Julio Cortázar

published in part in the Los Angeles Times (August 28, 1983), in full in the Paris Review (New York) 26:93 (Fall 1984), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: Interviews in Paris with Uncommon Writers (Iowa City: Iowa, 1991) as well as the anthology Critical Essays on Julio Cortázar, ed. Jaime Alazraki (New York: G. K. Hall, 1999)

When Julio Cortázar died of cancer in February, 1984, at the age of sixty-nine, the Madrid newspaper El País hailed him as one of the Spanish-speaking world’s great writers and over two days carried eleven full pages of tributes, reminiscences, and farewells.

Though Cortázar had lived in Paris since 1951, he visited his native Argentina regularly until he was officially exiled in the early 1970s by the military junta, who had taken exception to several of his short stories. With the victory in late 1983 of the democratically elected Alfonsín government, Cortázar was able to make one last visit to his home country and to see his mother. Alfonsín’s culture minister chose to give him no official welcome, afraid that his political views were too far to the left, but the writer was nonetheless greeted as a returning hero. One night in Buenos Aires, coming out of a movie theater after seeing the new film based on Osvaldo Soriano’s novel No Habrá Más Pena Ni Olvido (A Funny, Dirty Little War), Cortázar and his friends ran into a student demonstration coming toward them, which instantly broke file on glimpsing the writer and crowded around him. The bookstores on the boulevards still being open, the students hurriedly bought up copies of Cortázar’s books so that he could sign them. A kiosk salesman, apologizing that he had no more of Cortázar’s books, held out a Carlos Fuentes novel for him to sign.

Cortázar was born in Brussels in 1914. When his family returned to Argentina after the war, he grew up in Banfield, not far from Buenos Aires. He took a degree as a schoolteacher and went to work in a town in the province of Buenos Aires until the early 1940s, writing for himself on the side. One of his first published stories, “House Taken Over,” which came to him in a dream, appeared in 1946 in a magazine edited by Jorge Luis Borges, though they seldom met since. It wasn’t until after Cortázar moved to Paris in 1951, however, that he began publishing in earnest. In Paris, he worked as a translator and interpreter for UNESCO and other organizations. Writers he translated included Poe, Defoe, and Marguerite Yourcenar. In 1963, his second novel, Hopscotch, about an Argentine’s existential and metaphysical searches in Paris and Buenos Aires amid jazz-filled nights, really established Cortázar’s name.

Though he is known above all as a modern master of the short story, Cortázar’s four novels demonstrated a ready innovation of form while exploring basic questions about the individual in society. At the same time, his indomitable playfulness reached its highest expression in the novels. These include The Winners (1960), 62: A Model Kit (1968), based in part on his experience as an interpreter, and A Manual for Manuel (1973), about the kidnapping of a Latin American diplomat. Whatever propels him in the different novels, the life within them is a dizzy enchantment.

But it was Cortázar’s many stories that most directly claimed his fascination with the fantastic. His most well-known story was the starting point for Antonioni's film Blow-Up. Just before he died, a travel journal was published, Los Autonautas de la Cosmopista, on which he collaborated with his wife, Carol Dunlop, during a voyage from Paris to Marseille in a camping van. Published simultaneously in Spanish and French, Cortázar signed all author’s rights and royalties over to the Sandinista government in Nicaragua; the book soon became a best-seller. Two posthumous collections of his political articles on Nicaragua and on Argentina have also been published.

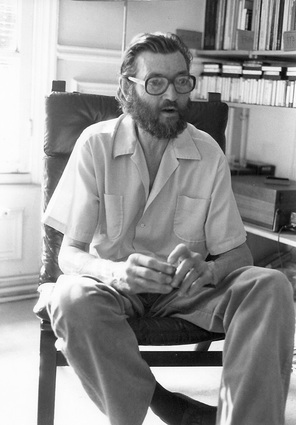

This interview took place at Cortázar’s home in Paris on July 8, 1983. A few months earlier, his wife had died of cancer; she was thirty years younger than him. Home for barely a week from his extensive travels, he sat in his favorite chair, smoking his pipe, near the thousands of records that filled the shelves from floor to ceiling.

In some of the stories in your most recent book, Deshoras, it seems the fantastic is entering into the real world more than ever. Have you yourself felt that, as if the fantastic and the commonplace are becoming one almost?

Yes, in these recent stories I have the feeling that there is less distance between what we call the fantastic and what we call the real. In my older stories the distance was greater because the fantastic was really very fantastic, and sometimes it touched on the supernatural. Well, I am glad to have written those older stories, because I think the fantastic has that quality to always take on metamorphoses, it changes, it can change with time. The notion of the fantastic we had in the epoch of the gothic novels in England, for example, has absolutely nothing to do with our notion today. Now we laugh when we read about the castle of Otranto—the ghosts dressed in white, the skeletons that walk around making noises with their chains. And yet that was the notion of the fantastic at the time. It’s changed a lot. I think my notion of the fantastic, now, more and more approaches what we call reality. Perhaps because for me reality also approaches the fantastic more and more.

Much more of your time in recent years has gone to the support of various liberation struggles in Latin America. Hasn’t that too helped bring the real and the fantastic closer for you? As if it’s made you more serious.

Well, I don’t like the idea of “serious.” Because I don’t think I am serious, in that sense at any rate, where one speaks of a serious man or a serious woman. These last few years all my efforts concerning certain Latin American regimes—Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and now above all Nicaragua—have absorbed me to such a point that even the fantastic in certain stories dealing with this subject is a fantastic that’s very close to reality, in my opinion. So, I feel less free than before. That is, thirty years ago I was writing things that came into my head and I judged them only by esthetic criteria. Now, I continue to judge them by esthetic criteria, because first of all I’m a writer, but I’m a writer who is very tormented, preoccupied by the situation in Latin America. Very often that slips into my writing, in a conscious or in an unconscious way. But in Deshoras, despite the stories where there are very precise references to ideological and political questions, I think my stories haven’t changed. They’re still stories of the fantastic.

The problem for an engagé writer, as they call it now, is to continue being a writer. If what he writes becomes simply literature with a political content, it can be very mediocre. That’s what has happened to a number of writers. So, the problem is one of balance. For me, what I do must always be literature, the highest I can do. To go beyond the possible, even. But, at the same time, very often to try to put in a charge of contemporary reality. And that’s a very difficult balance.

But are you looking to mix the two?

No. Before, the ideas that came to me for stories were of the purely fantastic, while now many ideas are based on the reality of Latin America. In Deshoras, for example, the story about the rats, “Satarsa,” is an episode based on the reality of the fight against the Argentine guerrilleros. The problem is to put it in writing, because one is tempted all the time to let oneself keep going on the political level alone.

What has been the response to such stories? Was there much difference in the response you got from literary people as from political people?

Of course. The bourgeois readers in Latin America who are indifferent to politics or else who even align themselves with the right wing, well, they don’t worry about the problems that worry me—the problems of exploitation, of oppression, and so on. Those people regret that my stories often take a political turn. Other readers, above all the young, who share with me these sentiments, this need to struggle, and who love literature, love these stories. For example, “Apocalypse at Solentiname” is a story that Nicaraguans read and reread with great pleasure. And the Cubans read “Meeting” with lots of pleasure as well.

What has determined your increased political involvement in recent years?

The military in Latin America, they’re the ones who make me work harder. If they get out, if there were a change, then I could rest a little and work on poems and stories that are exclusively literary. But it’s they who give me work to do. The more they are there, the more I must be against them.

