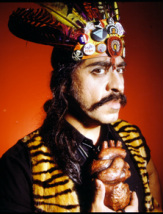

_Guillermo Gómez-Peña

published in Review: Latin American Literature and Arts (New York) 45 (July 1991)

Describing himself as "a border linguist, a performance activist, a vernacular anthropologist," interdisciplinary artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña works in the interstices between languages. He employs English, Spanish, Spanglish, Ingleñol, and other hybrids to create an experience of "cultural vertigo," seeing the border with Mexico as the Berlin Wall of the Americas.

Born in Mexico City in 1955, Gómez-Peña studied literature and linguistics at the UNAM, the national university. Already staging performance events with collaborators, he moved to the US in 1978 to continue his studies at Cal Arts, near Los Angeles. In 1980, he cofounded Poyesis Genética, a cross-cultural performance troupe working to "hybridize" their own esthetic traditions. After moving to the San Diego-Tijuana border region, he became a founding member in 1985 of the Border Arts Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo, a group of art activists responding to the need "to generate a binational dialogue between Mexicans and Chicanos." He is also co-editor of the experimental arts magazine The Broken Line/La Línea Quebrada; an associate of Post-Arte, the network of Latin American conceptual artists and visual poets; a writer for journals on both sides of the border; a contributor to public radio and a collaborator in two films. The film version of his solo performance piece Border Brujo, shot by Isaac Artenstein, is available on video, and several collections of his writings have been published as well. In 1991, a month before this interview, he received a MacArthur Foundation award, just as he was midway through work on his new performance trilogy, 1992.

You've performed for many different audiences, inside and outside the art world. How do you approach these various audiences? What have been their responses?

I'm trying to experiment with bilingualism and biculturalism in a different way. Traditionally, in Chicano literature for example, the roles that Spanish and English had were very specific. Often Spanish was for the private world and English for the public world, or Spanish for the past and English for the present, Spanish for family and English for politics. I'm trying to go beyond that, to develop more dynamic mechanisms of the use of bilingualism and biculturalism. Often by developing multiple discourses on the stage in which different sectors of the audience can have access in different degrees to these levels. There is a level of total complicity for the fully bilingual and bicultural, there is a level of otherness and confrontation for the monolingual English-speaking audience member, and there is a level of partial confrontation for the monolingual Spanish-speaking member. Also, in terms of being able to decodify the images, I like to explore this territory of cultural misunderstanding---to me, that is what border culture is, above all, a territory of cultural misunderstanding---and I try to perform cultural mistakes. I try to crack open symbols and metaphors, right in front of the audience, because that is what happens to symbols when they cross the border. I want to mislead my audience, to disorient them culturally, to pull the rug out from under them constantly. So, at any given moment in the performance, different sectors of the audience are experiencing very different things. Some people might feel segregated at one point, others feel total empathy; some people might feel disoriented, others might feel validated. And these proportions change at different times. The response of my audiences also changes depending on the context where I perform. It is not the same to perform for Chicanos as for Anglo-Americans who resist acculturation. What I try to do in my work is to force people to take positions in relation to certain issues, such as: bilingual education, human rights, US-Mexico relations, matters of self and other, center and periphery, the relationship between Anglo-European culture and the Latin American other.

Does performing outside America add another dynamic?

I've been to Europe, Canada, the Soviet Union, and Mexico. Certainly in Mexico there is more context. In Canada, Europe, and the Soviet Union, it's harder to build a bridge, but I think that most of the times I am able to do it. Most of these countries have a third world within themselves, so I try to make that link between the Latin American experience within the US and, let's say, the Pakistani experience in England, or the North African in France. Last year I went to the Soviet Far East, to Vladivostok, and I performed my work there. It was much harder certainly, because their codes for Western performance art were non-existent, but I managed to be able to put the work in context by explaining that it took place right in the space between the so-called third world and the first world---in their case between dominant Soviet society and their multiracial communities of the Far East, such as the Mongolians, the Siberians, the Chinese, the Koreans. I think they got the point.

