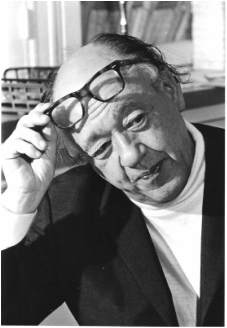

Eugène Ionesco

published in City Lights Review (San Francisco) 3 (Nov. 1989), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (1991), now out of print

It was with his first play, La cantatrice chauve (The Bald Soprano), in Paris 1950, that Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994) became famous. One of the leading dramatists in the “theater of the absurd,” as critics billed it, Ionesco followed with The Lesson, The Chairs, Rhinoceros, Exit the King, as well as more plays, short stories, theater criticism, journals, polemics, and a novel. His last play, Journeys among the Dead, was written in 1980.

Since then, he has also returned to painting, which he first took up over ten years earlier. “Painting retaught me the taste for writing by hand,” he says. In 1988 he published La quête intermittente, which he describes as “autobiographical reflections, flashes, thoughts, meditations, different things, and the quest is intermittent because it is the quest for the absolute.”

Born in Romania in 1909 of a French mother, Ionesco spent his childhood there and in Brittany; he settled in Paris in 1939. His work traces an ongoing metaphysical inquiry, sparked by a dark humor amid the ruins of language. Life is a death sentence, his characters are constantly reminded, and yet there is light. A strange order reigns in the world of his theater, subverting the social order with the faithfulness of dreams.

The following interview took place over several afternoons at Ionesco’s Montparnasse apartment in late March 1987. The Théâtre de la Huchette in Paris had recently celebrated the thirtieth consecutive year of its productions of The Bald Soprano and The Lesson, just as Joseph Chaikin was preparing a new production of Ionesco’s first play in New York.

It seems that through all your work, except for the polemical writings, you show little interest in realism.

Realism is a school, after all, like romanticism and expressionism, and it is not the expression of reality. Because reality does not exist. We don’t know what it is. No man of science, no physicist, can tell you what is real. So, like Mircea Eliade, I say that the real is the sacred. And I give much more importance to the imaginary world than to realism, as we call it. The realist writer, novelist, or playwright, is never “honest.” He is honest but at a certain level he is not. Because he is engaged, because he always has a tendency to express his ideology. The realist writer is biased. But the poet is not biased; the poet does not invent, he imagines. So one lets the imagination billow forth, and in the imagination the poet carries along all sorts of symbols, which are the profound truths of our soul. Of our unconscious, as it is called now, but I call it the extraconscious.

Were you never tempted to take, for example, a story or an episode from your lived life and transform that into writing?

Oh, it’s transformed in such a way that it is unrecognizable. Because I use my dreams a lot in writing, and the dream is a drama. When we dream we are always in character. As Jung said, the dream is a drama in which the dreamer is at once author, actor, and spectator. And dreams are much more profound than what we call reality. The truth of the soul, our truth, the human truth, is found more in dreams. That’s something the German poets, whom I know poorly, were well acquainted with, that is, Holderlin, Novalis, Hoffmann, Jean Paul (Johann Paul Friedrich Richter). Among the French, it’s Nerval.

Regarding dreams, do you often remember them? Do you write them down much?

I’ve had a number of experiences concerning them. Many of my plays come out of dreams, like The Killer or Journeys among the Dead, the last play I wrote. And even The Bald Soprano. Amédée is the dream I had of a cadaver that I saw in a large dark hallway of an apartment where I lived. In other plays, too, there were apparitions from dreams but, as in Amédée, the language was more or less rational, conscious. In my last plays, though, especially the last one, the language tries to stay close to the language of dreams and correspond to the image, so that the language is deteriorated, invented, assonant—an oneiric language. The characters change: one moment they’re this and another they’re that, as in a dream. And that hasn’t always been understood. At the start, I used images from dreams that I put in a play which was more or less realist. Later, I tried to use both the oneiric image and the oneiric language. My last play is in full oneiricism, a language that isn’t a rational language. At the start, I used images from dreams because they were images that came back to me from dreams. Later, I learned to remember things I had dreamed. Apparently Novalis knew how to remember his dreams. I learned how from a professor in Zurich. But since then, I’ve forgotten a bit how to remember my dreams because I haven’t applied that method anymore. All the same, I think that dreams do come through, especially in the painting I do.

They pass through unconsciously.

Yes. When I see the image that I have written, I recognize the dream, the phantasms.

How did you learn to remember your dreams?

At the clinic in Zurich when the machine showed I was dreaming they would wake me up and say, “What did you dream?” After that, I got into the habit of remembering. You can remember your dreams if you are educated to.

Were you writing down your dreams?

No. I dictated my plays to a typist. I was in an armchair, and I let the unconscious or preconscious or half-conscious images from the dreams rise up.

During the writing itself.

During the writing itself. I dictated my dreams. And since many of my plays spring from dreams, then if I am doing autobiography, it’s a dreamed autobiography. That is, I remembered my old friends, my old enemies, especially people who were dead. I made them live again and I lived along with them; an action was realized that had been inspired on contact with my dreams. That is not at all French. Because the French write lucidly, and Beckett, too. He writes lucidly and doesn’t leave the way open to the irrational. But I did.

So one must have confidence in the irrational.

Yes. I’ve always thought that dreams are not silly. In dreams are solitude and contemplation. We can reflect more truly there than in real life. There is a lucidity of dreams that is, we can’t say superior or inferior but, more penetrating.

