Kagel’s Keys

published in Review: Latin American Literature and Arts _(New York) 62 (Spring 2001)

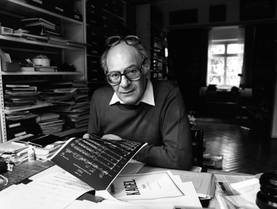

There is no single port of entry into the music of Mauricio Kagel. No tag or affiliation can prepare the listener who soon becomes immersed in the protean textures and the very spirit of inquiry that moves his work. Philosopher, metaphysician, provocateur, composing an extensive oeuvre of great diversity through five decades, Kagel incessantly questions the roles of tradition and performance in Western classical music. Along the way, he has challenged old habits and underscored the inherent theatricality of all music production, frequently crossing over to where music becomes theater, writing radio plays and making some twenty films as forms of his particular music theater.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1931, he worked at the Chamber Opera and conducted at the Teatro Colón before moving in 1957, on a German scholarship, to Cologne where he still lives. There he found a supportive environment and the resources to help nurture his expansive vision. He became a regular lecturer at the Darmstadt summer courses for new music, was later guest professor of composition at the university in Buffalo, and in 1969 succeeded Stockhausen as director of the Cologne new music courses; since 1974, he has been Professor of Contemporary Music Theater at the city’s Musikhochschule.

Few of Kagel’s works show any discernible trace of his cultural origins. Rather, his perspective in music recalls that of Borges, regarding the Argentine writer and tradition: of the West and somehow still outsiders, they allow themselves free range over all of Western culture, borrowing where they please, drawing from it according to their lights. Kagel approaches music almost like a scientist, with his investigations into the relationships of sounds and his sort of programmed anti-program as a method for subverting expectations, yet he has always taken care to build into his pieces the crucial element of indeterminacy. He refuses finality in the realization of his scores, devising complex and adaptable structures so that performing the music remains a fresh experience.

If one were to generalize about the trajectory of Kagel’s output, it might be said that he has grown more melodic, his phrases given more development; increasingly, traditional notions of beauty in music are left partially intact, albeit transformed. His later work sounds more classical, in a modernist way, whereas in the 1950s and 1960s he tended toward abstraction, favoring a vanguard pointillism with an emphasis on extended instrumental techniques, in the pursuit of an absolute music. Yet to hear side by side certain pieces written nearly forty years apart---Transición II for piano, percussion and tapes (1958-9) and Auftakte, sechshändig for piano and percussion (1996), on Serenade: chamber works (cpo); or Metapièce [Mimetics] (1961) and À deux mains (1995), both for piano, on Solowerke (Winter & Winter)---the differences seem small, as though Kagel had maintained a remarkable consistency in his sound. Indeed, the later pieces do not abandon the conceptual grounding of his earlier work, even as they incorporate the experiments of intervening years: there is still the penchant for thinking in episodes of discontinuous materials, the close attention to tone colors, and the urge to give form to “impromptu musicality.”

The contrast in Kagel’s string quartets---performed by the impeccable Arditti Quartet on Mauricio Kagel I (Naïve Montaigne; the label has devoted eight records to the composer)---offers another angle on the maturing of radical departures. String Quartet I and II (1965-67), each written as a single movement, employ extreme techniques to explode the genre. Amid the strange syntax of noises few actual notes surface, and those are seldom executed by conventional means. He calls for props to “prepare” the instruments (knitting needles, paper clips, strips of paper), poses obstacles (a left-hand glove on the first violinist in one passage), and cues the musicians with elaborate and enigmatic stage directions in his score. What emerges from all this high absurdity is a finely wrought piece of music that articulates its own dramatic tension. Two decades later, the wily and majestic String Quartet III (1986-87) practically overflows with thematic motifs that weave through the four movements, at times obliquely, in a harmonic palette reminiscent of Bartok’s quartets. However, the abrupt shifts of tempo and mood creating a montage of events, and the wide array of instrumental techniques (without external objects), unite this work with his practice in earlier pieces. Here too he makes use of dramatic cues, as less overt theater, to direct the interactions of the musicians among themselves.

Around 1970, Kagel began to focus on musical and political history in his work and the mysteries of cultural reference. Exotica (Koch Schwann), from 1970-71, takes another radical turn by considering that elusive border between the West and the world beyond. Six performers play a host of non-European instruments (wind, string, percussion) from four continents, thus raising questions: How to hear these sounds? What place does irony have in their portrayal? What is authentic, especially where tapes of genuine non-European music are also played? The composer himself asks: “Is the resulting music 'exotic' because it has been reshaped by the pen of a Western composer, or is it more that, with instruments of this kind, it’s not possible to produce music with typical Western features?” The performers are given prescribed rhythms with dynamics and duration, for which they must furnish the pitches, and the score’s five sections can be played in any order; the choice of which instruments to use at a specific moment is often left to the players, with a preference for vocal parts. The piece is like a journey to no place, or to many places at once, by way of sounds both strange and familiar.

Especially through the 1970s and 1980s, Kagel’s method often involved appropriating some materials---collecting motifs, qualities of sounds, structural ideas---in order to de-compose and reconstruct them. In 1898 (Deutsche Grammophon), from 1972-73, for chamber ensemble, his goal was “to convey a musical X-ray of the end of the 19th century.” The title refers to the year of the first recording technique, the dawn of modernism as it were, “a time where one inhales tonally, and exhales atonally.” Here he sought “to effect a compositional reconstruction of the sound of the first, acoustically unstable recordings”; to this end, he had a mutant family of string instruments built, based on the Stroh-violin of the time (invented for greater amplification in recording), wherein the body of the instrument was replaced or adapted with a simple pick-up system connected to a trumpet bell. Redefining “the treatment of timbre,” he decided to forgo harmonic complexity in favor of unison lines and a layering of octaves. Enhancing the dramatic nuance and even setting the tone on occasion, as in the eerie cascading phrases at the end, are the untrained voices of twenty-two schoolchildren whose laughter, crying, panting, and other sounds seem like so many signals from a world of ghosts, a fleeting moment of imminence.