You have said various times that for you literature is like a game. In what ways?

For me literature is a form of play. It makes up part of what they call the ludic side of man, homo ludens. But I’ve always added that one must be careful, because there are two forms of play. There’s football, for example, which is a game. And there are games that are very profound and very serious, all while being games. One must consider that when children play, you only have to look at them, they take it very seriously. They’re amusing themselves, but playing is important for them, it’s their main activity. Just as when they’re older, for example, it will be their erotic activity. When they’re little, playing is as serious as love will be ten years later. I remember when I was little, when my parents came to say, “Okay, you’ve played enough, come take a bath now,” I found that completely idiotic, because for me the bath was a silly matter. It had no importance whatsoever, while playing with my friends, that, was something serious. And for me literature is like that, it’s a game but a game where one can put one’s life, one can do everything for that game.

What interested you about the fantastic in the beginning, were you very young?

Oh yes. It began with my childhood. I was very surprised when I was going to grade school, that most of my young classmates had no sense of the fantastic. They were very realistic. They took things as they were . . . that is a plant, that is an armchair. And I was already seeing the world in a way that was very changeable. For me things were not so well defined in that way, there were no labels. My mother, who is a very imaginative woman, helped me a lot. Instead of telling me, “No, no, you should be serious,” she was pleased that I was very imaginative, and when I turned toward the world of the fantastic, she helped me because she gave me books to read. That’s how at the age of nine I read Edgar Allan Poe for the first time. That book I stole to read because my mother didn’t want me to read it, she thought I was too young and she was right. The book scared me and I was ill for three months, because I believed in it--dur comme fer, as the French say. For me the fantastic was perfectly natural. When I read a story of the fantastic, I had no doubts at all. That's the way things were. When I gave them to my friends, the’d say, “But no, I prefer to read cowboy stories.” Cowboys especially at the time. I didn’t understand that. I preferred the world of the supernatural, of the fantastic.

When you translated Poe’s complete works many years later, did you discover new things for yourself from so close a reading?

Many, many things. To begin with, I explored his language, which is highly criticized by the English and the Americans because they find it too baroque, in short they’ve made all sorts of reproaches. Well, since I’m neither English nor American, I see it with another perspective. I know there are aspects which have aged a lot, that are exaggerated, but that hasn’t the least importance next to his genius. To write, in those times, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” that takes an extraordinary genius. To write “Ligeia” or “Berenice,” or “The Black Cat,” any of them, shows a true genius for the fantastic and the supernatural. I should say, in passing, that yesterday I went to a friend’s house on the rue Edgar Allan Poe. There is a plaque where it says, “Edgar Poe, English writer.” He wasn’t English at all! I wanted to point that out because they should change the plaque. We’ll both protest!

In your own writing, besides the fantastic, there is a real warmth and affection for your characters as well.

Certain readers and certain critics have told me that too. That when my characters are children and adolescents, I have a lot of tenderness for them, which is true. I treat them with a lot of love. I think they are very alive in my novels and stories. When I write a story where the character is an adolescent, I am the adolescent while I write it.

Are many of your characters based on people that you’ve known?

I wouldn’t say many, but there are a few. Very often there are characters who are a mixture of two or three people. I have put together female characters from two women I had known. It gave the character in the story or the book a personality that was more complex, more difficult, because she had different ways of being that came from two women.

As with La Maga in Hopscotch?

Well, she is based on one woman, with a lot of psychological characteristics that are completely imaginary. I don’t need to depend on reality to write real things. I invent them, and they become real in the writing. Very often I’m amused because literary critics, especially those who are a bit academic, think that writers don’t have any imagination. They think a writer has always been influenced by this, this and this. They retrace the whole chain of influences. Influences do exist, but these critics forget one thing, that is the pleasure of inventing, pure invention. I know my influences. Edgar Allan Poe is an influence that is very present in certain of my stories. But the rest, it’s I who invent.

Is it when you feel the need to thicken a character that you mix two together? How does that happen?

Things don’t work like that. It’s the characters who direct me. That is, I see a character, he’s there, and I recognize someone I knew or occasionally two who are a bit mixed together, but that stops there. After, the character acts on his own account. He says things. . . I never know what they’re going to say when I’m writing dialogues. Really, it’s among them. Me, I’m typing out what they’re saying. And sometimes I burst out laughing, or I throw out a page because I say, “There you’ve said silly things. Out.” And I put in another page and start again with the dialogue, but there is no fabrication on my part. Really, I don’t fabricate anything.

So it’s not the characters you’ve known that impel you to write?

Not at all, no. Often I have the idea for a story, where there aren’t any characters yet. I’ll have a strange idea: something’s going to happen in a house in the country. I’m very visual when I write, I see everything. So, I see this house in the country and then abruptly I begin to situate the characters. It’s at that point that one of the characters might be someone I knew. But it’s not for sure. In the end, most of my characters are invented. Well, there is myself, there are many autobiographical references in the character of Oliveira in Hopscotch. It’s not me, but there’s a lot of me. Of me here in Paris, in my bohemian days, my first years here. But the readers who read Oliveira as Cortázar in Paris would be mistaken. No, no, I was very different.

Does what you write ever approach too closely the autobiographical?

I don’t like autobiography. I will never write my memoirs. Autobiographies of others interest me, but not my own. Very often, though, when I have ideas for a novel or a story, there are moments of my life, situations, that come very naturally to place themselves there. In the story “Deshoras,” the boy who is in love with his pal’s sister, who is older than him, I lived that. There is a small part of it that’s autobiographical, but from there on, it’s the fantastic or the imaginary which dominates.

You have even written of the need for memoirs by Latin American writers. Why is it you don’t want to write your own?

If I wrote my autobiography, I would have to be truthful and honest. I can’t tell an imaginary autobiography. And so, I would be doing a historian’s job, self-historian, and that bores me. Because I prefer to invent, to imagine.

José Lezama Lima in Paradiso has Cemí saying that “the baroque . . . is what has real interest in Spain and Hispanic America.” Why do you think that is so?

I cannot reply as an expert. The baroque has been very important in Latin America, in the arts and in literature as well. The baroque can offer a great richness; it lets the imagination soar in all its spiraling directions, as in a baroque church with its decorative angels and all that, or in baroque music. But I distrust the baroque a little in Latin America. The baroque writers, very often, let themselves go too easily in writing. They write in five pages what one could very well write in one page, which would be better. I too must have fallen into the baroque because I am Latin American, but I have always had a mistrust of it. I don’t like turgid, voluminous sentences, full of adjectives and descriptions, purring and purring into the reader’s ear. I know it’s very charming, of course, very beautiful, but it’s not me. I’m more on the side of Jorge Luis Borges in that sense. He has always been an enemy of the baroque; he tightened his writing, as with pliers. Well, I write in a very different way than Borges, but the great lesson he gave me is one of economy. He taught me when I began to read him, being very young, that it wasn’t necessary to write these long sentences at the end of which there was some vague thought. That one had to try to say what one wanted to with economy, but with a beautiful economy. It’s the difference perhaps between a plant, which would be the baroque with its multiplications of leaves, it’s very beautiful, and a precious stone, a crystal—that for me is more beautiful still.

The lines are very musical in your writing. Do you usually hear the words as you’re writing them?

Oh yes, I hear them, and I know that in writing—if I’m launched on a story, I write very quickly, because after I can revise—I will never put down a word that is disagreeable to me. There are words I don’t like—not just crude words, those I use when I have to—the sound, the structure of the word displeases me. For example, all the words in juridical and administrative language, they are frequently present in literature. And I hardly ever use those words because I don’t like them.

