_Music Documentaries

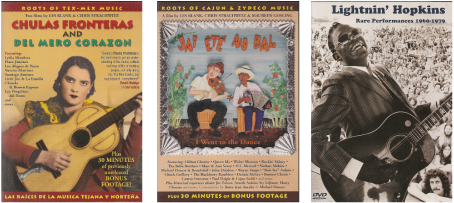

Les Blank & Chris Strachwitz, Chulas Fronteras and Del Mero Corazón (Brazos)

Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz & Maureen Gosling, J’ai Été au Bal (Brazos)

Lightnin’ Hopkins, Rare Performances 1960-1979 (Vestapol/Rounder)

Ramble to Cashel: Celtic Fingerstyle Guitar (Vestapol/Rounder)

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 4 (Fall 2003)

I never caught Chulas Fronteras (1977) when it first came out, but I heard the records and knew it was a landmark documentary on Tex-Mex border music. So, when I watched its new release on DVD, I wondered would the years be kind. Sure I could smell the meat sizzling on the grill (forget doctor’s orders), but most pungent was the testimony into the realities of these lives—musicians (Lydia Mendoza, Flaco Jiménez), local record producers, farmworkers. I was glad to be spared the dust and the heat, yet even at this distance the daily cause and effect that gives rise to the music, with its history of migrations, felt immediate. Ethnographic filmmaker Les Blank has been justly praised for the vibrancy of his work, and together with Arhoolie Records founder Chris Strachwitz who initiated the project, they managed to see through to the heart of the songs.

A decade later, they teamed up again on J’ai Été au Bal, about the Cajun and Zydeco music of southern Louisiana. We may well be moved to ask: Why does the liveliest music so often derive from the poorest people in the sweatiest places? Because they have nothing else? Again, the life, the lore, the laughter, as conveyed in the film, bring us kitchen-table close to a distinct American culture. Without that kind of feeling for the people, hearing a few records of this music (the Balfa Brothers, Queen Ida, Clifton Chenier) just isn’t the same. With fiddler Michael Doucet and guitarist/accordionist Marc Savoy as our guides, the film traces the intertwined development of the two styles, both born from the merging of French and African-American traditions. Due no doubt to a comparable mix of origins and social conditions, Cajun and Zydeco most resemble the exuberant forró music, also accordion-driven, of the Brazilian northeast. There is always a party in that bayou music, and this film has a way of calling us to the party.

Concert films, by contrast, fall curiously flat much of the time. Projecting the illusion of a three-dimensional experience, in a nearly empty room, doesn’t take the place of being there. But since that is often not possible, we must settle for the document. The advantage posed by the collection Lightnin’ Hopkins, Rare Performances 1960-1979 is that we gain a different kind of depth, viewing him over time, in a variety of settings. Thus we may appreciate Hopkins’s irreducible qualities as a musician, his essential poetry and grace. First seen playing on the street and in a Houston bar, not long after his rediscovery, he seems already a master of timing and lyric economy. Later, he performs for folklorists in Seattle, then in a PBS studio concert, and finally on the show “Austin City Limits” where he has gone electric, enjoying his wah-wah pedal. He remains poised throughout, on slow burn but with a smile, always making those blues runs look so easy on his guitar.

Vestapol’s numerous anthology DVDs are likewise drawn from many sources, but Ramble to Cashel presents seven Celtic fingerstyle guitarists each in the same cold studio conditions. This may be just as well, for one of Vestapol’s aims is pedagogical; the footage here grants little distraction, so we may concentrate on watching formidable technique while listening to the prettiest tunes. Indeed, these musicians—Martin Simpson, Pierre Bensusan, Duck Baker, among them—mostly hunch over their instrument, often with eyes closed, like dervishes lost to a flame of their own making. Watching the finely worked-out fingerings, and the intricate embellishments to these traditional pieces, we get a sense of how very much work was involved to produce each little gem.