I emerge from the dream when I write, so the work appears fresh with the water of the dream, if I can say that, mingled with reality. Reality surprises it and snatches it up.

Yet it is dreams that tend to subvert reality.

Literary critics imagined with The Bald Soprano, for example, that I had written it to scare the bourgeoisie, to parody bourgeois theater, to make a sort of politics. In reality, especially with my first plays, they have no political application whatsoever. I didn’t write The Bald Soprano while dreaming; I wrote it in a fully lucid state, but taking special care to de-signify, to remove all meaning from things, words, characters, the action. So, in removing all meaning, one returned to a dream state, we could say. And to a sort of contemplation in spite of oneself.

On various occasions you have spoken of your sense of amazement before the world.

I have felt that since childhood. My course, if we can call it such, has been the following. First, I’m born into the world, born consciously. I look at the world and my first question is, Why the world? What is all that which surrounds me and why is there something rather than nothing? This something appears absolutely miraculous to me. We have difficulty accepting the world’s presence, but we accept it. It’s there, the world is there, and still we don’t know very well if it is there, because it could collapse from one moment to the next, it could deteriorate, it could not be. I am not sure that there is something, but finally it seems there may be. Once we admit the world’s existence, the world’s presence, we pose the second question: Why is there more evil than good? In such plays as The Bald Soprano, everything is de-signified. It’s a piece that has the structure of a play, with a slow moment, a faster one, then a great movement that is very dramatic. The people argue, quarrel, fight, we don’t know why. There is no action, there are no characters. Later, with The Killer, the second question was posed: Why evil sooner than good? Those then are the two directions, the two great questions that are at the origin of my dreams, of myself.

Before The Bald Soprano, which you wrote in your mid-thirties, you’d written two earlier books in Romanian: the book of criticism, Nou (No), and the study of Victor Hugo. Had you always wanted to be a writer?

From the age of nine I said I was going to write, that I could do nothing else but write. But all the same, art leads to contemplation. And that’s what brings us closest to God, to divinity, to the extent that we can in a certain manner approach it. Especially when we do not have a religious vocation. I make literature and I write plays to pose these questions to myself in a state of wonder. Wonder is the philosopher’s first sensation, moreover, and wonder is also the beginning of contemplation, perhaps even contemplation itself. But I have written all my life, and I have done only that, from lack of a religious vocation, regretting my lack of a religious vocation and perhaps my lack of grace. But God knows whether or not I have grace. Do you believe in God?

More or less, I suppose.

Like me. So you have the sense of the sacred. And the sacred is the only reality, as Eliade said. Like everyone, I have been afraid of death, of the deaths of my friends, and of putrefaction. And we know that the sacred always subsists, it does not putrefy. It’s odd that, I think, the French do not have the sense of death. Apart from Pascal, perhaps Claudel, perhaps Péguy—but Péguy had too much literature and too much politics—the French do not have the feeling of death. They have the feeling of aging and putrefaction. One of the most beautiful French poems is “Une Charogne” (Carrion) by Baudelaire (29 in Les fleurs du Mal), where it’s putrefaction. And what is the most beautiful in Zola is not the descriptions of society, it’s not his militancy for Dreyfus. What’s most beautiful, most profound, and what he does not realize himself, is the death of Nana. Or the death of Thérèse Raquin, where we see a woman who was very beautiful, full of jewelry and full of talent, rot away and become a cadaver. They have the sense of putrefaction, but they have neither the sense of death nor the sense of resurrection.

What brought about your first book, Nou, which you wrote in your early twenties?

That book is very difficult to describe, because it is a mixture of literary politics, scandals, vanities, characters that no one knows outside of Romania. First, I realize that literature is worthless. Just as nothing is of value in the world, literature is worthless. Literature and culture are not worth anything. That is the foundation of the book, and in that book are my complaints, my regrets for a lost paradise, and the permanent search for a paradise by way of the literary meanness. All of that is very mixed together. But above all there is a question that dominates and that I posed to the most important literary critic in Bucharest, because that’s where I was: If God exists, there is not any reason to write literature. If God does not exist, there is not any reason to write literature. I have always wavered there my whole life until now, and that’s why there is derision in my work. Why write, if there is God? Why write, if there is no God? So that is the basis; that has undermined my whole literary life, my entire existence. Everything I have written is “Why write?” That’s why I have done plays where there is this question, where the characters are ridiculous, they’re derisory. My characters are not tragic because they have no transcendence—they are far from that. They are laughable. That’s why one critic called our theater “the theater of derision,” but he did not exactly know why there was derision. The derision was due to my metaphysics.

It’s as if the writing exists within that ambiguity.

Yes, mine does. The others, no, they’re poets who speak of love, of social life, of war, of politics. But even without realizing it, Brecht wrote Mother Courage, and in Mother Courage what do we see, what is most important? It’s not the war, but the presence of the canteen woman. They said it was an antiwar play, but I think it was a criticism of life. The canteen woman’s children die, she gets older and older; it’s decrepitude, old age, and that is what the truth is. He speaks of the Thirty Years’ War, but he is speaking of something other than the Thirty Years’ War. Unintentionally. That’s why I've said that the great poets wanted to make propaganda, lots of great poets. Arthur Miller, but Arthur Miller does not arrive at metaphysics. Lots of writers think they are speaking of one thing; in reality it’s something else they are thinking. Consciously or unconsciously.