How does the different language spoken by the audience affect the reception of the performance?

The most radical experience of linguistic otherness I ever had was in the Soviet Union. In northern Europe, most people speak English. I have also performed in Quebec, and it was very easy to make that link between the Chicano and the Quebecois. Many Quebecois consider themselves Latinos, they have undergone similar cultural processes. In the Soviet Union, I had to perform with interpreters. I had two translators on the stage, and it was kind of ridiculous but at the same time very interesting. I would stop my monologue and freeze, while a translator would come on the stage and try to translate my Spanglish into Russian! Which means, a performance that would have taken a half-hour in performance time took practically two hours.

In Mexico do your different levels of discourse get through?

Sadly, I haven't performed as much as I want in Mexico, because of the lack of context for experimental performance art. But my films and my experimental radio work are known, and my writings. In the northern Mexico border area, I have performed for years. Generally, contemporary Mexicans, both from the center and the border cities, are very much in tune with border issues. Certainly, the North American presence is one of the major subject matters of contemporary Mexican culture, and how to deal with it is something that the Chicano border artists are in many ways anticipating for central Mexico.

Do you have much contact with the rest of Latin America?

Yes. There is a Latin American experimental arts milieu, whose network might not be as robust as in painting, but we have managed through mail art, informal video showings, sporadic symposia, and some magazines, to keep a continental dialogue going between Latin American artists who practice performance, video, conceptual art, and audio art.

The past couple of years you've been working on the performance trilogy 1992. How has it developed so far?

The first part was commissioned by the Los Angeles Festival, and presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles last year. It involved both live performance and a binational radio show that we produced. The second part premiered recently at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as part of the Next Wave Festival. The piece utilizes my kind of experimental performance languages, which is a syncretic blend of many traditions and art forms. I try to articulate some of the complexities of the debates around Columbus, and their relationship to contemporary issues in the US. Like my previous work, the piece goes back and forth from the personal to the historical, from the poetical to the political, from social reality to literary fiction. And, of course, from Spanish to English.

How do the parts fit together? How do they differ?

This trilogy is about el redescubrimiento y la reconquista cultural of the US by Latinos. In the first part, I was very interested in exploring the ritual possibilities of the spoken word, the performed word. As in Border Brujo, it was a monologue sitting at a table. In it I experimented with dialectal forms of Spanish, Spanglish, English, tongues, native languages, and tried to construct a multilingual epic. The second part of the trilogy is much more elaborate. I undergo a number of changes of costumes and characters. I utilize a map as set design, and depending on the place on the map where I am, my language changes. I undergo a linguistic journey across my personal topography. I also use a number of props, mostly pop cultural artifacts and tourist icons which I use as "sacred objects." And I'm collaborating with a number of artists in different territories: Mexican filmmaker Isaac Artenstein did a video for the piece; writer and artist Coco Fusco conceived a pre-performance event, she was Queen Isabela signing deeds to the New World as the audience members entered the lobby; Puerto Rican visual artist Pepón Osorio designed costumes; Mexican journalist Marco Vinicio González designed the sound; Chicano artist Roberto Sifuentes was technical director. I'm very interested in using art as cross-cultural diplomacy, and so I'm trying to put together this bicoastal team of artists. In this particular case, I'm working with Mexican and Chicano artists from the West Coast as well as Caribbean Latinos from the East Coast. So there is this other dimension of diplomacy which is unseen to the audience, but to me it's extremely important.

How do the themes or subjects differ in the parts of 1992?

Well, there is really not a plot, more like a series of vignettes poetically linked together. Most of the characters I work with are hybrids, half traditional and half contemporary, half Mexican and half Chicano. They include El Aztec High-Tech, El Caballero Tigre (The Tiger Knight), El Mariachi Liberachi, and El Warrior for Gringostroika. They are mythical characters. Each articulates within himself a series of cultural contradictions which are at the core of the US-Latino experience. There are a number of subject matters interwoven throughout the entire trilogy: diaspora, deterritorialization, the border wound, the Mexican-American migrant experience, and how they filter through language and memory. In a sense, I am rediscovering America through my own immigrant experience. I turn the continent upside down, so to speak, to become the speaking subject, the Latino vernacular anthropologist who looks at the US with new eyes.