No, I can’t imagine them in the spirit of your writing.

It’s a question of music, finally. I like music more than literature, I’ve said it many times, I repeat it again, and for me writing corresponds to a rhythm, a heartbeat, a musical pulsation. That’s my problem with translations, because translators of my books sometimes don’t realize that there is a rhythm, they translate the meaning of the words. And I need this swing, this movement that my lines have. Otherwise, the story doesn’t sound right. Above all, certain moments in the stories must be directed musically, because that’s how they give their true meaning. It’s not what they say, but how they say it.

But it’s difficult to be at the same time rhythmically musical and economical like a crystal.

Yes, it’s very difficult, of course. But then I think especially of certain musics that have succeeded in being like that. The best works of Johann Sebastian Bach have the economy with the greatest musical richness. And in a jazz solo, a real jazz solo, a Lester Young solo, for example, at that point there is all the freedom, all the invention, but there is the precise economy that starts and finishes. Not like the mediocre jazz musicians who play for three-quarters of an hour because they have nothing to say, for that I’m very critical of certain forms of contemporary jazz. Because they have nothing more to say, they keep filling up the space. Armstrong, or Ellington, or Charlie Parker only needed two or three minutes to do like Bach, exactly like Johann Sebastian Bach, and Mozart. Writing for me must be like that, a moment from a story must be a beautiful solo. It’s an improvisation, but improvisation involves invention and beauty.

How do you start with your stories? By any particular entry, an image?

With me stories and novels can start anywhere. But on the level of the writing, when I begin to write, the story has been turning around in me a long time, sometimes for weeks. But not in a way that’s clear; it’s a sort of general idea of the story. A house where there’s a red plant in one corner, and then I know that there’s an old man who walks around in this house, and that’s all I know. It happens like that. And then there are the dreams, because during that time my dreams are full of references and allusions to what is going to be in the story. Sometimes the whole story is in a dream. One of my first stories, it’s been very popular, “House Taken Over,” that was a nightmare I had. I got up like that and wrote it. But in general they are fragments of references. That is, my subconscious is in the process of working through a story. The story is being written inside there. So when I say that I begin anywhere, it’s because I don’t know what is the beginning or the end. I start to write and that is the beginning, finally, but I haven’t decided that the story has to start like that. It starts there and it continues. Very often I have no clear idea of the ending, I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s gradually, as the story goes on, that things become clearer and abruptly I see the ending.

So you are discovering the story while you are writing it?

That’s right. I discover it a bit while I am writing. There too is an analogy, I think, with improvisation in jazz. You don’t ask a jazz musician, “But what are you going to play?” He’ll laugh at you. He has simply a theme, a series of chords he has to respect, and then he takes his trumpet or his saxophone and he begins. But he hasn’t the slightest idea . . . it’s not a question of idea. They’re different internal pulsations. Sometimes it comes out well, sometimes it doesn’t. Me, I’m a bit embarrassed to sign my stories. The novels, no, because the novels I worked on a lot; there’s a whole architecture. My stories, it’s as if they were dictated to me a little, by something that is in me, but it’s not me who’s responsible. Well, it does appear they are mine even so, I should accept them!

Are there certain aspects of writing a story that always pose a problem for you?

In general, no, because as I was explaining, the story is already made somewhere inside me. So, it has its dimension, its structure, it’s going to be a very short story or a fairly long story, all that is as if decided in advance. But in recent years I’ve started to sense some problems. I reflect more in front of the page. I write more slowly. And I write in a way that’s more spare. Certain critics have reproached me for that, they’ve told me that little by little I’m losing that suppleness in my stories. I say what I want to, but with a greater economy of means. I don’t know if it’s for better or worse. In any case, it’s my way of writing now.

You were saying that with the novels there is a whole architecture. Does that mean working very differently?

The first thing I wrote in Hopscotch was a chapter that is found in the middle now. It’s the chapter where the characters put out a board to pass from one window to another (chapter 41). Well, I wrote that without knowing why I was writing it. I saw the characters, I saw the situation, it was in Buenos Aires. It was very hot, I remember, and I was next to the window with my typewriter. I saw this situation of a guy who’s trying to make his wife go across, because he’s not going himself, to go get some silly thing, some nails. It was totally ridiculous, in appearance. I wrote all that, which is long, forty pages, and when I finished I said to myself, “All right, but what have I done? Because that’s not a story. What is it?” And then I understood that I was launched on a novel but couldn’t continue. I had to stop there and write the whole section in Paris before. That is, the whole background of Oliveira, because when I wrote the chapter with the board, I was thinking of myself a little at that point. I saw myself as the character, Oliveira was very much me at that point. But to do a novel with that, I had to go backwards before I could continue.

You were in Buenos Aires at that point.

At that point, because after the whole book was written here. This chapter I wrote in Buenos Aires.

And you sensed right away that it was a novel.

I sensed right away that it would be the novel of a city. I wanted to put in the Paris I knew and loved there, in the first part. It would also be a novel about the relations among several characters, but above all the problems, the metaphysical searches of Oliveira, which were mine at the time. Because at that period I was totally immersed in esthetics, philosophy, and metaphysics. I was completely outside of history and politics. In Hopscotch there is no reference to questions of Latin America and its problems. It’s later I discovered that.

You’ve often said that it was the Cuban revolution that awakened you to that.

And I say it again.

Do you revise much when you write?

Very little. That comes from the fact that the thing has already been at work inside me. When I see the rough drafts of certain of my friends, where everything is revised, everything’s changed, moved around, there are arrows all over the place . . . no no no. My manuscripts are very clean.

What are your writing habits? Have certain things changed?

There’s one thing that hasn’t changed, that will never change, that is the total anarchy and the disorder. I have absolutely no method. When I feel like writing a story I let everything drop, I write the story. And sometimes when I write a story, in the month or two that follows I will write two or three stories. In general, it comes in series. Writing one leaves me in a receptive state, and then I catch another story. You see the sort of image I use, but it’s like that, where the story drops inside of me. But after, a year can go by where I write nothing of literature, nothing. I should say too that these last few years I have spent a good deal of my time at the machine writing political articles. The texts I’ve written about Nicaragua, that are distributed through the syndicated press agencies, everything I’ve written about Argentina, they have nothing to do with literature, they’re militant things.

Do you have preferred places for writing?

In fact, no. At the beginning, when I was younger and physically more resistant, here in Paris for example a large part of Hopscotch I wrote in cafes. Because the noise didn’t bother me and, on the contrary, it was a congenial place. I worked a lot there, I read or I wrote. But with age I’ve become more complicated. I write when I’m sure of having some silence. I can’t write if there’s music, that’s absolutely excluded. Music is one thing and writing is another. I need a certain calm; but, this said, a hotel, an airplane sometimes, a friend’s house, or here at home are places where I can write.

About Paris. What gave you the courage to pick up and move off to Paris when you did, more than thirty years ago?