In the United States a certain realism forms the main literary tradition, which of course includes Arthur Miller. But there are others, such as Robert Wilson in theater, whom you have expressed interest in.

I’ve seen two or three of his plays: Deafman Glance, another in Berlin, and another in Paris which I’ve forgotten the name of. It lasts twenty-four hours: the audience comes for two, three, four hours, then they leave, they come back. The actors barely move, they barely move. It’s a derision of theater, but it’s a derision of life, of man. Above all, it’s a derision of action. That’s why I like very much the book by Jan Kott, Shakespeare Our Contemporary, where he shows the following: A mean, corrupt, vicious prince is in power. Another young prince, to make the world just, kills the mean prince. He in his turn ages, grows corrupt, vicious, criminal. So another young prince comes to take his place. He becomes in his turn vicious, corrupt, etcetera. So another young prince, and so on. And for him it’s both a criticism and an explanation of Shakespeare’s theater. We see the kings killing each other off, and he compares that with Stalin.

What has been going on in history for the last two centuries? There was the rule of the nobles, which was based on inequality and privilege. They kill the nobles and install the bourgeoisie, a society where the child works fourteen hours a day, where people die in misery much more than in the time of the nobles. Later, man is exploited. They say that man must not be exploited, so the revolutionaries make a new regime, which is the Stalinist regime, where the privileges are greater still. Not only that, but what is serious about man is that justice truly signifies injustice, punishment. Freedom means privilege. And so the meaning is now known to us, but it took us some time to know it. This immense chaos that I try to interpret, to speak of a bit—Shakespeare had spoken of it long before me. Life “is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” If I write a theater of the absurd, I can say that my grandfather was Shakespeare.

In Notes and Counter Notes, speaking of the avant-garde, you said that the avant-gardists “finally merged into the theatrical tradition and that is what must happen to every good avant-gardist.” The same thing has happened with you. Has that bothered you in any way?

I think I’ve become a classic: they study me in schools. But I think that people can recognize the truth of what I said initially and be moved. Besides, the young people who come to the theater now don’t laugh anymore. Twenty years ago they laughed a lot, but now they’re a bit frightened before these words that don’t say anything, that do not signify, that don’t want to signify.

In 1970 you entered the Académie Française. Did that in any way change your work as a writer?

Not at all. That had no importance. It had only an external importance, and that was entirely temporary. I saw people at the Académie who came in wheelchairs or who limped, and I told myself, that’s what the truth is, and that is what will happen to me, too. Indeed, now I have a cane. But it does help, since we live on several levels of consciousness. In the least lucid consciousness, we are glad to have a nice house, and we are glad that other men give us their respect. Entering the Académie is the respect that people have for you. So why refuse it? Finally, we don’t refuse, we accept, as we accept living, as we accept earning a little money. As one accepts living, because one does not commit suicide every day. So we continue to live in a world that is our own and that is absolutely infernal. Swedenborg said that we already live in hell. And I believe that we already live in hell. Not only because there is war on every side, not only because there are earthquakes, but even if there weren’t, we already live in hell, at the furthest gate from paradise, if one believes in that. I wonder how I would live if I didn’t have the hope, even uncertain, of paradise. I’m still living, I don’t kill myself, because God forbids me to, because one hopes in spite of everything, one hopes without hoping, a mixture of belief and disbelief, one hopes for the hereafter, the resurrection of the dead. And the glorified body that never grows old. But it’s hard to put up with life.

How do you regard the development of your theater career?

There have been several periods in what I’ve written. There was the period of The Bald Soprano, in which I shattered the language joyfully. That gave me a feeling of enormous freedom, I could do whatever I wanted with words. Through the middle period, Exit the King, there was hope, there was still God. But later, with time, the breakage of language grew heavier, it became tragic. That’s what we see in my last play, Journeys among the Dead, where there are a lot of ghosts, dead people with whom I speak. In the end, the theatrical game disappears and there is a return to a certain metaphysics. Perhaps with God, perhaps without God, I myself don’t know.

Do you feel that your plays became more and more oriented toward the spiritual?

The Bald Soprano is a spiritual play. Because it is my wonder before the world. In my first play I am amazed by the fact that there are people who exist, who speak, and I don’t understand what they’re saying, I don’t know. In the second play, The Lesson, there is a play on words with death at the end. In The Chairs, it’s metaphysics—there was that mixture of metaphysics and moral ideology. All the time there was this mixture, and the critics didn’t understand. In Exit the King, you have an end that was inspired by the Tibetan dialogue of the dead. At the end the king dies, he loves life, he doesn’t want to die. Then comes resignation, and after that, a spiritual guide who is the queen leads him toward the hereafter, according to the Tibetan rite. “Don’t touch the flower, let your saber drop from your hand, do not fear the old woman who will ask you” I don’t know what. Go up, go up, go up. In the Tibetan rite of death, women surround the dying man or even the recently dead, and they tell him, “Rise, rise, rise,” so that he doesn’t fall into the lower regions, the infernal regions. So the king’s end was inspired by that.

Has the audience become increasingly open to your theater?

