. There are those who like that, obviously, people do continue to write in that way.

Do you feel, for example, that the contemporary novel has become more conservative?

There was a period when we fell back joyfully into the tradition. There was a strong academic tendency, in the theater as well, everywhere. And I think all the same we’re getting out of that once again. The admiration for academicism is declining.

If there is such a thing as an evolution of the novel, do you see it as a one-way street?

I’m not a critic, you know. I only read what interests me, what passes my way. I don’t have any opinion on the current evolution of literature. I think that the writers who were grouped under the term nouveau roman have all continued to write each in his way, works which have remained alive for the most part.

On various occasions, especially in your essay on Flaubert, you’ve spoken about dispensing with the old accessories such as plot and characters. But are those old accessories so useless as that, are there no truths to be reached with them?

One reaches certain truths, but truths that are already known. At a level that’s already known. One can describe the Soviet reality in Tolstoy’s manner, but one will never manage to penetrate it further than Tolstoy did with the aristocratic society that he described. It will remain at the same level of the psyche as Anna Karenina or Prince Bolkonsky. If you use the form that Tolstoy used. If you employ the form of Dostoyevsky, you will arrive at another level, which will always be Dostoyevsky’s level, whatever the society you describe. That’s my idea. If you want to penetrate further, you must abandon both of them and go look for something else. Form and content are the same thing. If you take a certain form, you attain a certain content with that form, not any other.

But even so, the form is something you’ve discovered each time.

Each time it has to find its form. It’s the sensation that impels the form.

In your essay “Conversation and Sub-conversation” you speak of certain ideas that Virginia Woolf and others had about the psychological novel, saying that perhaps it hasn’t yielded as much as they had hoped at the time.

That was meant ironically. I agreed with her. I don’t really like the word “psychological,” which has been used a lot, because that makes one think of traditional psychology, the analysis of feelings. But I would say that the universe of the psyche is limitless, it’s infinite. So, each writer can find there what he would like. It’s a universe as immense as we all are, and there are writers yet who are going to discover huge areas of the life of the psyche, that exist but which we haven’t brought to light.

In the same essay you also speak of the American example, as a reason to look beyond the psychological. Who were you thinking of, besides Faulkner?

The behaviorists, they were completely against that. Steinbeck, Caldwell, that wasn’t psychological at all. It was because of them that psychology was despised. It had a big influence, besides, on people like Camus, with The Stranger. It was fashionable at the time to say that there was no conscience, that it held no interest.

In “Conversation and Sub-conversation,” you particularly discuss the problem of how to write dialogues now, so that the sub-conversation may be heard. How did you arrive at your manner of reaching all those levels at once, in the way you write dialogue? Was it by a lot of experimenting?

No. That comes uniquely from intuition, it represents a big job of searching, in order to reconstitute all these interior movements. To relive it. To expand it, to show it in slow motion. Because it is very fleeting. It gets erased very quickly. And it’s very difficult to get ahold of.

You’ve written that the traditional methods of writing dialogue couldn’t work anymore.

Not for me. Because I would have to put myself at too much of a distance from the consciousness in which I dwell. I’m immersed right inside, and I try to execute the interior movements that are produced in that consciousness. And if I say, “said Henri” or “responded Jean,” I become someone who is showing the character from outside.

One of the things that marks your writing is the punctuation, which you work very carefully.

In the last few books there are a lot of ellipses; there were less of them before. Because I find that it prevents one from reading these movements, which are very quick and suspended, without breathing. There is need for a certain breathing when one reads it, and the ellipses create this breathing. They help in the rhythm of the sentence. It gives the sentence more flexibility.

Let’s talk about your theater work. Why did you start writing plays?

It was simply a request by the radio in Stuttgart. A young German, Werner Spiess, came to see me for the radio in Stuttgart, he asked me to write a radio play. That was in ‘64. He wanted something new, in a style that wouldn’t be like the usual style; it didn’t matter if it were difficult even. I started by refusing. He returned a second time, and I refused again. And then I thought about it one day. I told myself that perhaps all the same I could write a radio play, that it would be entirely a matter of the dialogue. I hadn’t thought I would be able to do it because for me the dialogues are prepared by the sub-conversation, the pre-dialogue. The dialogue only skims the surface of the sub-conversation. So, I decided everything will be in the dialogue, what is in the pre-dialogue will be in the dialogue. They later said my plays, in relation to my novels, were like a glove turned inside out. Everything that is inside, is now on the outside.

Which play was that?

First it was Silence, then The Lie, then the four other plays. They were always performed first for foreign radio.

That’s why you put hardly any directions in the text, because they were written for the radio.

That’s right, because they’re not written for the stage. There’s only one where I was thinking of the stage, that was It Is There. And still, not a lot. Above all, I hear the conversations and the voices, and I don’t see at all the theatrical space, the actors. All that is the job of the director. Which is a very interesting job, because everything remains to be done.

Have you attended rehearsals much?