Courage? No, it didn’t take much courage. I simply had to accept the idea that coming to Paris, and cutting the bridges with Argentina at that time, meant being very poor and having problems making a living. But that didn’t worry me. I knew in one way or another I was going to manage. Primarily I came because Paris, French culture on the whole, held a lot of attraction for me. I had read French literature with passion in Argentina. So, I wanted to be here and get to know the streets and the places one finds in the books, in the novels. To go through the streets of Balzac or of Baudelaire. It was a very romantic voyage. I was, I am, very romantic. I have to be rather careful when I write, because very often I could let myself fall into . . . I wouldn’t say bad taste, perhaps not, but a bit in the direction of an exaggerated romanticism. So, there’s a necessary control there, but in my private life I don’t need to control myself. I really am very sentimental, very romantic. I’m a tender person, I have a lot of tenderness to give. What I give now to Nicaragua, it’s tenderness. It is also the political conviction that the Sandinistas are right in what they’re doing and that they’re leading an admirable struggle. But it’s not only the political idea. There’s an enormous tenderness because it’s a people I love. As I love the Cubans, and I love the Argentines. Well, all that makes up part of my character, and in my writing I have had to watch myself. Above all when I was young, I wrote things that were tearjerkers. That was really romanticism, the roman rose. My mother would read them and cry.

Nearly all your writing that people know dates from your arrival in Paris. But you were writing a lot before, weren’t you? A few things had already been published.

I’ve been writing since the age of nine, right up through my whole adolescence and early youth. In my early youth I was already capable of writing stories and novels, which showed me that I was on the right path. But I didn’t want to publish. I was very severe with myself, and I continue to be. I remember that my peers, when they had written some poems or a small novel, searched for a publisher right away. And it was bad, mediocre, because it lacked maturity. I would tell myself, “No, you’re not publishing. You hang onto that.” I kept certain things, and others I threw out. When I did publish for the first time I was over thirty years old; it was a little before my departure for France. That was my first book of stories, Bestiario, which came out in ‘51, the same month I took the boat to come here. Before, I had published a little text called Los Reyes, which is a dialogue. A friend who had a lot of money, who did small editions for himself and his friends, had taken me and done a private edition. And that’s all. No, there’s another thing—a sin of youth—a book of sonnets. I published it myself, but with a pseudonym.

You are the lyricist of a recent album of tangos, Trottoirs de Buenos Aires. What got you started writing tangos?

Well, I am a good Argentine and above all a porteño—that is, a resident of Buenos Aires, because it’s the port. The tango was our music, I grew up in an atmosphere of tangos. We listened to them on the radio, because the radio started when I was little, and right away it was tangos and tangos. There were people in my family, my mother and an aunt, who played tangos on the piano and sang them. Through the radio we began to listen to Carlos Gardel and the great singers of the time. The tango became like a part of my consciousness and it’s the music that sends me back to my youth again and to Buenos Aires. So, I’m quite caught up in the tango. All while being very critical, because I’m not one of those Argentines who believe the tango is the wonder of wonders. I think that the tango on the whole, especially next to jazz, is a very poor music. It is poor but it is beautiful. It’s like those plants that are very simple, that one can’t compare to an orchid or a rosebush, but which have an extraordinary beauty in themselves. In recent years, as I have friends who play tangos here—the Cuarteto Cedrón are great friends, and a fine bandoneon player named Juan José Mosalini—we’ve listened to tangos, talked about tangos. Then one day a poem came to me like that, which perhaps could be set to music, I didn’t really know. And then, looking among unpublished poems, most of my poems are unpublished, I found some short poems which those fellows could set to music, and they did. But we’ve done the opposite experience as well. Cedrón gave me a musical theme, I listened to it, and I wrote the words. So I’ve done it both ways.

In the biographical notes in your books, it says you are also an amateur trumpet player. Did you play with any groups?

No. That’s a bit of a legend that was invented by my very dear friend Paul Blackburn, who died quite young unfortunately. He knew that I played the trumpet a little, for myself at home. So he would always tell me, “But you should meet some musicians to play with.” I’d say, “No,” as the Americans say, “I lack equipment.” I didn’t have the abilities; I was playing for myself. I would put on a Jelly Roll Morton record, or Armstrong, or early Ellington, where the melody is easier to follow, especially the blues which has a given scheme. I would have fun hearing them play and adding my trumpet. I played along with them . . . but it sure wasn’t with them! I never dared approach jazz musicians; now my trumpet is lost somewhere in the other room there. Blackburn put that in one of the blurbs. And because there is a photo of me playing the trumpet, people thought I really could play well. As I didn’t want to publish without being sure, with the trumpet it was the same. And that day never arrived.

Have you worked on any novels since A Manual for Manuel?

Alas no, for reasons that are very clear. It’s due to political work. For me a novel requires a concentration and a quantity of time, at least a year, to work tranquilly and not abandon it. And now, I cannot. A week ago, I didn’t know I would be leaving for Nicaragua in three days. When I return I won’t know what’s going to happen after. But this novel is already written. It’s there, it’s in my dreams. I dream all the time of this novel. I don’t know what happens in the novel, but I have an idea. As in the stories, I know that it will be something fairly long that will have elements of the fantastic, but not so much. It will be, say, in the genre of A Manual for Manuel, where the fantastic elements are mixed in, but it won’t be a political book either. It will be a book of pure literature. I hope that life will give me a sort of desert island, even if the desert island is this room, and a year, I ask for a year. But when these bastards—the Hondurans, the Somocistas, and Reagan—are in the act of destroying Nicaragua, I don’t have my island. I couldn’t begin to write, because I would be obsessed by that all the time. That demands top priority.

And it can be difficult enough as it is with the priorities of life versus literature.

Yes and no. It depends on what kind of priorities. If the priorities are like those I just spoke about, touching on the moral responsibility of an individual, I would agree. But I know many people who are always crying, “Oh, I’d like to write my novel, but I have to sell the house, and then there are the taxes, what am I going to do?” Reasons like, “I work in the office all day, how do you expect me to write?” Me, I worked all day at UNESCO and then I came home and wrote Hopscotch. When one wants to write, one writes. If one is condemned to write, one writes.

Do you work anymore as a translator or interpreter?

No, that’s over. I lead a very simple life. I don’t need much money for the things I like: records, books, tobacco. So now I can live from my royalties. They’ve translated me into so many languages that I receive enough money to live on. I have to be a little careful; I can’t go out and buy myself a yacht, but since I have absolutely no intention of buying a yacht . . .

Have you enjoyed your fame and success?

Ah, listen, I’ll say something I shouldn’t say because no one will believe it, but success is not a pleasure for me. I’m glad to be able to live from what I write, so I have to put up with the popular and critical side of success. But I was happier as a man when I was unknown, much happier. Now I can’t go to Latin America or to Spain without being recognized every ten yards, and the autographs, the embraces . . . It’s very moving, because they’re readers who are frequently quite young. I’m happy they like what I do, but it’s terribly distressing for me on the level of privacy. I can’t go to a beach in Europe; in five minutes there’s a photographer. I have a physical appearance that I can’t disguise; if I were small I could shave and put on sunglasses, but with my height, my long arms and all that, they recognize me from afar. On the other hand, there are very beautiful things: I was in Barcelona a month ago, walking around the gothic quarter one evening, and there was an American girl, very pretty, playing the guitar very well and singing. She was seated on the ground earning her living. She sang a bit like Joan Baez, a very pure, clear voice. There was a group of young people from Barcelona listening. I stopped to listen to her, but I stayed in the shadows. At a certain point, one of these young men who was about twenty, very young, very handsome, approached me. He had a cake in his hand. He said, “Julio, take a piece.” So I took a piece and ate it, and I told him, “Thanks a lot for coming up and giving that to me.” And he said to me, “But, listen, I give you so little next to what you’ve given me.” I said, “Don’t say that, don’t say that,” and we embraced and he went away. Well, things like that, that’s the best recompense for my work as a writer. That a boy or a girl come up to speak to you and to offer you a piece of cake, it’s wonderful. It’s worth the trouble of having written.

published in part in the Los Angeles Times (August 28, 1983), in full in the Paris Review (New York) 26:93 (Fall 1984), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: Interviews in Paris with Uncommon Writers (Iowa City: Iowa, 1991) as well as the anthology Critical Essays on Julio Cortázar, ed. Jaime Alazraki (New York: G. K. Hall, 1999)

When Julio Cortázar died of cancer in February, 1984, at the age of sixty-nine, the Madrid newspaper El País hailed him as one of the Spanish-speaking world’s great writers and over two days carried eleven full pages of tributes, reminiscences, and farewells.