* * *

Les Blank & Chris Strachwitz, Chulas Fronteras and Del Mero Corazón (Brazos)

Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz & Maureen Gosling, J’ai Été au Bal (Brazos)

Lightnin’ Hopkins, Rare Performances 1960-1979 (Vestapol/Rounder)

Ramble to Cashel: Celtic Fingerstyle Guitar (Vestapol/Rounder)

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 4 (Fall 2003)

I never caught Chulas Fronteras (1977) when it first came out, but I heard the records and knew it was a landmark documentary on Tex-Mex border music. So, when I watched its new release on DVD, I wondered would the years be kind. Sure I could smell the meat sizzling on the grill (forget doctor’s orders), but most pungent was the testimony into the realities of these lives—musicians (Lydia Mendoza, Flaco Jiménez), local record producers, farmworkers. I was glad to be spared the dust and the heat, yet even at this distance the daily cause and effect that gives rise to the music, with its history of migrations, felt immediate. Ethnographic filmmaker Les Blank has been justly praised for the vibrancy of his work, and together with Arhoolie Records founder Chris Strachwitz who initiated the project, they managed to see through to the heart of the songs.

A decade later, they teamed up again on J’ai Été au Bal, about the Cajun and Zydeco music of southern Louisiana. We may well be moved to ask: Why does the liveliest music so often derive from the poorest people in the sweatiest places? Because they have nothing else? Again, the life, the lore, the laughter, as conveyed in the film, bring us kitchen-table close to a distinct American culture. Without that kind of feeling for the people, hearing a few records of this music (the Balfa Brothers, Queen Ida, Clifton Chenier) just isn’t the same. With fiddler Michael Doucet and guitarist/accordionist Marc Savoy as our guides, the film traces the intertwined development of the two styles, both born from the merging of French and African-American traditions. Due no doubt to a comparable mix of origins and social conditions, Cajun and Zydeco most resemble the exuberant forró music, also accordion-driven, of the Brazilian northeast. There is always a party in that bayou music, and this film has a way of calling us to the party.

Concert films, by contrast, fall curiously flat much of the time. Projecting the illusion of a three-dimensional experience, in a nearly empty room, doesn’t take the place of being there. But since that is often not possible, we must settle for the document. The advantage posed by the collection Lightnin’ Hopkins, Rare Performances 1960-1979 is that we gain a different kind of depth, viewing him over time, in a variety of settings. Thus we may appreciate Hopkins’s irreducible qualities as a musician, his essential poetry and grace. First seen playing on the street and in a Houston bar, not long after his rediscovery, he seems already a master of timing and lyric economy. Later, he performs for folklorists in Seattle, then in a PBS studio concert, and finally on the show “Austin City Limits” where he has gone electric, enjoying his wah-wah pedal. He remains poised throughout, on slow burn but with a smile, always making those blues runs look so easy on his guitar.

Vestapol’s numerous anthology DVDs are likewise drawn from many sources, but Ramble to Cashel presents seven Celtic fingerstyle guitarists each in the same cold studio conditions. This may be just as well, for one of Vestapol’s aims is pedagogical; the footage here grants little distraction, so we may concentrate on watching formidable technique while listening to the prettiest tunes. Indeed, these musicians—Martin Simpson, Pierre Bensusan, Duck Baker, among them—mostly hunch over their instrument, often with eyes closed, like dervishes lost to a flame of their own making. Watching the finely worked-out fingerings, and the intricate embellishments to these traditional pieces, we get a sense of how very much work was involved to produce each little gem.

* * *

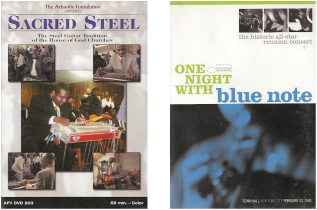

_Sacred Steel (Arhoolie)

One Night with Blue Note (Blue Note)

Folk Music of the Sahara: Among the Tuareg of Libya (Sublime Frequencies)

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 5/6 (2006)

If music is the next best thing to heaven, as the musicians and preachers in Sacred Steel suggest, they certainly make the proximity of the two sound convincing. Records give a good idea of the transcendent fervor at work in this music, but seeing and hearing its practitioners on video—performing their worship music at House of God Pentecostal church services in Florida and New York state—well nigh plunges us into the midst of the experience. When the music really gets rocking, it is easy to imagine that Jimi Hendrix or Albert Ayler would be right at home. This documentary does a satisfying job of tracing the style back to its beginnings in the 1930s as a wailing wild branch of gospel under the influence of the Hawaiian steel guitar, and each generation since has brought new artistry. The electric steel guitar players take off where the gospel singers flew highest, making the strings scream and moan and holler and testify, while the musician himself remains cool and collected, barely smiling.