At first, they were for me. There were the critics at Le Figaro who were opposed, the latecomers, the imbeciles. And then the young critics were for me, but they were Marxists. So when they understood that I was not a Marxist—I said so, I shouted it—at that point they turned away from me. And the backward critics who had attacked me, they said, “He’s not a leftist, so he’s one of us!” At the start they had said, “Dirty theater, bad theater, detestable theater”; now they said, “Good theater, admirable theater, Exit the King is like Shakespeare,” and other foolishness. Now there’s a return toward me of those who were and are no longer Marxist.

Does it seem that audiences are less confused by your work than they used to be?

With The Bald Soprano, which for me was a tragedy of language, they did not understand. With other plays they understood, but poorly. They understood politically. At first, they were very favorable toward Rhinoceros, because they said, “Now there’s a fine criticism of Nazism.” I had considerable success in Germany. Later, when (Jean-Louis) Barrault’s theater did a revival of Rhinoceros some years ago, it became suspect again, because the people of the left who had said that it’s a criticism of Nazism said, “But what if it’s a criticism of us?” Because it is an antitotalitarian criticism.

So people insisted on being very simplistic about it.

You know, Rhinoceros was a great success the world over. It was played in Spain during Franco’s time, because they said the rhinoceroses are the communists. It was played to great success in Argentina. Perón had fallen and they said it’s an anti-Peronist play. The play was able to be performed in the countries of the Eastern bloc, because they said it is an anti-Nazi play. In Germany they said it’s an anti-Nazi play and that was true, they felt it. But the play was performed in England. At the time, England was a tranquil country—it is no longer a tranquil country. I said to my producer, “The English will have a hard time understanding this play because there was no civil war in England.” In France there were Nazis and patriots, there was the Dreyfus case, with the Dreyfusard and the anti-Dreyfusard. So my producer told me, “Listen, I managed to get you Laurence Olivier as the leading actor, I managed to get you a great director,” which was Orson Welles, “I got you a great theater. Excuse me if I couldn’t get you the civil war in England.”

It seems that everyone wanted only to see their own story in it.

I had asked some young people who hadn’t known Nazism and who hadn’t known communism, the Austrians for example. The theater there was more than full, many many people came in Vienna, and I asked, “Here it is, this is a play in my antitotalitarian spirit. What do you understand now, what is it for you?” And they said, “But it’s clear, for us it is an anticonformist play,” against conformism. So, the play continues to exist.

Has the writing changed much for you over the years?

Oh, I think my plays are very different from each other. Perhaps I boast, but my plays, most of which have not been inspired by any other play, always change, it’s always something else. I went to England recently with my play Journeys among the Dead, at the Riverside Theatre, and the English were very surprised. Apart from nonprofessional companies, my plays had not been performed in England in a long time, because I was against Brecht. The public came en masse; the first nights were full. Then after, the other nights were empty. Because they thought they were going to find an Ionesco who would have made them laugh, an Ionesco like that of The Bald Soprano, for example. I came on at the end and explained my new play to them. So they came back to the theater. But except for the Sunday Times and the Observer, the reviews were bad. They didn’t recognize me anymore.

What about the act itself of writing? Your earliest plays are often dated at the end by the month they were written. That means you wrote it entirely in a month?

Yes. Three weeks or a month.

Did you have to do several drafts?

No. They came out very quickly. A few tiny details I changed, but I wrote them like that. Then I read them over. And when I had a secretary, I dictated to her at the machine. I hardly ever change it.

You’ve always worked like that?

Always.

Even the longer plays?

Even the longer plays, I never change them.

So what brings you to the point of writing? Do you prepare much, do you take notes?

No. I think about a dream, or else I sit down and wait for the characters to speak. And when I’ve heard an exchange of replies between two characters, then I continue.

Do you sense from the start that it will be one act or two or three acts, do you feel the scope of it?

Yes, more or less. I have no preliminary idea when I write, but as I write my imagination completes it. So the second half or more of the play takes shape in my head. Then I know how I’m going to end it. Though I must say that spontaneous creation does not exclude the pursuit and consciousness of style.

Have you ever been tempted to act in one of your plays?

I acted in a film, La vase (The Mire). I was the only character.

Do you work much with the directors of your plays?

Usually when it’s in Paris I work with my directors. The play is developed with the director, by way of squabbling. I take the play away, I give it back again, I take it away, and so on. Especially with Jean-Marie Serreau it happened like that, and with Sylvain Dhomme as well, with The Chairs. I hate when they ignore my stage directions. But when I do the play myself, be it Exit the King or Victims of Duty, which I like a lot, then I myself don’t respect my own stage directions.

Have you learned certain things now and then from the actors?

I have never written for actors. And you must pardon my pride but actors have not affected my plays. The actors are characters that come out of my mind and who must conform to what I have seen in my mind.

I have heard that you travel a lot.

Yes, more and more. California, the United States, the East Coast, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, China, Taiwan, Japan, Senegal, and a lot to Israel. Because I adore Israel. And perhaps sometimes I’ve been such an adept of Israel that now, when I see Arafat, the leader of the Palestinians, now I wonder if I shouldn’t have been a bit more balanced. Because he is unhappy, his people are being killed. But I did not want the Jews to be killed. Because if we hadn’t supported them they would have been destroyed by forty Arab countries. So it was necessary to be on their side, and now it’s necessary to think of the others too, a bit. But I do not understand this rage that exists in Lebanon, in Syria, in Iran, in Iraq, in Thailand, in Vietnam, in the entire world. When I think that it goes back not a hundred years but a thousand years, and not a thousand but ten thousand years, and that it has always been like this, I am absolutely terrified. I tell myself, this world is hell, but hell has no end! Everyone is killing each other. Jesus said, “Love one another,” and it’s as if he had said, “Kill one another.”