Though Cortázar had lived in Paris since 1951, he visited his native Argentina regularly until he was officially exiled in the early 1970s by the military junta, who had taken exception to several of his short stories. With the victory in late 1983 of the democratically elected Alfonsín government, Cortázar was able to make one last visit to his home country and to see his mother. Alfonsín’s culture minister chose to give him no official welcome, afraid that his political views were too far to the left, but the writer was nonetheless greeted as a returning hero. One night in Buenos Aires, coming out of a movie theater after seeing the new film based on Osvaldo Soriano’s novel No Habrá Más Pena Ni Olvido (A Funny, Dirty Little War), Cortázar and his friends ran into a student demonstration coming toward them, which instantly broke file on glimpsing the writer and crowded around him. The bookstores on the boulevards still being open, the students hurriedly bought up copies of Cortázar’s books so that he could sign them. A kiosk salesman, apologizing that he had no more of Cortázar’s books, held out a Carlos Fuentes novel for him to sign.

Cortázar was born in Brussels in 1914. When his family returned to Argentina after the war, he grew up in Banfield, not far from Buenos Aires. He took a degree as a schoolteacher and went to work in a town in the province of Buenos Aires until the early 1940s, writing for himself on the side. One of his first published stories, “House Taken Over,” which came to him in a dream, appeared in 1946 in a magazine edited by Jorge Luis Borges, though they seldom met since. It wasn’t until after Cortázar moved to Paris in 1951, however, that he began publishing in earnest. In Paris, he worked as a translator and interpreter for UNESCO and other organizations. Writers he translated included Poe, Defoe, and Marguerite Yourcenar. In 1963, his second novel, Hopscotch, about an Argentine’s existential and metaphysical searches in Paris and Buenos Aires amid jazz-filled nights, really established Cortázar’s name.

Though he is known above all as a modern master of the short story, Cortázar’s four novels demonstrated a ready innovation of form while exploring basic questions about the individual in society. At the same time, his indomitable playfulness reached its highest expression in the novels. These include The Winners (1960), 62: A Model Kit (1968), based in part on his experience as an interpreter, and A Manual for Manuel (1973), about the kidnapping of a Latin American diplomat. Whatever propels him in the different novels, the life within them is a dizzy enchantment.

But it was Cortázar’s many stories that most directly claimed his fascination with the fantastic. His most well-known story was the starting point for Antonioni's film Blow-Up. Just before he died, a travel journal was published, Los Autonautas de la Cosmopista, on which he collaborated with his wife, Carol Dunlop, during a voyage from Paris to Marseille in a camping van. Published simultaneously in Spanish and French, Cortázar signed all author’s rights and royalties over to the Sandinista government in Nicaragua; the book soon became a best-seller. Two posthumous collections of his political articles on Nicaragua and on Argentina have also been published.

This interview took place at Cortázar’s home in Paris on July 8, 1983. A few months earlier, his wife had died of cancer; she was thirty years younger than him. Home for barely a week from his extensive travels, he sat in his favorite chair, smoking his pipe, near the thousands of records that filled the shelves from floor to ceiling.

In some of the stories in your most recent book, Deshoras, it seems the fantastic is entering into the real world more than ever. Have you yourself felt that, as if the fantastic and the commonplace are becoming one almost?

Yes, in these recent stories I have the feeling that there is less distance between what we call the fantastic and what we call the real. In my older stories the distance was greater because the fantastic was really very fantastic, and sometimes it touched on the supernatural. Well, I am glad to have written those older stories, because I think the fantastic has that quality to always take on metamorphoses, it changes, it can change with time. The notion of the fantastic we had in the epoch of the gothic novels in England, for example, has absolutely nothing to do with our notion today. Now we laugh when we read about the castle of Otranto—the ghosts dressed in white, the skeletons that walk around making noises with their chains. And yet that was the notion of the fantastic at the time. It’s changed a lot. I think my notion of the fantastic, now, more and more approaches what we call reality. Perhaps because for me reality also approaches the fantastic more and more.

Much more of your time in recent years has gone to the support of various liberation struggles in Latin America. Hasn’t that too helped bring the real and the fantastic closer for you? As if it’s made you more serious.

Well, I don’t like the idea of “serious.” Because I don’t think I am serious, in that sense at any rate, where one speaks of a serious man or a serious woman. These last few years all my efforts concerning certain Latin American regimes—Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and now above all Nicaragua—have absorbed me to such a point that even the fantastic in certain stories dealing with this subject is a fantastic that’s very close to reality, in my opinion. So, I feel less free than before. That is, thirty years ago I was writing things that came into my head and I judged them only by esthetic criteria. Now, I continue to judge them by esthetic criteria, because first of all I’m a writer, but I’m a writer who is very tormented, preoccupied by the situation in Latin America. Very often that slips into my writing, in a conscious or in an unconscious way. But in Deshoras, despite the stories where there are very precise references to ideological and political questions, I think my stories haven’t changed. They’re still stories of the fantastic.

The problem for an engagé writer, as they call it now, is to continue being a writer. If what he writes becomes simply literature with a political content, it can be very mediocre. That’s what has happened to a number of writers. So, the problem is one of balance. For me, what I do must always be literature, the highest I can do. To go beyond the possible, even. But, at the same time, very often to try to put in a charge of contemporary reality. And that’s a very difficult balance.

But are you looking to mix the two?

No. Before, the ideas that came to me for stories were of the purely fantastic, while now many ideas are based on the reality of Latin America. In Deshoras, for example, the story about the rats, “Satarsa,” is an episode based on the reality of the fight against the Argentine guerrilleros. The problem is to put it in writing, because one is tempted all the time to let oneself keep going on the political level alone.

What has been the response to such stories? Was there much difference in the response you got from literary people as from political people?

Of course. The bourgeois readers in Latin America who are indifferent to politics or else who even align themselves with the right wing, well, they don’t worry about the problems that worry me—the problems of exploitation, of oppression, and so on. Those people regret that my stories often take a political turn. Other readers, above all the young, who share with me these sentiments, this need to struggle, and who love literature, love these stories. For example, “Apocalypse at Solentiname” is a story that Nicaraguans read and reread with great pleasure. And the Cubans read “Meeting” with lots of pleasure as well.

What has determined your increased political involvement in recent years?

The military in Latin America, they’re the ones who make me work harder. If they get out, if there were a change, then I could rest a little and work on poems and stories that are exclusively literary. But it’s they who give me work to do. The more they are there, the more I must be against them.

You have said various times that for you literature is like a game. In what ways?