For anyone who has ever been intoxicated by some of the classic Blue Note records of the 1950s and ‘60s, One Night with Blue Note reunifies many of the principles for a landmark concert at Town Hall in New York, in February 1985, an event that helped relaunch the label under new ownership. The fleet-footed lenswork of the cameramen gets us up close and personal, so that we really get to ogle the fingers and hands and heads engaged in the music making. The evening boasts a remarkable roster of artists, grouped into varying formations: among them, Hubbard, Henderson, Hancock, Hutcherson, Blakey, Tyner, McLean, Lou Donaldson, Jimmy Smith, Stanley Turrentine, to close with a solo by Cecil Taylor. This is a sublime document, the concert blocked out with period photos from when the musicians first recorded for Blue Note, and punctuated by shots of many of the classic album covers: a small pinch of time, some twenty or more years since its conception (plus the twenty years now since the concert), and the music hasn’t aged.

Ancient as the traditions may be in Folk Music of the Sahara: Among the Tuareg of Libya, the ethnographic impulse in viewing them is quietly subverted. Literally, for there is no voice-over narration, no text except for the couple pages in the accompanying booklet, to explain to us what we are seeing. Nonetheless, the camera brings us right into the thick of things: among the beautifully ornamented crowds and among the veiled musicians, mostly on frame drums and the double-reed rhaita, and even inside the women’s quarters with their group singing. Filmed in the desert oasis town of Ghadames, an old trans-Saharan trading post for Tuareg camel caravans in western Libya near the borders of Tunisia and Algeria, the music and dance sequences follow without our ever learning how we landed there, nor where we are exactly, nor what is the occasion. While it lasts, though, we watch as if in a marvelous dream, wordlessly slipping away into another life entirely.

* * *

One Night with Blue Note (Blue Note)

Folk Music of the Sahara: Among the Tuareg of Libya (Sublime Frequencies)

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 5/6 (2006)

If music is the next best thing to heaven, as the musicians and preachers in Sacred Steel suggest, they certainly make the proximity of the two sound convincing. Records give a good idea of the transcendent fervor at work in this music, but seeing and hearing its practitioners on video—performing their worship music at House of God Pentecostal church services in Florida and New York state—well nigh plunges us into the midst of the experience. When the music really gets rocking, it is easy to imagine that Jimi Hendrix or Albert Ayler would be right at home. This documentary does a satisfying job of tracing the style back to its beginnings in the 1930s as a wailing wild branch of gospel under the influence of the Hawaiian steel guitar, and each generation since has brought new artistry. The electric steel guitar players take off where the gospel singers flew highest, making the strings scream and moan and holler and testify, while the musician himself remains cool and collected, barely smiling.

For anyone who has ever been intoxicated by some of the classic Blue Note records of the 1950s and ‘60s, One Night with Blue Note reunifies many of the principles for a landmark concert at Town Hall in New York, in February 1985, an event that helped relaunch the label under new ownership. The fleet-footed lenswork of the cameramen gets us up close and personal, so that we really get to ogle the fingers and hands and heads engaged in the music making. The evening boasts a remarkable roster of artists, grouped into varying formations: among them, Hubbard, Henderson, Hancock, Hutcherson, Blakey, Tyner, McLean, Lou Donaldson, Jimmy Smith, Stanley Turrentine, to close with a solo by Cecil Taylor. This is a sublime document, the concert blocked out with period photos from when the musicians first recorded for Blue Note, and punctuated by shots of many of the classic album covers: a small pinch of time, some twenty or more years since its conception (plus the twenty years now since the concert), and the music hasn’t aged.

Ancient as the traditions may be in Folk Music of the Sahara: Among the Tuareg of Libya, the ethnographic impulse in viewing them is quietly subverted. Literally, for there is no voice-over narration, no text except for the couple pages in the accompanying booklet, to explain to us what we are seeing. Nonetheless, the camera brings us right into the thick of things: among the beautifully ornamented crowds and among the veiled musicians, mostly on frame drums and the double-reed rhaita, and even inside the women’s quarters with their group singing. Filmed in the desert oasis town of Ghadames, an old trans-Saharan trading post for Tuareg camel caravans in western Libya near the borders of Tunisia and Algeria, the music and dance sequences follow without our ever learning how we landed there, nor where we are exactly, nor what is the occasion. While it lasts, though, we watch as if in a marvelous dream, wordlessly slipping away into another life entirely.