Are you superstitious?

Yes, a lot. I believe, for example, that in my last play I mistreated some dead people, some ghosts. My father, who is dead, my step-mother, my grandmother. And I believe that some rather terrible things happened to me because of that. I have other reasons to believe in the immediate unreality because those dead people, in my opinion, are there for some time, and at the end of several centuries they go away. I’ve had strange dreams. For example, I was in England at a friend’s house. I slept in a room there and at night I dreamed that I was surrounded by doctors with white blouses who told me, “We’re going to operate on your brain. It’s not fun, but it’ll be all right, it’ll pass.” And then the doctors leave, only one remains, and I say to him, “Tell me the truth, doctor. I have a brain tumor, don’t I? It’s incurable, and that’s why you don’t want to operate on me anymore?” And he tells me, “Yes, go back home to the country.” The country meaning a friend’s house there. So I woke up, it was dawn, and I walked about from one place to another to see if I knew my direction. Because I had been told that in many cases, those who have a malignant brain tumor lose their sense of direction. My wife wakes up and says to me, “But what’s wrong with you? You’re crazy. Why are you running around the house like that?” I tell her my dream and she says, “It’s nothing, just a story.” Morning comes, we go to breakfast in the dining room. My daughter slept in the room next to us; she arrives and says, “Oh, Papa, you snored last night, a lot.” I tell my daughter, “No, that’s not true, I wasn’t snoring.” Our hostess is frightened, and she says, “Yes, yes, my little girl, it’s your father who was snoring.” All right. My daughter goes out to play, and our hostess says, “Excuse me, it’s not you who was snoring. It’s my grandfather. My grandfather died eight years ago; it’s the anniversary today. Each year on his anniversary we hear his death-rattle.” So I say to our friend who was putting us up, “I know what he died from, your grandfather. He died from a malignant brain tumor. They wanted to operate; as it was incurable they sent him home.” “How do you know?” “I dreamed it.” But I’ve had a lot of other experiences.

There is also a prophetic aspect to dreams.

Yes, the night before my mother’s death—I’m in the process of writing about her death at the moment—that night I saw her amid flames. I wanted to pull her away; I wasn’t able to. The next day she was dead, from brain stroke. And then I’ve had premonitions. During the war I went to Bucharest one year to arrange my military situation. One night I wake up, I say, “Earthquake!” My wife wakes up, completely terrified. There was no earthquake, there wasn’t anything. So we go back to sleep. The next night I wake up. “Earthquake!” My wife says, “But you’re crazy.” And then she feels that everything’s moving. It was true.

What else do you know of ghosts?

There are ghosts in Brittany, but very few. There were a lot in my childhood, because I grew up near Brittany, in the Mayenne region exactly. There were ghosts. There aren’t any more now. They’ve all taken refuge in England.

How do you know?

By the dream I had. And our friend there, in Maidenhead, told us other stories of ghosts as well. Apparently there are still some in Gascony, very few.

I wonder how people can follow their route.

I don’t know, especially how they manage to cross the channel. Because apparently ghosts don’t travel through water. Perhaps on a boat.

In Fragments of a Journal you noted at one point, which you come back to several times, “Once again the dream that explains everything, this dream of the absolute truth, has escaped me.” Do you think that such a dream, or the substance of such a dream, could ever be apprehended?

It’s a hope that is chimerical, metaphysical. It’s a hope for illumination. But it’s not a psychological hope, not realistic.

You also like to cite the example of what the Zen monks discovered, when after a long search for illumination they end up reaching a sort of divine laughter before the illusion of the world.

But I hoped to have this illumination in a dream. I felt that perhaps there would be one of these dreams that could explain everything, everything. It’s a mythical way, an absolutely unreal way to explain.

Various people have spoken about guiding their own dreams.

Yes, that exists. With the romantic poets, Jean Paul, Novalis, Hoffmann, I think. But I’m not able to control my dreams. I never knew how.

You’ve spoken of the crisis of contemporary language, saying that it doesn’t exist.

No, the crisis of language, so-called, does not exist. We can express ourselves scientifically or literarily; we have enough definitions for psychology, sociology, etcetera. It’s sooner a crisis of communication between man and man. Or that’s what I think now. There is a crisis in communication that is above all emotional. I don’t know why. I think it goes way back, as with the Tower of Babel in Kafka. Men could not understand each other because first they said they wanted to reach God, and in reality from the first or second floor up they set to squabbling, for a better position or whatever. The crisis of language comes from that moment there, that mythic moment.

As if man cannot really manage to understand what is important.

Yes, that’s right. Man does not understand the essential. Not only does he not understand: he could at least feel it, and he does not feel it either. He does not know at all, not in any way, neither emotionally nor intellectually. Intellectually is impossible because we cannot understand God. Since then, I think we’ve been bent on—myself, I have been especially bent on conceiving the inconceivable, comprehending the incomprehensible, the infinitely small, the infinitely large, comprehending what is limited and what is unlimited. That is, the great mysteries in which we live cannot be, by ourselves, by our powers, understood. We can only understand them thanks to mystical intuitions. Saint John of the Cross, identifying himself in a certain way with God, Saint Thérèse de Lisieux, Saint Teresa of Avila understood. But we cannot understand; ordinary language cannot understand. We must resign ourselves to not understanding. And that is the hardest thing.