But Kagel is not a mystic or a sentimentalist: he is too attracted to the substance of illusion, how music itself creates space, gesture, memory. There is always a double edge in his outlook, a penchant for play, irony. In Variété (Mauricio Kagel 4, Naïve Montaigne), from 1976-77, for six instruments, he explores a sort of implicit theatre: “a concert/show combining a number of musical idioms associated with the traditional vaudeville style,” a “théâtre trouvé” where “new pieces of music, not bound to any particular visual content, are confronted by other presentation.” That visual element remains unspecified but may, he suggests, feature “illusionists, jugglers, magicians, acrobats, striptease artists” or many other possible performers upon the shifting stage of the work’s eleven parts. Above all, the music’s scenic evocations---in the spirit of Milhaud, Weill, even Nino Rota---almost insist on an imagined choreography, but where the lightness is constantly shadowed.

Much of Kagel’s music has entailed working in series, composition as an ongoing reflection upon a set of problems, a puzzle of language, the turning of a cultural moment. Into these works he manages to compress many levels, and certain forms of organization seem particularly inspired. Rrrrrrr . . . (1981) consists of 41 separate pieces of music, all beginning with the letter R. “I got hold of a paperback edition of a music dictionary,” he explains, “and immediately found myself in the midst of infinitely multiplying domains, ranging from compelling semantics to the farthest reaches of musical poesy.” The eight pieces for organ (Rrrrrrr . . . , Koch Swann), with their incredible breadth of styles and musical figures, render the full sumptuous potential of the instrument, notably in “Raga,” “Ragtime,” and “Rosalie.” Curiously, when four of the organ pieces are adapted for accordion, on Solowerke, that instrument seems rarely to have been so expressive. The five pieces for jazz ensemble from Rrrrrrr . . . , on Mauricio Kagel 2, likewise command a range of styles, but as though fashioning an amalgam of different moments in jazz.

The accumulation and transformation of texts, an organizing principle in certain works, is placed right at the core of compositions like Sankt-Bach-Passion (Mauricio Kagel 8), an oratorio from 1985 for soloists, choirs, and large orchestra, based on the life of Bach, and >>. . . den 24.xii.1931<< (Mauricio Kagel 3), from 1988-91, for baritone and instruments, which lays out a series of news events all related to the date of his birth. As in his earlier meditations on Beethoven and Stravinsky, treating the historical figure as well as the music, Kagel sought “an open transfer of musical languages without stylistic impediments” in his work on Bach. Developing a technique of “meta-collage,” he borrows and transposes, following Bach’s lead. But remarkable as any of the musical effects he achieves is the great plasticity he finds in the texts, culled from many sources and resourcefully edited to dramatize the story of Bach’s own struggles. >>. . . den 24.xii.1931<<, a piece utterly propelled by the choice of texts, starts out from the ambiguity of such a birth date, Christmas eve, to consider, in sequence, the chance coincidence of an Argentine prison revolt, the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, a Nazi ad for cigarettes, a disaster at the Vatican library, and instances of longing and exile felt at such a time of year.

Given his multidirectional perspective, even Kagel’s musical observations on place are complicated affairs. In the eight-piece cycle for salon orchestra, The Compass Rose, from 1988-94, five of which are heard on Mauricio Kagel 5 (Stücke der Windrose), he set out to survey cultural evocations of the different points on the compass. But, as he notes, being from the Southern hemisphere “the four cardinal points evoke particular experiences . . . exactly contrary to the corresponding emotional world of Europeans.” Again he achieves a sort of amalgam of viewpoints, changing his own imaginary locale with each piece, so that the meanings of East, South, Northwest, keep mutating before our ears. The music is playfully sublime, and on this stage endlessly turning he pays special attention to the American and Transatlantic distances that he has known (“North-East,” a musical “reflection on South America,” is dedicated to Alejo Carpentier).

Nah und Fern [Near and Far] (Mauricio Kagel 7), by contrast, a radio piece for bells and trumpets with background, from 1993-94, focuses on a much more specific place---or at least concurrent versions of a place. The piece grew out of his Melodies for Carillon and his fascination with the bells at the DomKerk in Utrecht. Hearing the bells ringing in the immediate vicinity drew his attention both to the ambient noises (traffic, footsteps, the cogwheel mechanism of the carillon) and to the relative definitions of “near” and “far” with respect to the sound of the bells. All this, a polyphony of impressions, he mixed in the studio with two earlier pieces for trumpets to produce an experience whose reality seems indisputable. For Kagel, it was a way of taking an old tradition, the bells, into the future.

* * *

A wonderful film was made on Kagel's return to Buenos Aires in 2006, after a thirty-year absence. Süden (2008; available from www.kairos-music.com), director Gastón Solnicki's debut feature, follows the composer as he rehearses the Ensamble Süden (founded by Argentine musicians to perform his work) in preparation for the Festival Kagel at the Teatro Colón. A poet-philosopher to the core, his advice to the musicians along the way is every bit as illuminating as the music.