Have you found a certain advantage in the difficult position of being neither entirely a Mexican artist nor a Chicano?

I am constantly perplexed by the intensity and passion with which certain Mexican and Chicano sectors claim and reject me. My work is very paradigmatic in this sense. I am equidistant from Mexico and the Chicano experience. I often see myself as a chicalango, a chilango/Chicano [chilango: a person from Mexico City]. I see my identity as hyphenated; I am this and that at the same time.

In the second part of your trilogy you are more physically active than in the previous pieces. Was there a specific desire to put your body more into the new work?

As performance artists we have to constantly change our strategies of communication. From 1985 to 1990 there was a very strong performance art monologue movement---Eric Bogosian, Spalding Gray, Karen Finley, Tim Miller---and I was part of it. Our idea was to react against the technological complexities and overstaging of previous performance experiments, and to rescue the spoken word, the live word. But times are changing. I am now looking for new esthetic strategies. Language is still the main character of my work, but I am experimenting with more dynamic ways of presenting it.

Was Border Brujo your first major solo piece?

No. It was the one that drew more attention, because I took it on the road for practically two years. It got me an international prize in Montreal, and a Bessie award in the US. From '87 to '89 it gave me this visibility and the opportunity to become a migrant performance artist.

Did the piece develop a lot through that time?

Yeah. That's how I work, unlike traditional theatre.

You're constantly reworking it.

Constantly. I begin presenting my work a few weeks after I have conceived it. I test my work first with friends and colleagues, and eventually I take it on the road. I present it informally, as a work in progress, in universities, galleries, and alternative spaces, and on the road it becomes slowly rounded, it finds its true shape.

How did Border Brujo develop?

First I work on the text as a poem. It is first a literary experience, and then slowly it achieves a kind of three-dimensionality. I play with the plasticity of the words, and slowly I begin establishing links between spoken language and gesture, action and objects---small sculptures, props, ritual artifacts, and costumes. The performance unfolds throughout the months. In other words, the first times I present my material, it's mostly this border madman screaming from a table, with a megaphone, a couple of mikes, a bunch of candles, and that's about it. Throughout the months my delivery becomes more complex and theatrical. Eventually after a year more or less, I think that I finally have a piece. It takes a while, it's a long process and I don't like to speed it up.

Did you retire Border Brujo?

I decided to bury him. Like I do with most of my characters, once my performance is over. I literally take the costumes, the masks, and the script, and I bury them where I feel it's more meaningful to bury them. In the case of the Brujo, on the US-Mexico border. I don't know where I will bury my Warrior for Gringostroika, perhaps in Washington.

Do you think that American audiences have become more aware of the Latin American experience in the past decade?

Yes and no. When Americans speak about Mexican art, they think of folk art, muralism, magical realism, at best of Octavio Paz or Juan Rulfo. But the social and anthropological realities of contemporary Mexico are different. Post-earthquake Mexico City is a postmodern architecture in ruins. And the voices that are emerging out of these ruins are the voices of charróck (charro and rock), of cholo punk, of the young Mexican cartoonists, for example. These voices, like the everyday experience of the city, are strident, confrontational, and totally hybrid.

One of your targets over the years has been the art world. It seems recently that with major commissions and the MacArthur Award, you've been accepted into the club. Does that threaten to take the edge off your work?

I am hoping this recognition will give me the possibility to speak more from the center. Artists as cultural and social critics are extremely necessary voices, especially in a country that doesn't pay attention to the mind of the artist but just to style and hype. So, if this recent recognition can help me develop my negotiating powers, and amplify the scope of my public voice, I think it's important that I shouldn't shy away from it. The main challenge in a society like the US is how to differentiate between having a public voice and fame, between the culture of dialogue and the culture of hype. I think the Latin American model is a much more enlightened one, in which intellectuals and artists are not just celebrities but their voices are part of the national debates.