Your last play, Journeys among the Dead, seems to end by way of this resignation.

At the end of the play there is a sort of desperate attempt to understand or make oneself understood beyond words, in another language, in a sort of metalanguage, to find their meaning there where there is no meaning. Where words have lost their meaning.

The last words of that play are “I don’t know.” That recalls the words of certain writers who, after having lived their entire lives, their entire careers, arrive at this “I don’t know.”

But that is another “I don’t know.” I know. I know what the radiator is, what this or that thing is, a logical or ordinary thing. It has to do with another kind of “I don’t know,” with a sort of spiritual incomprehension, metaphysical or divine.

Does one have to live an entire life to arrive at this “I don’t know?”

Myself, I knew from the beginning. I knew it, or rather, I suspected as much.

Earlier you were speaking of arriving at something mystically, in discussing certain aspects of The Bald Soprano. Were you thinking in those terms at the time?

Yes, but in a way that was less clear. Because I was much younger. Then to the degree that I didn’t understand things, I asked myself why I didn’t understand. And then seeing that whatever I do, I would never understand, I was beset with a sort of despair. I’m like that man who said, “My God, make me believe in You.”

You’ve often said that symbols have counted a lot for you. You profoundly believe in symbols. Even in Fragments of a Journal you wrote that you believe too much in the myths of psychoanalysis.

Yes, because psychoanalysis is limited. It’s a scientific language like any other scientific language. It’s not a language that is metascientific, it’s not a metalanguage, it’s not something that goes beyond the language.

In a more recent book, you mention having seen a lot of “psychoanalysts, priests, and rabbis.” Considering the plays, and the dreams written down in your journals, what is your experience of psychoanalysis?

Not too wide. I know psychoanalysis from books and from a bit of experience. An experience of Jungian psychoanalysis where one speaks, one discusses. Where one has waking dreams. But at any rate, without God one cannot begin to grasp whatever it may be. Any psychoanalysis goes a little farther than the usual language but not a lot farther. It remains more or less on the same plane. The level where it plunges inside is very reduced, hardly profound.

Did your discussions with “the priests and rabbis” ever bring you much?

No, they didn’t teach me anything. Nothing can make a person know, only prayer. But if I knew how to pray . . . I don’t know how to pray. And they, the professional rabbis and priests, are moralists much more than anything else, much more than mystics. Saint Augustine, for example, seems to me much more a moralist than a mystic. I feel closer to Saint John of the Cross.

You’ve made occasional mention of the gnostics. Have you read them much?

Yes, and I’ve been tempted several times by gnostic thought. I was tempted by that heresy, as it is called, thinking that there is evil in the world and that God could not have been the author of this evil. So it was, as Cioran says, the evil demiurge who created this world.

The gnostics spoke of the hidden God. Did that appeal to you?

If one believes the gnostics, God is hidden. But I don’t always believe that. Sometimes I believe it; other times I feel that he reveals himself in the plenitude of his light. The plenitude of light that I do not have, but I have vaguely felt something. I speak of it in Fragments of a Journal and in the first part of The Killer, where I say I felt happy one day, infinitely happy, blissful, because suddenly, it was a spring day, I felt that I was enveloped in a light greater than the sun, and yet the sun was at its zenith. The world seemed miraculous to me. That is, the handkerchiefs and the pants hanging on the clothesline suddenly seemed dazzlingly beautiful to me. Everything was made beautiful by God’s presence; I felt myself protected by Him. But that instant was very brief, really very brief, and after fifteen minutes, or ten minutes, or five—times is not measurable in such an instant—I felt as in a dizzy fall, as if I had lost something that was the most important thing of all.

Early on you wrote that you would remember that moment for a long time after.

Yes, but I also wrote many years later that it did not have the power to reconcile me. That is, what I had learned at that moment was very little, a tiny bit that God had deigned to give me, and I had lost it, I no longer had but the memory of a memory of a memory. The thing was as if dried up, and this memory no longer warmed my existence.

What about Hunger and Thirst? That play seemed to mark a new step in your metaphysical path.

I thought so, too.

Did you feel it as such at the time?

Yes and no. It was sincere, insincere, it was true, untrue, it was an innocent game, it was an overrated game. It was truth, or it was literature, I don’t know myself. It was a search that was perhaps sincere, of the essential, but this search was not entirely honest. Unwillingly, because there was all the literature, theological and literary, that was swallowed up in there. “Hunger and thirst”: since we call them that, hunger and thirst, it denotes their falsity. That is, these are words, these are words from philosophy, from morality, from literature. I don’t think that it’s a totally true thing, but there where it was true is the vision my wife had, the character Madeleine, who sees the landscape, the garden she had seen as a six-year-old child. And I put that on the stage. And then it was a sort of confession like the others: I’m bad, here is paradise, here is hell.

The vision you were speaking of, do you mean the vision at the end, of the garden with the silver ladder suspended in the air?

Yes, it’s a bit true and a bit untrue. I had that dream. I dreamed of a thicket and of a silver ladder. Later, when I spoke of that with my friends, they told me that this archetypal dream exists. It exists in Jung and in the Bible. But I didn’t know it existed. Perhaps it was the collective unconscious that I had penetrated, in which I had rummaged, and from which I had brought back certain things.

