Out Loud and In French, Mostly

Jacques Prévert: 100 ans

Paris: Radio France/INA, 2000

Voix de poètes III

Paris: Radio France/INA, 1999

Luna Park 0,10

Brussels: Sub Rosa, 1999

published in American Book Review (Normal, IL) 22:1 (Nov.-Dec. 2000)

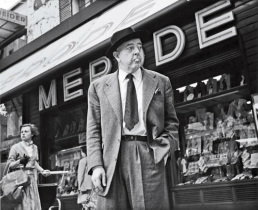

Jacques Prévert was a unique figure among writers. Besides his many books of poetry and children’s stories, he was France’s first important screenwriter. Through the 1930s and 1940s, above all with director Marcel Carné, he helped create the poetic realism of films such as Quai des brumes, Le jour se lève, and Les enfants du paradis. He was an early friend of the surrealists, and his work always retained a fanciful spirit mixed with a perpetual critique of bourgeois society. In the 1930s, as another outlet for the populist aesthetics seen in his language and his themes, he formed the Groupe Octobre, which included Marcel Duhamel and Roger Blin, and for which he wrote most of the plays. A sort of agit-prop theater troupe with a high dose of humor, they performed at union meetings, workers’ strikes, and political rallies. And by way of the films, whose scores were often composed by Joseph Kosma, Prévert became a noted lyricist as well; their most famous song, “Les feuilles mortes (Autumn Leaves),” from Carné’s Les portes de la nuit (1946), has been performed in hundreds of versions worldwide. No wonder his best-known book of poetry, dating from that same year, was called Paroles (translated by Ferlinghetti ten years later): the specific term for spoken words, it also means song lyrics.

Given the oral quality of his work, it is fitting that the most sumptuous celebration this year marking the centenary of his birth be presented on disc. Jacques Prévert: 100 ans, a four-CD set in French, produced by Radio France and the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA), is structured thematically: Childhood, Love, Music, Freedom. Each program mixes interviews with various collaborators, texts read by Prévert and others, and many songs, drawn mostly from archival recordings that span four decades. Indeed, with its intricate weave of voices and materials, the project deserves to have a much more detailed and extensive booklet, replete with photos; what is provided instead serves as barely a list.

On the other hand, listening to the discs, we plunge directly into the Prévert experience, a poetic distillation of the hopes and dreams and also regrets of ordinary Parisians from the time of the Popular Front through the postwar decades. Some of the highlights: Pierre Brasseur’s animated reading of “Le dromadaire mécontent,” Marlene Dietrich singing “Déjeuner du matin” (its meticulous account of a man’s morning ritual, his coffee and cigarette, “without speaking to me, without looking at me”), Arletty and Juliette Gréco each recalling their work with him, “La chanson des petits métiers” sung by Charles Trenet (from a 1943 film by Prévert’s younger brother Pierre), “Pater Noster” read by Prévert (“Our Father who art in heaven, stay there, and we shall stay on the earth which is so pretty sometimes”), and the colorful accounts of his anticlericalism. Never mind the dissertations, this is the place to start and to return to when reading Prévert.

For much of the past century, the French, mostly by way of such state institutions, have been busy recording and preserving the voices of numerous writers reading their own texts. Radio France with INA has released on CD a selection from that ongoing enterprise, with the latest, Voix de poètes III, covering the period 1950-1980. The earliest in the series ranged from Apollinaire to Saint John Perse, while the second included Cendrars, Colette, Tzara, Céline. The new volume of readings---23 poets in a one-hour program---opens out onto the modern world of French culture by including many poets from beyond Europe (Andrée Chédid, Césaire, Depestre, Senghor), while placing them among their adventurous peers (Char, Genet, Sarraute, Le Clézio). What is surprising to this foreigner’s ear must be the triumph of the French educational system: no matter their diverse origins, no matter the accents or tonal coloring of the voices, all of these writers enunciate with a more or less classical diction; it is hard to imagine a comparable range of writers in English being as comprehensible.

As to what their voices sound like, expectations are quickly derailed, particularly on hearing writers of prose. Roger Caillois, reading from L’écriture des pierres, treats his studious text like a poem of the marvelous. Or Jean Genet, with his pinched voice reading from Le journal du voleur, seems almost sweet as he claims his place among the damned. The sequence in which the writers are presented is especially effective, crisscrossing the French-speaking world at each turn. After Genet, René Depestre advances his own critique of the Christian West, followed by Raymond Queneau’s playful “Explication des métaphores”; likewise, the globe-trotting Jean-Marie Le Clézio is followed by the prayerful Tchicaya U’Tamsi, from the Congo, and then the fiery Gaston Miron, from Quebec.

Based in Brussels, the provocative Sub Rosa label has produced a number of literary CDs in English and French, devoted to Marcel Duchamp, Paul Bowles, William S. Burroughs, Brion Gysin, Ira Cohen, as well as Antonin Artaud’s banned 1947 program for French radio, Pour en finir avec le jugement de dieu. A new anthology edited by Marc Dachy, named after his journal from the 1970-80s, Luna Park 0,10 presents a historical panorama of the international avant garde that could nicely complement the Rothenberg-Joris book anthologies Poems for the Millennium. Half of the recordings used to be available elsewhere, but gathered together in one place they help make the collection a real treasure, starting with Apollinaire and “Le Pont Mirabeau.” Inevitably, the listener comes up against the language barrier, with Mayakovsky for instance, but a piece like Kurt Schwitters’ “Ursonate” renders that obstacle irrelevant. Consider the wealth of other writers here: James Joyce (“Anna Livia Plurabelle”), Gertrude Stein (“If I Told Him,” “A Valentine to Sherwood Anderson”), Artaud (“Aliénation et magie noire”), Tzara, Duchamp (“The Creative Act”), e. e. cummings, Gysin (three Permutation Poems), Julian Beck, Pierre Guyotat, ending with the Brazilian concrete poet Augusto de Campos. More details on the sources of these recordings would have been instructive, but, regardless, the anthology offers a marvelous portal to many of the experimental literary paths of the past century that are still being explored to this day.