How do you see the issues today that you first confronted as a member of the Border Arts Workshop?

One of the hardest things for Latinos in the US is to maintain a clear sense of national self. We're completely disenfranchised, completely fractured---ideologically, socially, culturally. Not just between Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Central Americans, but also within our immediate communities. More than ever we need cross-cultural diplomats who can walk the border between Nuyorico and Aztlán, between Cuba York and San Francisco, between East LA and Spanish Harlem, between San Antonio and Miami. We need these citizen diplomats, to begin creating this pan-Latin American web within the US. Artists can perform these functions better than politicians.

One of the differences between Latino performance art and the New York avant garde has to do with the fact that we are very interested in consensus and in paradigmatic experience. As opposed to just rarefied experimentation taking place outside history and society. Our relationship with popular culture is crucial, because popular culture can give us a larger context for many people to understand. Also, we're always looking for the connection with matters of life and death for our communities. We are constantly recycling the opinion of our audiences into the piece in order to create a work that is meaningful to more than a handful of eccentric artists, so that we can be part of a larger intellectual and political community. I mean, we are attempting to define the great paradigms of our time: crisis, rupture, dislocation, syncretism, migration, and transculture.

You've noted the importance of Mexico City as a gateway for North and South, also of Tijuana-San Diego as a new axis of communication. Do you see larger stretches of such routes?

I am very interested in designing alternative cartographies. I see myself as a kind of utopian mapmaker. In this sense, I am trying to redefine cartography in terms that are more culturally pertinent to me and my people. When I was at the US-Mexico border I talked about that axis, between Mexico City via Tijuana, San Diego, Los Angeles, that went all the way up to San Francisco. It was both an historical axis---las misiones---and a migratory pattern, and more recently a very important axis for intellectuals and artists to exchange ideas.

The work I was doing was trying to create a dialogue and open up that axis more. Now, I am very interested in what I call my personal Bermuda Triangle, which connects Manhattan and Mexico City with Tijuana---three urban centers, three aberrations, which are undergoing very similar demographic and cultural processes. But these alternative cartographies are making more sense to me.

published in Review: Latin American Literature and Arts (New York) 45 (July 1991)

Describing himself as "a border linguist, a performance activist, a vernacular anthropologist," interdisciplinary artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña works in the interstices between languages. He employs English, Spanish, Spanglish, Ingleñol, and other hybrids to create an experience of "cultural vertigo," seeing the border with Mexico as the Berlin Wall of the Americas.

Born in Mexico City in 1955, Gómez-Peña studied literature and linguistics at the UNAM, the national university. Already staging performance events with collaborators, he moved to the US in 1978 to continue his studies at Cal Arts, near Los Angeles. In 1980, he cofounded Poyesis Genética, a cross-cultural performance troupe working to "hybridize" their own esthetic traditions. After moving to the San Diego-Tijuana border region, he became a founding member in 1985 of the Border Arts Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo, a group of art activists responding to the need "to generate a binational dialogue between Mexicans and Chicanos." He is also co-editor of the experimental arts magazine The Broken Line/La Línea Quebrada; an associate of Post-Arte, the network of Latin American conceptual artists and visual poets; a writer for journals on both sides of the border; a contributor to public radio and a collaborator in two films. The film version of his solo performance piece Border Brujo, shot by Isaac Artenstein, is available on video, and several collections of his writings have been published as well. In 1991, a month before this interview, he received a MacArthur Foundation award, just as he was midway through work on his new performance trilogy, 1992.

You've performed for many different audiences, inside and outside the art world. How do you approach these various audiences? What have been their responses?