For me literature is a form of play. It makes up part of what they call the ludic side of man, homo ludens. But I’ve always added that one must be careful, because there are two forms of play. There’s football, for example, which is a game. And there are games that are very profound and very serious, all while being games. One must consider that when children play, you only have to look at them, they take it very seriously. They’re amusing themselves, but playing is important for them, it’s their main activity. Just as when they’re older, for example, it will be their erotic activity. When they’re little, playing is as serious as love will be ten years later. I remember when I was little, when my parents came to say, “Okay, you’ve played enough, come take a bath now,” I found that completely idiotic, because for me the bath was a silly matter. It had no importance whatsoever, while playing with my friends, that, was something serious. And for me literature is like that, it’s a game but a game where one can put one’s life, one can do everything for that game.

What interested you about the fantastic in the beginning, were you very young?

Oh yes. It began with my childhood. I was very surprised when I was going to grade school, that most of my young classmates had no sense of the fantastic. They were very realistic. They took things as they were . . . that is a plant, that is an armchair. And I was already seeing the world in a way that was very changeable. For me things were not so well defined in that way, there were no labels. My mother, who is a very imaginative woman, helped me a lot. Instead of telling me, “No, no, you should be serious,” she was pleased that I was very imaginative, and when I turned toward the world of the fantastic, she helped me because she gave me books to read. That’s how at the age of nine I read Edgar Allan Poe for the first time. That book I stole to read because my mother didn’t want me to read it, she thought I was too young and she was right. The book scared me and I was ill for three months, because I believed in it--dur comme fer, as the French say. For me the fantastic was perfectly natural. When I read a story of the fantastic, I had no doubts at all. That's the way things were. When I gave them to my friends, the’d say, “But no, I prefer to read cowboy stories.” Cowboys especially at the time. I didn’t understand that. I preferred the world of the supernatural, of the fantastic.

When you translated Poe’s complete works many years later, did you discover new things for yourself from so close a reading?

Many, many things. To begin with, I explored his language, which is highly criticized by the English and the Americans because they find it too baroque, in short they’ve made all sorts of reproaches. Well, since I’m neither English nor American, I see it with another perspective. I know there are aspects which have aged a lot, that are exaggerated, but that hasn’t the least importance next to his genius. To write, in those times, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” that takes an extraordinary genius. To write “Ligeia” or “Berenice,” or “The Black Cat,” any of them, shows a true genius for the fantastic and the supernatural. I should say, in passing, that yesterday I went to a friend’s house on the rue Edgar Allan Poe. There is a plaque where it says, “Edgar Poe, English writer.” He wasn’t English at all! I wanted to point that out because they should change the plaque. We’ll both protest!

In your own writing, besides the fantastic, there is a real warmth and affection for your characters as well.

Certain readers and certain critics have told me that too. That when my characters are children and adolescents, I have a lot of tenderness for them, which is true. I treat them with a lot of love. I think they are very alive in my novels and stories. When I write a story where the character is an adolescent, I am the adolescent while I write it.

Are many of your characters based on people that you’ve known?

I wouldn’t say many, but there are a few. Very often there are characters who are a mixture of two or three people. I have put together female characters from two women I had known. It gave the character in the story or the book a personality that was more complex, more difficult, because she had different ways of being that came from two women.

As with La Maga in Hopscotch?

Well, she is based on one woman, with a lot of psychological characteristics that are completely imaginary. I don’t need to depend on reality to write real things. I invent them, and they become real in the writing. Very often I’m amused because literary critics, especially those who are a bit academic, think that writers don’t have any imagination. They think a writer has always been influenced by this, this and this. They retrace the whole chain of influences. Influences do exist, but these critics forget one thing, that is the pleasure of inventing, pure invention. I know my influences. Edgar Allan Poe is an influence that is very present in certain of my stories. But the rest, it’s I who invent.

Is it when you feel the need to thicken a character that you mix two together? How does that happen?

Things don’t work like that. It’s the characters who direct me. That is, I see a character, he’s there, and I recognize someone I knew or occasionally two who are a bit mixed together, but that stops there. After, the character acts on his own account. He says things. . . I never know what they’re going to say when I’m writing dialogues. Really, it’s among them. Me, I’m typing out what they’re saying. And sometimes I burst out laughing, or I throw out a page because I say, “There you’ve said silly things. Out.” And I put in another page and start again with the dialogue, but there is no fabrication on my part. Really, I don’t fabricate anything.

So it’s not the characters you’ve known that impel you to write?

Not at all, no. Often I have the idea for a story, where there aren’t any characters yet. I’ll have a strange idea: something’s going to happen in a house in the country. I’m very visual when I write, I see everything. So, I see this house in the country and then abruptly I begin to situate the characters. It’s at that point that one of the characters might be someone I knew. But it’s not for sure. In the end, most of my characters are invented. Well, there is myself, there are many autobiographical references in the character of Oliveira in Hopscotch. It’s not me, but there’s a lot of me. Of me here in Paris, in my bohemian days, my first years here. But the readers who read Oliveira as Cortázar in Paris would be mistaken. No, no, I was very different.

Does what you write ever approach too closely the autobiographical?

I don’t like autobiography. I will never write my memoirs. Autobiographies of others interest me, but not my own. Very often, though, when I have ideas for a novel or a story, there are moments of my life, situations, that come very naturally to place themselves there. In the story “Deshoras,” the boy who is in love with his pal’s sister, who is older than him, I lived that. There is a small part of it that’s autobiographical, but from there on, it’s the fantastic or the imaginary which dominates.

You have even written of the need for memoirs by Latin American writers. Why is it you don’t want to write your own?

If I wrote my autobiography, I would have to be truthful and honest. I can’t tell an imaginary autobiography. And so, I would be doing a historian’s job, self-historian, and that bores me. Because I prefer to invent, to imagine.

José Lezama Lima in Paradiso has Cemí saying that “the baroque . . . is what has real interest in Spain and Hispanic America.” Why do you think that is so?

I cannot reply as an expert. The baroque has been very important in Latin America, in the arts and in literature as well. The baroque can offer a great richness; it lets the imagination soar in all its spiraling directions, as in a baroque church with its decorative angels and all that, or in baroque music. But I distrust the baroque a little in Latin America. The baroque writers, very often, let themselves go too easily in writing. They write in five pages what one could very well write in one page, which would be better. I too must have fallen into the baroque because I am Latin American, but I have always had a mistrust of it. I don’t like turgid, voluminous sentences, full of adjectives and descriptions, purring and purring into the reader’s ear. I know it’s very charming, of course, very beautiful, but it’s not me. I’m more on the side of Jorge Luis Borges in that sense. He has always been an enemy of the baroque; he tightened his writing, as with pliers. Well, I write in a very different way than Borges, but the great lesson he gave me is one of economy. He taught me when I began to read him, being very young, that it wasn’t necessary to write these long sentences at the end of which there was some vague thought. That one had to try to say what one wanted to with economy, but with a beautiful economy. It’s the difference perhaps between a plant, which would be the baroque with its multiplications of leaves, it’s very beautiful, and a precious stone, a crystal—that for me is more beautiful still.

The lines are very musical in your writing. Do you usually hear the words as you’re writing them?

Oh yes, I hear them, and I know that in writing—if I’m launched on a story, I write very quickly, because after I can revise—I will never put down a word that is disagreeable to me. There are words I don’t like—not just crude words, those I use when I have to—the sound, the structure of the word displeases me. For example, all the words in juridical and administrative language, they are frequently present in literature. And I hardly ever use those words because I don’t like them.

No, I can’t imagine them in the spirit of your writing.