* * *

_Jazz Icons on DVD

Louis Armstrong, Live in ‘59

Dizzy Gillespie, Live in ‘58 & ‘70

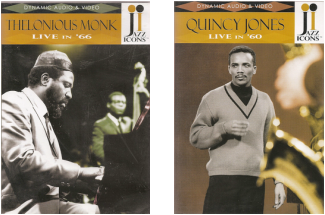

Thelonious Monk, Live in ‘66

Quincy Jones, Live in ‘60

written in Fall 2006 for Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 7/8, but the journal ceased publication

Launched last year with nine titles, the Jazz Icons series presents rare full-length concerts by jazz masters of the postwar decades. More than filmed documents, these performances grant us fuller access to the music: viewing Louis Armstrong with his all stars (trombonist Trummy Young, clarinetist Peanuts Hucko) in Belgium, for instance, offers a glimpse of what sent Julio Cortázar over the moon several years earlier on seeing Armstrong in Paris (“Louis enormísimo cronopio”). Above all here, he wins the audience by his understated prowess as a vocalist—his acute if casual timing, the expressiveness of his eyes and hands, each phrase (even scat) drenched in nuance. His classic versions of “C’est Si Bon” and “Mack the Knife” are thus worth seeing not just for the luminous smile but for his evident delight in delivering the lyrics. And of course his spirit animates the band: the players sparkle together, even in a tune they must have done a thousand times, the madcap “Tiger Rag.” It helps to see with our eyes why Armstrong’s style remains among the pinnacles of jazz.

On the first of the two Dizzy Gillespie dates, Belgium 1958, Sonny Stitt gives a masterful performance, playing both alto sax (“Loverman”) and tenor (“Blues Walk”). It is instructive to watch how he holds his horn, how he stands and breathes, as he delivers his long solos brimming with bluesy flourishes. Dizzy himself is pure concentration and cool, but also bemusement: he has a whale of a time singing “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” in a grinning duet with Stitt. On the 1970 date in Copenhagen, a tight and exuberant session, he is featured soloist and guest director of the 16-piece Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band (with Ronnie Scott, Sahib Shihab, and Tony Coe in its roster). Seeing his comfort talking to the audience, goofing with children, one could almost forget (while they’re at rest) the high artistry of the players. Dizzy’s own solos are intricate and flawless, and he clearly digs the band. The musicians themselves put forth a potent and vibrant sound, all the more when given full lungs as in “Manteca,” as they in turn celebrate his music.

What a treat to see Thelonious Monk’s quartet performing in Oslo and Copenhagen in 1966. Through many close-ups of the keyboard, we can better appreciate Monk’s singular approach to playing the piano—the percussive attack that lends a world of melodic emphases, his unexpectedly fertile use of cross-handed technique, the way he never crowds the sound but renders a selective few notes at any moment into an inimitable chemistry. And then there is his famous little dance, each time he lays out while another musician solos he rises from his seat and turns not so much to face them as to respond, to listen, by way of his steps, right elbow swinging out in time with the music; on every tune the dance materializes, except during his solo version of “Don’t Blame Me” when it’s Ben Riley who briefly sketches a playful imitation of Monk’s dance. Curious to note how seldom the bandmembers bother to make eye contact with each other: intuition dictates, the ear knows, Monk’s cues are all in the timing, how he propels each part of the tune forward. No doubt this is the schoolhouse and the lessons abound.

The only visual documents from the legendary 1960 tour of Quincy Jones’s 18-piece dream band (Clark Terry, Phil Woods, Jerome Richardson, Julius Watkins, Melba Liston . . . ), these concerts in Belgium and Switzerland reveal a highly polished, powerhouse ensemble. Though still in his 20s, Jones was already much in demand as an arranger and bandleader, and his smooth confidence in drawing the best from his players is noteworthy here. Their vagabond 10-month tour throughout the continent was planned on the fly, at the last minute, only after they were stranded in Paris following the early closing of the Harold Arlen musical Free and Easy that had brought them over. With a book that included jazz standards (“Moanin’,” “Parisian Thoroughfare,” “Everybody’s Blues”) and Jones originals (“Birth of a Band”), this group must have lit up the sky everywhere they went.