I'm trying to experiment with bilingualism and biculturalism in a different way. Traditionally, in Chicano literature for example, the roles that Spanish and English had were very specific. Often Spanish was for the private world and English for the public world, or Spanish for the past and English for the present, Spanish for family and English for politics. I'm trying to go beyond that, to develop more dynamic mechanisms of the use of bilingualism and biculturalism. Often by developing multiple discourses on the stage in which different sectors of the audience can have access in different degrees to these levels. There is a level of total complicity for the fully bilingual and bicultural, there is a level of otherness and confrontation for the monolingual English-speaking audience member, and there is a level of partial confrontation for the monolingual Spanish-speaking member. Also, in terms of being able to decodify the images, I like to explore this territory of cultural misunderstanding---to me, that is what border culture is, above all, a territory of cultural misunderstanding---and I try to perform cultural mistakes. I try to crack open symbols and metaphors, right in front of the audience, because that is what happens to symbols when they cross the border. I want to mislead my audience, to disorient them culturally, to pull the rug out from under them constantly. So, at any given moment in the performance, different sectors of the audience are experiencing very different things. Some people might feel segregated at one point, others feel total empathy; some people might feel disoriented, others might feel validated. And these proportions change at different times. The response of my audiences also changes depending on the context where I perform. It is not the same to perform for Chicanos as for Anglo-Americans who resist acculturation. What I try to do in my work is to force people to take positions in relation to certain issues, such as: bilingual education, human rights, US-Mexico relations, matters of self and other, center and periphery, the relationship between Anglo-European culture and the Latin American other.

Does performing outside America add another dynamic?

I've been to Europe, Canada, the Soviet Union, and Mexico. Certainly in Mexico there is more context. In Canada, Europe, and the Soviet Union, it's harder to build a bridge, but I think that most of the times I am able to do it. Most of these countries have a third world within themselves, so I try to make that link between the Latin American experience within the US and, let's say, the Pakistani experience in England, or the North African in France. Last year I went to the Soviet Far East, to Vladivostok, and I performed my work there. It was much harder certainly, because their codes for Western performance art were non-existent, but I managed to be able to put the work in context by explaining that it took place right in the space between the so-called third world and the first world---in their case between dominant Soviet society and their multiracial communities of the Far East, such as the Mongolians, the Siberians, the Chinese, the Koreans. I think they got the point.

How does the different language spoken by the audience affect the reception of the performance?

The most radical experience of linguistic otherness I ever had was in the Soviet Union. In northern Europe, most people speak English. I have also performed in Quebec, and it was very easy to make that link between the Chicano and the Quebecois. Many Quebecois consider themselves Latinos, they have undergone similar cultural processes. In the Soviet Union, I had to perform with interpreters. I had two translators on the stage, and it was kind of ridiculous but at the same time very interesting. I would stop my monologue and freeze, while a translator would come on the stage and try to translate my Spanglish into Russian! Which means, a performance that would have taken a half-hour in performance time took practically two hours.

In Mexico do your different levels of discourse get through?

Sadly, I haven't performed as much as I want in Mexico, because of the lack of context for experimental performance art. But my films and my experimental radio work are known, and my writings. In the northern Mexico border area, I have performed for years. Generally, contemporary Mexicans, both from the center and the border cities, are very much in tune with border issues. Certainly, the North American presence is one of the major subject matters of contemporary Mexican culture, and how to deal with it is something that the Chicano border artists are in many ways anticipating for central Mexico.

Do you have much contact with the rest of Latin America?

Yes. There is a Latin American experimental arts milieu, whose network might not be as robust as in painting, but we have managed through mail art, informal video showings, sporadic symposia, and some magazines, to keep a continental dialogue going between Latin American artists who practice performance, video, conceptual art, and audio art.

The past couple of years you've been working on the performance trilogy 1992. How has it developed so far?

The first part was commissioned by the Los Angeles Festival, and presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles last year. It involved both live performance and a binational radio show that we produced. The second part premiered recently at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as part of the Next Wave Festival. The piece utilizes my kind of experimental performance languages, which is a syncretic blend of many traditions and art forms. I try to articulate some of the complexities of the debates around Columbus, and their relationship to contemporary issues in the US. Like my previous work, the piece goes back and forth from the personal to the historical, from the poetical to the political, from social reality to literary fiction. And, of course, from Spanish to English.

How do the parts fit together? How do they differ?