It’s a question of music, finally. I like music more than literature, I’ve said it many times, I repeat it again, and for me writing corresponds to a rhythm, a heartbeat, a musical pulsation. That’s my problem with translations, because translators of my books sometimes don’t realize that there is a rhythm, they translate the meaning of the words. And I need this swing, this movement that my lines have. Otherwise, the story doesn’t sound right. Above all, certain moments in the stories must be directed musically, because that’s how they give their true meaning. It’s not what they say, but how they say it.

But it’s difficult to be at the same time rhythmically musical and economical like a crystal.

Yes, it’s very difficult, of course. But then I think especially of certain musics that have succeeded in being like that. The best works of Johann Sebastian Bach have the economy with the greatest musical richness. And in a jazz solo, a real jazz solo, a Lester Young solo, for example, at that point there is all the freedom, all the invention, but there is the precise economy that starts and finishes. Not like the mediocre jazz musicians who play for three-quarters of an hour because they have nothing to say, for that I’m very critical of certain forms of contemporary jazz. Because they have nothing more to say, they keep filling up the space. Armstrong, or Ellington, or Charlie Parker only needed two or three minutes to do like Bach, exactly like Johann Sebastian Bach, and Mozart. Writing for me must be like that, a moment from a story must be a beautiful solo. It’s an improvisation, but improvisation involves invention and beauty.

How do you start with your stories? By any particular entry, an image?

With me stories and novels can start anywhere. But on the level of the writing, when I begin to write, the story has been turning around in me a long time, sometimes for weeks. But not in a way that’s clear; it’s a sort of general idea of the story. A house where there’s a red plant in one corner, and then I know that there’s an old man who walks around in this house, and that’s all I know. It happens like that. And then there are the dreams, because during that time my dreams are full of references and allusions to what is going to be in the story. Sometimes the whole story is in a dream. One of my first stories, it’s been very popular, “House Taken Over,” that was a nightmare I had. I got up like that and wrote it. But in general they are fragments of references. That is, my subconscious is in the process of working through a story. The story is being written inside there. So when I say that I begin anywhere, it’s because I don’t know what is the beginning or the end. I start to write and that is the beginning, finally, but I haven’t decided that the story has to start like that. It starts there and it continues. Very often I have no clear idea of the ending, I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s gradually, as the story goes on, that things become clearer and abruptly I see the ending.

So you are discovering the story while you are writing it?

That’s right. I discover it a bit while I am writing. There too is an analogy, I think, with improvisation in jazz. You don’t ask a jazz musician, “But what are you going to play?” He’ll laugh at you. He has simply a theme, a series of chords he has to respect, and then he takes his trumpet or his saxophone and he begins. But he hasn’t the slightest idea . . . it’s not a question of idea. They’re different internal pulsations. Sometimes it comes out well, sometimes it doesn’t. Me, I’m a bit embarrassed to sign my stories. The novels, no, because the novels I worked on a lot; there’s a whole architecture. My stories, it’s as if they were dictated to me a little, by something that is in me, but it’s not me who’s responsible. Well, it does appear they are mine even so, I should accept them!

Are there certain aspects of writing a story that always pose a problem for you?

In general, no, because as I was explaining, the story is already made somewhere inside me. So, it has its dimension, its structure, it’s going to be a very short story or a fairly long story, all that is as if decided in advance. But in recent years I’ve started to sense some problems. I reflect more in front of the page. I write more slowly. And I write in a way that’s more spare. Certain critics have reproached me for that, they’ve told me that little by little I’m losing that suppleness in my stories. I say what I want to, but with a greater economy of means. I don’t know if it’s for better or worse. In any case, it’s my way of writing now.

You were saying that with the novels there is a whole architecture. Does that mean working very differently?

The first thing I wrote in Hopscotch was a chapter that is found in the middle now. It’s the chapter where the characters put out a board to pass from one window to another (chapter 41). Well, I wrote that without knowing why I was writing it. I saw the characters, I saw the situation, it was in Buenos Aires. It was very hot, I remember, and I was next to the window with my typewriter. I saw this situation of a guy who’s trying to make his wife go across, because he’s not going himself, to go get some silly thing, some nails. It was totally ridiculous, in appearance. I wrote all that, which is long, forty pages, and when I finished I said to myself, “All right, but what have I done? Because that’s not a story. What is it?” And then I understood that I was launched on a novel but couldn’t continue. I had to stop there and write the whole section in Paris before. That is, the whole background of Oliveira, because when I wrote the chapter with the board, I was thinking of myself a little at that point. I saw myself as the character, Oliveira was very much me at that point. But to do a novel with that, I had to go backwards before I could continue.

You were in Buenos Aires at that point.

At that point, because after the whole book was written here. This chapter I wrote in Buenos Aires.

And you sensed right away that it was a novel.

I sensed right away that it would be the novel of a city. I wanted to put in the Paris I knew and loved there, in the first part. It would also be a novel about the relations among several characters, but above all the problems, the metaphysical searches of Oliveira, which were mine at the time. Because at that period I was totally immersed in esthetics, philosophy, and metaphysics. I was completely outside of history and politics. In Hopscotch there is no reference to questions of Latin America and its problems. It’s later I discovered that.

You’ve often said that it was the Cuban revolution that awakened you to that.

And I say it again.

Do you revise much when you write?

Very little. That comes from the fact that the thing has already been at work inside me. When I see the rough drafts of certain of my friends, where everything is revised, everything’s changed, moved around, there are arrows all over the place . . . no no no. My manuscripts are very clean.

What are your writing habits? Have certain things changed?

There’s one thing that hasn’t changed, that will never change, that is the total anarchy and the disorder. I have absolutely no method. When I feel like writing a story I let everything drop, I write the story. And sometimes when I write a story, in the month or two that follows I will write two or three stories. In general, it comes in series. Writing one leaves me in a receptive state, and then I catch another story. You see the sort of image I use, but it’s like that, where the story drops inside of me. But after, a year can go by where I write nothing of literature, nothing. I should say too that these last few years I have spent a good deal of my time at the machine writing political articles. The texts I’ve written about Nicaragua, that are distributed through the syndicated press agencies, everything I’ve written about Argentina, they have nothing to do with literature, they’re militant things.

Do you have preferred places for writing?

In fact, no. At the beginning, when I was younger and physically more resistant, here in Paris for example a large part of Hopscotch I wrote in cafes. Because the noise didn’t bother me and, on the contrary, it was a congenial place. I worked a lot there, I read or I wrote. But with age I’ve become more complicated. I write when I’m sure of having some silence. I can’t write if there’s music, that’s absolutely excluded. Music is one thing and writing is another. I need a certain calm; but, this said, a hotel, an airplane sometimes, a friend’s house, or here at home are places where I can write.

About Paris. What gave you the courage to pick up and move off to Paris when you did, more than thirty years ago?