That vision reappears at the end of your novel The Hermit as well.

Well, there I think it’s on purpose. What is true in there is the nonsense of all action, the stupidity, the absurdity of politics, of war. And the end was laid right over that. But I have often wondered how it is that for thousands and thousands of years it continues, always the same; it’s war that continues. And I’ve wondered, perhaps committing heresy, how it is that God has not tired of this very long story without end. Endlessly ending. And it’s always the same thing, the same devouring hate between people. Or the same need for love that is always betrayed and that has never really existed in the end. Because do people truly love each other?

That corresponds a little with an aspect of Hunger and Thirst. Several times there you play with the idea of pity. For example, in the second act, “The Rendez-Vous,” the Second Guard says, “Each person demands it for himself, none is able to give it to others.”

Yes, that’s true. It does exist, as in the story of Father Kolbe. He was a Polish Catholic priest who had been at Auschwitz in a concentration camp. A prisoner had escaped, so they chose a group who for fifteen days would live without food or drink if the prisoner did not return, to die of hunger and thirst. Father Kolbe was not among them; he was in the camp because he was Catholic and because he irritated the Nazis. Among those who were designated, one was crying. Father Kolbe asked the commander of the camp, “I want to go in his place.” He went in his place, and there he lived among them for fifteen days, and after fifteen days he died. But he died after all the others, he helped the others die for fifteen days, and at the end he stretched out his arm for them to give him an injection, because in spite of his weakness he still didn’t die. Now there is someone who loved others more than himself. But I know of no other case. Or yes, Jesus, of course. But apart from Jesus and a few saints, I don’t think so. I think that some old folks, to live a few days longer still, would sacrifice the lives of children.

But in the end I am a man like all men and less courageous than many other men. Much more cowardly, as intellectuals often are; much more bourgeois. I would not make Kolbe’s sacrifice. And at the same time I’m thirsty for glory. So everything in me is absolutely imperfect.

Has there been a certain disappointment for you in becoming famous?

No. I wanted fame, I wanted to escape anonymity. Existence in anonymity seemed inadmissible to me. I did not want to live in anonymity because I told myself that if I cannot live in God—living in God means to live in silence, in monastic life—then to live at least shining among men. I know that is an error, but I can’t help it.

At what point did you realize you wanted fame?

Right away. When I started writing. When I was a child, when I was ten, eleven, twelve, I told myself, “I would like to be a saint.” But one should not want to be a saint, one should be a saint. To want to be a saint is to want glory. Then I wanted to be a general. But being a general is first to brave danger, and it is also to want glory. So, not able to be a saint, not able to be a general, at least be a writer. I have the desire for and a mistrust of glory.

The problem for me was choosing between God and men. Not in order to love men really, but above all to shine among them. Which Saint Augustine condemned. So I chose men. And when one chooses men, one is often against God. It is a titan’s attitude. But when one chooses God, one loves men as well. Like Saint Thérèse de Lisieux, who cried thinking of the misfortunate ones in hell.

You worked for quite a while as a teacher. Have you sometimes felt as a writer that you are still a teacher?

No. I don’t want to teach anything. I don’t propose a message. I propose, in the least ignoble part of me, in the noble part of me, I pose questions, problems, and I have no solutions. The solutions are automatic, political, ideological; the solutions are not each person’s quest. Whereas if one poses the problem to each one of thousands or hundreds of spectators, each one of the spectators, though there be hundreds, becomes one again, a character, alone, like Bérenger in Rhinoceros. Bérenger was written to try to teach even so—you see, I contradict myself. But it’s the only play with a message, to try to give men the belief that they can think for themselves, the power to think for themselves outside of others, but I did not say who the others were. They were the Nazis, the conformists, the communists, I don’t know who else. To make people understand that they could live alone, in solitude. As I myself managed to when I was young, in Romania, where I was neither communist nor Iron Guard. So it is and it is not a didactic message. It’s not didactic because I’m telling about my experience. I expose the problem not so much for people to respond to each other about it but so that they can respond to me and give me a voice.

That image at the end of your novel The Hermit, with the garden and the silver ladder, which is more or less the same image at the end of Hunger and Thirst, it seems to give a bit more hope in the novel.

Yes; that is not hope, it’s the desire to have hope. It’s between literature and truth. But it is the sincere desire to have hope, the regret of not having had it, and I would have liked to give hope to this imaginary hero who is the hermit.

In your later plays was it sometimes difficult to show images that were too deeply linked to your own life?

No, I have no presumptions, I have no shame. Literature is without shame. It is “the heart laid bare” of Baudelaire. On the contrary, what I look for in literature is to be more and more true, more and more close to myself, and so more and more immodest.

What was the response to your play The Man with the Luggage?

The Man with the Luggage was a political play, so it was very poorly received. It was a political dream, a nightmare. I dreamed that I found myself in my native land and that I could not leave, and that it was a totalitarian country. So right away, with the left, which was very strong in France at that time, it was poorly considered, because it was a criticism of a totalitarian regime.

What was your experience with the productions of Journeys among the Dead?

The play was performed in France, Germany, and England. In France it was well received I think only because the director was a man of the left. It was poorly received in Germany because it was not a play of the left. There were other reasons too—simply that they didn’t understand what it meant.

Have you written other plays since Journeys among the Dead?

I started a play about Kolbe, the priest in the concentration camp, but it hasn’t worked. I wrote one act; it’s a rather conventional play. But I think about writing other plays still.