Louis Armstrong, Live in ‘59

Dizzy Gillespie, Live in ‘58 & ‘70

Thelonious Monk, Live in ‘66

Quincy Jones, Live in ‘60

written in Fall 2006 for Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 7/8, but the journal ceased publication

Launched last year with nine titles, the Jazz Icons series presents rare full-length concerts by jazz masters of the postwar decades. More than filmed documents, these performances grant us fuller access to the music: viewing Louis Armstrong with his all stars (trombonist Trummy Young, clarinetist Peanuts Hucko) in Belgium, for instance, offers a glimpse of what sent Julio Cortázar over the moon several years earlier on seeing Armstrong in Paris (“Louis enormísimo cronopio”). Above all here, he wins the audience by his understated prowess as a vocalist—his acute if casual timing, the expressiveness of his eyes and hands, each phrase (even scat) drenched in nuance. His classic versions of “C’est Si Bon” and “Mack the Knife” are thus worth seeing not just for the luminous smile but for his evident delight in delivering the lyrics. And of course his spirit animates the band: the players sparkle together, even in a tune they must have done a thousand times, the madcap “Tiger Rag.” It helps to see with our eyes why Armstrong’s style remains among the pinnacles of jazz.

On the first of the two Dizzy Gillespie dates, Belgium 1958, Sonny Stitt gives a masterful performance, playing both alto sax (“Loverman”) and tenor (“Blues Walk”). It is instructive to watch how he holds his horn, how he stands and breathes, as he delivers his long solos brimming with bluesy flourishes. Dizzy himself is pure concentration and cool, but also bemusement: he has a whale of a time singing “On the Sunny Side of the Street,” in a grinning duet with Stitt. On the 1970 date in Copenhagen, a tight and exuberant session, he is featured soloist and guest director of the 16-piece Kenny Clarke-Francy Boland Big Band (with Ronnie Scott, Sahib Shihab, and Tony Coe in its roster). Seeing his comfort talking to the audience, goofing with children, one could almost forget (while they’re at rest) the high artistry of the players. Dizzy’s own solos are intricate and flawless, and he clearly digs the band. The musicians themselves put forth a potent and vibrant sound, all the more when given full lungs as in “Manteca,” as they in turn celebrate his music.

What a treat to see Thelonious Monk’s quartet performing in Oslo and Copenhagen in 1966. Through many close-ups of the keyboard, we can better appreciate Monk’s singular approach to playing the piano—the percussive attack that lends a world of melodic emphases, his unexpectedly fertile use of cross-handed technique, the way he never crowds the sound but renders a selective few notes at any moment into an inimitable chemistry. And then there is his famous little dance, each time he lays out while another musician solos he rises from his seat and turns not so much to face them as to respond, to listen, by way of his steps, right elbow swinging out in time with the music; on every tune the dance materializes, except during his solo version of “Don’t Blame Me” when it’s Ben Riley who briefly sketches a playful imitation of Monk’s dance. Curious to note how seldom the bandmembers bother to make eye contact with each other: intuition dictates, the ear knows, Monk’s cues are all in the timing, how he propels each part of the tune forward. No doubt this is the schoolhouse and the lessons abound.

The only visual documents from the legendary 1960 tour of Quincy Jones’s 18-piece dream band (Clark Terry, Phil Woods, Jerome Richardson, Julius Watkins, Melba Liston . . . ), these concerts in Belgium and Switzerland reveal a highly polished, powerhouse ensemble. Though still in his 20s, Jones was already much in demand as an arranger and bandleader, and his smooth confidence in drawing the best from his players is noteworthy here. Their vagabond 10-month tour throughout the continent was planned on the fly, at the last minute, only after they were stranded in Paris following the early closing of the Harold Arlen musical Free and Easy that had brought them over. With a book that included jazz standards (“Moanin’,” “Parisian Thoroughfare,” “Everybody’s Blues”) and Jones originals (“Birth of a Band”), this group must have lit up the sky everywhere they went.