This trilogy is about el redescubrimiento y la reconquista cultural of the US by Latinos. In the first part, I was very interested in exploring the ritual possibilities of the spoken word, the performed word. As in Border Brujo, it was a monologue sitting at a table. In it I experimented with dialectal forms of Spanish, Spanglish, English, tongues, native languages, and tried to construct a multilingual epic. The second part of the trilogy is much more elaborate. I undergo a number of changes of costumes and characters. I utilize a map as set design, and depending on the place on the map where I am, my language changes. I undergo a linguistic journey across my personal topography. I also use a number of props, mostly pop cultural artifacts and tourist icons which I use as "sacred objects." And I'm collaborating with a number of artists in different territories: Mexican filmmaker Isaac Artenstein did a video for the piece; writer and artist Coco Fusco conceived a pre-performance event, she was Queen Isabela signing deeds to the New World as the audience members entered the lobby; Puerto Rican visual artist Pepón Osorio designed costumes; Mexican journalist Marco Vinicio González designed the sound; Chicano artist Roberto Sifuentes was technical director. I'm very interested in using art as cross-cultural diplomacy, and so I'm trying to put together this bicoastal team of artists. In this particular case, I'm working with Mexican and Chicano artists from the West Coast as well as Caribbean Latinos from the East Coast. So there is this other dimension of diplomacy which is unseen to the audience, but to me it's extremely important.

How do the themes or subjects differ in the parts of 1992?

Well, there is really not a plot, more like a series of vignettes poetically linked together. Most of the characters I work with are hybrids, half traditional and half contemporary, half Mexican and half Chicano. They include El Aztec High-Tech, El Caballero Tigre (The Tiger Knight), El Mariachi Liberachi, and El Warrior for Gringostroika. They are mythical characters. Each articulates within himself a series of cultural contradictions which are at the core of the US-Latino experience. There are a number of subject matters interwoven throughout the entire trilogy: diaspora, deterritorialization, the border wound, the Mexican-American migrant experience, and how they filter through language and memory. In a sense, I am rediscovering America through my own immigrant experience. I turn the continent upside down, so to speak, to become the speaking subject, the Latino vernacular anthropologist who looks at the US with new eyes.

Have you found a certain advantage in the difficult position of being neither entirely a Mexican artist nor a Chicano?

I am constantly perplexed by the intensity and passion with which certain Mexican and Chicano sectors claim and reject me. My work is very paradigmatic in this sense. I am equidistant from Mexico and the Chicano experience. I often see myself as a chicalango, a chilango/Chicano [chilango: a person from Mexico City]. I see my identity as hyphenated; I am this and that at the same time.

In the second part of your trilogy you are more physically active than in the previous pieces. Was there a specific desire to put your body more into the new work?

As performance artists we have to constantly change our strategies of communication. From 1985 to 1990 there was a very strong performance art monologue movement---Eric Bogosian, Spalding Gray, Karen Finley, Tim Miller---and I was part of it. Our idea was to react against the technological complexities and overstaging of previous performance experiments, and to rescue the spoken word, the live word. But times are changing. I am now looking for new esthetic strategies. Language is still the main character of my work, but I am experimenting with more dynamic ways of presenting it.

Was Border Brujo your first major solo piece?

No. It was the one that drew more attention, because I took it on the road for practically two years. It got me an international prize in Montreal, and a Bessie award in the US. From '87 to '89 it gave me this visibility and the opportunity to become a migrant performance artist.

Did the piece develop a lot through that time?

Yeah. That's how I work, unlike traditional theatre.

You're constantly reworking it.

Constantly. I begin presenting my work a few weeks after I have conceived it. I test my work first with friends and colleagues, and eventually I take it on the road. I present it informally, as a work in progress, in universities, galleries, and alternative spaces, and on the road it becomes slowly rounded, it finds its true shape.

How did Border Brujo develop?