Yes, I’ve attended rehearsals. First, with Jean-Louis Barrault, then with Claude Régy, then with Simone Benmussa. I don’t have a lot to say, except for the intonations, but not for the actors’ movements. That’s the director’s job.

Were all the plays requests like the first one?

It was always for the radio, always the same person who asked me. Then, after the radio in Stuttgart didn’t do difficult plays anymore, it was the radio in Cologne. And French radio too. Each time after having finished a novel, I rather liked writing a radio play. It distracted me, it gave me a bit of a change.

Did you have much experience of the theater apart from your plays?

I liked going to the theater, of course. I was quite impressed by Six Characters in Search of an Author by Pirandello, and The Dance of Death by Strindberg. Those two plays deeply impressed me.

You’ve said that your plays are like a continuation of your novels. What has the theater brought you for the writing of your novels?

Absolutely nothing. It has no relation whatsoever.

Are there voices in the modern theater that have particularly interested you?

No, not so much. Some of Pinter’s plays I’ve quite liked. Where he touches on things that interest me.

Has the experience of writing changed much for you since you were young? Do you have different habits?

I don’t feel that it’s changed. I think we always have the same difficulties with each new book; there is no acquiring of experience. Each new book is entirely another realm, in which one must try to find its form and its sensations, and the difficulties are the same as at the start. I see no progression. There is no technical experience gathered for me.

Was writing much different for you when your children were young?

No. I started to write when the third daughter wasn’t yet born, the two others were little; that played no role. I always had enough time for myself. You know, I don’t believe that women of the bourgeoisie can pretend they can’t write because they have children. That’s absurd. Claudel was the French ambassador in Washington and wrote an immense body of work; he never ceased to be ambassador and all that that represents. So, when you’ve got someone to take care of the children, and after when they go to school, it’s impossible not to find two or three hours in the day to work. It’s very different for a working-class woman, or for a working-class man, it’s the same problem. Not entirely the same, because the woman has still more work to do than the man. But there I understand completely that it’s impossible. One can’t speak like that of women from the intellectual milieu, which is always a bourgeois milieu. Especially before, since now it’s become more difficult, but before one found whatever one wanted for taking care of the children. There was no problem as far as that was concerned.

Considering the interior quality of your writing, do you see the fact of being a woman as giving you any special access to such a state? As if that predisposed you toward the interior rather than out toward action in the world.

No, I don’t think so at all. I don’t think that Proust or Henry James or even Joyce were turned elsewhere than toward the inside. It’s a question of the writer’s temperament.

Do you see any sort of difference between women’s writing and that of men?

No, I don’t see any. I don’t feel that Emily Brontë is a woman’s writing, among women who truly wrote well. I don’t see the difference. One says first of all, “That’s what it is to be a woman,” and then after one decides that is feminine. Henry James was always working in the minute details, in his lacework; or Proust, much more still than most women. I think that if women like Emily Brontë wanted to keep a pseudonym, they were entirely right. One cannot find a manner of writing upon which it would be possible to stick the label of feminine or masculine; it’s writing pure and simple, an admirable writing, that’s all. There are subjects in writing that are very feminine, which are lived, the women who write on feminine subjects like maternity, that’s completely different.

Let’s talk about cigarettes. Have you always been a smoker?

Alas! I shouldn’t smoke, but I don’t smoke a lot. Six or seven cigarettes a day. That’s still too much. I have a very bad habit. So, in order not to smoke, I’ve taken to holding the cigarette in my mouth while I work. I don’t light it. That gives me the same effect. Because I forget. I feel something and I forget if it’s lit. Since I smoke very weak cigarettes, and I don’t swallow the smoke, I have just as much the impression of smoking even if it’s not for real.

As if it enters into the game, in effect.

That’s right. It’s a gesture, something one feels.

Could we speak about the conception of some of your books? The Golden Fruits (1963), for example, did that come out of an experience with the literary world?

Not at all. I take no part in the literary world, I’ve never gone to the literary cocktail parties. It has to do with an inner experience. It has to do with a kind of terrorism around a work of art that is lauded to the skies and which we cannot approach. Where there is a sort of curtain of stipulated opinions that separates you from that work. Either we adore it or else we detest it, it’s impossible to approach it; above all in the Parisian milieu, even without going to the cocktail parties, even in the press, there reigns a kind of terrorism of general adulation, and you don’t have the right to approach it and have a contrary opinion. And then it falls; at that moment you no longer have the right to say that it’s good. That’s what I wanted to show, this life of a work of art. And this work of art, what is it? I’d have to approach it, but that’s impossible. And then all that we find there, all that we look for in a book, and which has nothing to do with its literary value.

There is often a multitude of voices in that book.

It’s like that in most of my books that come later. There are all these voices, without our needing to take an interest in the characters that speak them. It doesn’t much matter.

Have there been processes that repeat themselves, either in the conception or in the elaboration of the novels?

Each time it didn’t interest me to continue doing the same thing. So, I would try to extend my domain to areas that were always at the same level of these interior movements, to go into regions where I hadn’t yet gone.

Have you ever been surprised by the fate of one of your books?