Courage? No, it didn’t take much courage. I simply had to accept the idea that coming to Paris, and cutting the bridges with Argentina at that time, meant being very poor and having problems making a living. But that didn’t worry me. I knew in one way or another I was going to manage. Primarily I came because Paris, French culture on the whole, held a lot of attraction for me. I had read French literature with passion in Argentina. So, I wanted to be here and get to know the streets and the places one finds in the books, in the novels. To go through the streets of Balzac or of Baudelaire. It was a very romantic voyage. I was, I am, very romantic. I have to be rather careful when I write, because very often I could let myself fall into . . . I wouldn’t say bad taste, perhaps not, but a bit in the direction of an exaggerated romanticism. So, there’s a necessary control there, but in my private life I don’t need to control myself. I really am very sentimental, very romantic. I’m a tender person, I have a lot of tenderness to give. What I give now to Nicaragua, it’s tenderness. It is also the political conviction that the Sandinistas are right in what they’re doing and that they’re leading an admirable struggle. But it’s not only the political idea. There’s an enormous tenderness because it’s a people I love. As I love the Cubans, and I love the Argentines. Well, all that makes up part of my character, and in my writing I have had to watch myself. Above all when I was young, I wrote things that were tearjerkers. That was really romanticism, the roman rose. My mother would read them and cry.

Nearly all your writing that people know dates from your arrival in Paris. But you were writing a lot before, weren’t you? A few things had already been published.

I’ve been writing since the age of nine, right up through my whole adolescence and early youth. In my early youth I was already capable of writing stories and novels, which showed me that I was on the right path. But I didn’t want to publish. I was very severe with myself, and I continue to be. I remember that my peers, when they had written some poems or a small novel, searched for a publisher right away. And it was bad, mediocre, because it lacked maturity. I would tell myself, “No, you’re not publishing. You hang onto that.” I kept certain things, and others I threw out. When I did publish for the first time I was over thirty years old; it was a little before my departure for France. That was my first book of stories, Bestiario, which came out in ‘51, the same month I took the boat to come here. Before, I had published a little text called Los Reyes, which is a dialogue. A friend who had a lot of money, who did small editions for himself and his friends, had taken me and done a private edition. And that’s all. No, there’s another thing—a sin of youth—a book of sonnets. I published it myself, but with a pseudonym.

You are the lyricist of a recent album of tangos, Trottoirs de Buenos Aires. What got you started writing tangos?

Well, I am a good Argentine and above all a porteño—that is, a resident of Buenos Aires, because it’s the port. The tango was our music, I grew up in an atmosphere of tangos. We listened to them on the radio, because the radio started when I was little, and right away it was tangos and tangos. There were people in my family, my mother and an aunt, who played tangos on the piano and sang them. Through the radio we began to listen to Carlos Gardel and the great singers of the time. The tango became like a part of my consciousness and it’s the music that sends me back to my youth again and to Buenos Aires. So, I’m quite caught up in the tango. All while being very critical, because I’m not one of those Argentines who believe the tango is the wonder of wonders. I think that the tango on the whole, especially next to jazz, is a very poor music. It is poor but it is beautiful. It’s like those plants that are very simple, that one can’t compare to an orchid or a rosebush, but which have an extraordinary beauty in themselves. In recent years, as I have friends who play tangos here—the Cuarteto Cedrón are great friends, and a fine bandoneon player named Juan José Mosalini—we’ve listened to tangos, talked about tangos. Then one day a poem came to me like that, which perhaps could be set to music, I didn’t really know. And then, looking among unpublished poems, most of my poems are unpublished, I found some short poems which those fellows could set to music, and they did. But we’ve done the opposite experience as well. Cedrón gave me a musical theme, I listened to it, and I wrote the words. So I’ve done it both ways.

In the biographical notes in your books, it says you are also an amateur trumpet player. Did you play with any groups?

No. That’s a bit of a legend that was invented by my very dear friend Paul Blackburn, who died quite young unfortunately. He knew that I played the trumpet a little, for myself at home. So he would always tell me, “But you should meet some musicians to play with.” I’d say, “No,” as the Americans say, “I lack equipment.” I didn’t have the abilities; I was playing for myself. I would put on a Jelly Roll Morton record, or Armstrong, or early Ellington, where the melody is easier to follow, especially the blues which has a given scheme. I would have fun hearing them play and adding my trumpet. I played along with them . . . but it sure wasn’t with them! I never dared approach jazz musicians; now my trumpet is lost somewhere in the other room there. Blackburn put that in one of the blurbs. And because there is a photo of me playing the trumpet, people thought I really could play well. As I didn’t want to publish without being sure, with the trumpet it was the same. And that day never arrived.

Have you worked on any novels since A Manual for Manuel?

Alas no, for reasons that are very clear. It’s due to political work. For me a novel requires a concentration and a quantity of time, at least a year, to work tranquilly and not abandon it. And now, I cannot. A week ago, I didn’t know I would be leaving for Nicaragua in three days. When I return I won’t know what’s going to happen after. But this novel is already written. It’s there, it’s in my dreams. I dream all the time of this novel. I don’t know what happens in the novel, but I have an idea. As in the stories, I know that it will be something fairly long that will have elements of the fantastic, but not so much. It will be, say, in the genre of A Manual for Manuel, where the fantastic elements are mixed in, but it won’t be a political book either. It will be a book of pure literature. I hope that life will give me a sort of desert island, even if the desert island is this room, and a year, I ask for a year. But when these bastards—the Hondurans, the Somocistas, and Reagan—are in the act of destroying Nicaragua, I don’t have my island. I couldn’t begin to write, because I would be obsessed by that all the time. That demands top priority.

And it can be difficult enough as it is with the priorities of life versus literature.

Yes and no. It depends on what kind of priorities. If the priorities are like those I just spoke about, touching on the moral responsibility of an individual, I would agree. But I know many people who are always crying, “Oh, I’d like to write my novel, but I have to sell the house, and then there are the taxes, what am I going to do?” Reasons like, “I work in the office all day, how do you expect me to write?” Me, I worked all day at UNESCO and then I came home and wrote Hopscotch. When one wants to write, one writes. If one is condemned to write, one writes.

Do you work anymore as a translator or interpreter?

No, that’s over. I lead a very simple life. I don’t need much money for the things I like: records, books, tobacco. So now I can live from my royalties. They’ve translated me into so many languages that I receive enough money to live on. I have to be a little careful; I can’t go out and buy myself a yacht, but since I have absolutely no intention of buying a yacht . . .

Have you enjoyed your fame and success?

Ah, listen, I’ll say something I shouldn’t say because no one will believe it, but success is not a pleasure for me. I’m glad to be able to live from what I write, so I have to put up with the popular and critical side of success. But I was happier as a man when I was unknown, much happier. Now I can’t go to Latin America or to Spain without being recognized every ten yards, and the autographs, the embraces . . . It’s very moving, because they’re readers who are frequently quite young. I’m happy they like what I do, but it’s terribly distressing for me on the level of privacy. I can’t go to a beach in Europe; in five minutes there’s a photographer. I have a physical appearance that I can’t disguise; if I were small I could shave and put on sunglasses, but with my height, my long arms and all that, they recognize me from afar. On the other hand, there are very beautiful things: I was in Barcelona a month ago, walking around the gothic quarter one evening, and there was an American girl, very pretty, playing the guitar very well and singing. She was seated on the ground earning her living. She sang a bit like Joan Baez, a very pure, clear voice. There was a group of young people from Barcelona listening. I stopped to listen to her, but I stayed in the shadows. At a certain point, one of these young men who was about twenty, very young, very handsome, approached me. He had a cake in his hand. He said, “Julio, take a piece.” So I took a piece and ate it, and I told him, “Thanks a lot for coming up and giving that to me.” And he said to me, “But, listen, I give you so little next to what you’ve given me.” I said, “Don’t say that, don’t say that,” and we embraced and he went away. Well, things like that, that’s the best recompense for my work as a writer. That a boy or a girl come up to speak to you and to offer you a piece of cake, it’s wonderful. It’s worth the trouble of having written.