First I work on the text as a poem. It is first a literary experience, and then slowly it achieves a kind of three-dimensionality. I play with the plasticity of the words, and slowly I begin establishing links between spoken language and gesture, action and objects---small sculptures, props, ritual artifacts, and costumes. The performance unfolds throughout the months. In other words, the first times I present my material, it's mostly this border madman screaming from a table, with a megaphone, a couple of mikes, a bunch of candles, and that's about it. Throughout the months my delivery becomes more complex and theatrical. Eventually after a year more or less, I think that I finally have a piece. It takes a while, it's a long process and I don't like to speed it up.

Did you retire Border Brujo?

I decided to bury him. Like I do with most of my characters, once my performance is over. I literally take the costumes, the masks, and the script, and I bury them where I feel it's more meaningful to bury them. In the case of the Brujo, on the US-Mexico border. I don't know where I will bury my Warrior for Gringostroika, perhaps in Washington.

Do you think that American audiences have become more aware of the Latin American experience in the past decade?

Yes and no. When Americans speak about Mexican art, they think of folk art, muralism, magical realism, at best of Octavio Paz or Juan Rulfo. But the social and anthropological realities of contemporary Mexico are different. Post-earthquake Mexico City is a postmodern architecture in ruins. And the voices that are emerging out of these ruins are the voices of charróck (charro and rock), of cholo punk, of the young Mexican cartoonists, for example. These voices, like the everyday experience of the city, are strident, confrontational, and totally hybrid.

One of your targets over the years has been the art world. It seems recently that with major commissions and the MacArthur Award, you've been accepted into the club. Does that threaten to take the edge off your work?

I am hoping this recognition will give me the possibility to speak more from the center. Artists as cultural and social critics are extremely necessary voices, especially in a country that doesn't pay attention to the mind of the artist but just to style and hype. So, if this recent recognition can help me develop my negotiating powers, and amplify the scope of my public voice, I think it's important that I shouldn't shy away from it. The main challenge in a society like the US is how to differentiate between having a public voice and fame, between the culture of dialogue and the culture of hype. I think the Latin American model is a much more enlightened one, in which intellectuals and artists are not just celebrities but their voices are part of the national debates.

How do you see the issues today that you first confronted as a member of the Border Arts Workshop?

One of the hardest things for Latinos in the US is to maintain a clear sense of national self. We're completely disenfranchised, completely fractured---ideologically, socially, culturally. Not just between Cubans, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and Central Americans, but also within our immediate communities. More than ever we need cross-cultural diplomats who can walk the border between Nuyorico and Aztlán, between Cuba York and San Francisco, between East LA and Spanish Harlem, between San Antonio and Miami. We need these citizen diplomats, to begin creating this pan-Latin American web within the US. Artists can perform these functions better than politicians.

One of the differences between Latino performance art and the New York avant garde has to do with the fact that we are very interested in consensus and in paradigmatic experience. As opposed to just rarefied experimentation taking place outside history and society. Our relationship with popular culture is crucial, because popular culture can give us a larger context for many people to understand. Also, we're always looking for the connection with matters of life and death for our communities. We are constantly recycling the opinion of our audiences into the piece in order to create a work that is meaningful to more than a handful of eccentric artists, so that we can be part of a larger intellectual and political community. I mean, we are attempting to define the great paradigms of our time: crisis, rupture, dislocation, syncretism, migration, and transculture.

You've noted the importance of Mexico City as a gateway for North and South, also of Tijuana-San Diego as a new axis of communication. Do you see larger stretches of such routes?

I am very interested in designing alternative cartographies. I see myself as a kind of utopian mapmaker. In this sense, I am trying to redefine cartography in terms that are more culturally pertinent to me and my people. When I was at the US-Mexico border I talked about that axis, between Mexico City via Tijuana, San Diego, Los Angeles, that went all the way up to San Francisco. It was both an historical axis---las misiones---and a migratory pattern, and more recently a very important axis for intellectuals and artists to exchange ideas.

The work I was doing was trying to create a dialogue and open up that axis more. Now, I am very interested in what I call my personal Bermuda Triangle, which connects Manhattan and Mexico City with Tijuana---three urban centers, three aberrations, which are undergoing very similar demographic and cultural processes. But these alternative cartographies are making more sense to me.