In Claude Bonnefoy’s book of interviews with you, Entre la vie et le rêve, you spoke of the style de lumière of certain writers. Whom did you have in mind?

I was thinking of Charles du Bos, of Valery Larbaud, perhaps others. I felt that their writing had a certain luminous spark; the words were luminous. But it was a very subjective impression.

Did the futurists interest you?

The futurists, the dadaists, the surrealists, yes, somewhat. Soupault, Breton, Tzara, Marinetti, I knew all that. But I haven’t been influenced by playwrights. I parodied Shakespeare, that is, I parodied him in trying to add something, the problem of politics, in Macbett. I’ve been influenced by writers like Dostoyevsky and especially Kafka.

How did Kafka influence you?

I couldn’t say exactly what form that has taken, because it’s an influence where the bigger it is, the less explainable it is. But I have felt it in myself, and I have admired him very much. And on another level, I’ve been influenced by Baudelaire.

Did Picasso’s theater work interest you?

A bit, yes, I liked it. Because it was a theater that was a bit absurd. Philosophical, more so than mine, and absurd at the same time.

In Antidotes, the book of articles and essays, you wrote that Denis de Rougemont and Jean Grenier “could be the authentic thinkers of our time.” How so?

On the level of politics and on the level of morality. On the level of religion they were believers, but they weren’t believers like Kafka, for example. In that sense, Kafka reinvented religion because he lived it in an entirely internal manner, whereas Denis de Rougemont or Jean Grenier lived it in an external way, rather practical. With Kafka it was a living faith, an ardently spiritual life, and I don’t know even if he himself knew that he believed.

And where were de Rougemont and Grenier politically?

They were anticommunist and anti-Nazi.

The women characters are usually very crucial in your plays. It’s been said that you are one of the better writers for women. Does that correspond to your intentions?

They have a great importance. I’ve written for women and against women. The Painting is antifeminist. But Hunger and Thirst is for women. Also a play like A Stroll in the Air, where I try to explain the distress of the woman, her solitude. Amédée is against women, because they are sometimes crabby and tough, but at the same time it is for them, because the woman there is the one who does all the work, she’s the one who puts up with everything. Who even puts up with a man, which is not easy. Like the character, and like myself. But in the end the man-woman question doesn’t really enter my theater.

published in City Lights Review (San Francisco) 3 (Nov. 1989), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (1991), now out of print

It was with his first play, La cantatrice chauve (The Bald Soprano), in Paris 1950, that Eugène Ionesco (1909-1994) became famous. One of the leading dramatists in the “theater of the absurd,” as critics billed it, Ionesco followed with The Lesson, The Chairs, Rhinoceros, Exit the King, as well as more plays, short stories, theater criticism, journals, polemics, and a novel. His last play, Journeys among the Dead, was written in 1980.

Since then, he has also returned to painting, which he first took up over ten years earlier. “Painting retaught me the taste for writing by hand,” he says. In 1988 he published La quête intermittente, which he describes as “autobiographical reflections, flashes, thoughts, meditations, different things, and the quest is intermittent because it is the quest for the absolute.”

Born in Romania in 1909 of a French mother, Ionesco spent his childhood there and in Brittany; he settled in Paris in 1939. His work traces an ongoing metaphysical inquiry, sparked by a dark humor amid the ruins of language. Life is a death sentence, his characters are constantly reminded, and yet there is light. A strange order reigns in the world of his theater, subverting the social order with the faithfulness of dreams.

The following interview took place over several afternoons at Ionesco’s Montparnasse apartment in late March 1987. The Théâtre de la Huchette in Paris had recently celebrated the thirtieth consecutive year of its productions of The Bald Soprano and The Lesson, just as Joseph Chaikin was preparing a new production of Ionesco’s first play in New York.

It seems that through all your work, except for the polemical writings, you show little interest in realism.

Realism is a school, after all, like romanticism and expressionism, and it is not the expression of reality. Because reality does not exist. We don’t know what it is. No man of science, no physicist, can tell you what is real. So, like Mircea Eliade, I say that the real is the sacred. And I give much more importance to the imaginary world than to realism, as we call it. The realist writer, novelist, or playwright, is never “honest.” He is honest but at a certain level he is not. Because he is engaged, because he always has a tendency to express his ideology. The realist writer is biased. But the poet is not biased; the poet does not invent, he imagines. So one lets the imagination billow forth, and in the imagination the poet carries along all sorts of symbols, which are the profound truths of our soul. Of our unconscious, as it is called now, but I call it the extraconscious.

Were you never tempted to take, for example, a story or an episode from your lived life and transform that into writing?

Oh, it’s transformed in such a way that it is unrecognizable. Because I use my dreams a lot in writing, and the dream is a drama. When we dream we are always in character. As Jung said, the dream is a drama in which the dreamer is at once author, actor, and spectator. And dreams are much more profound than what we call reality. The truth of the soul, our truth, the human truth, is found more in dreams. That’s something the German poets, whom I know poorly, were well acquainted with, that is, Holderlin, Novalis, Hoffmann, Jean Paul (Johann Paul Friedrich Richter). Among the French, it’s Nerval.

Regarding dreams, do you often remember them? Do you write them down much?

I’ve had a number of experiences concerning them. Many of my plays come out of dreams, like The Killer or Journeys among the Dead, the last play I wrote. And even The Bald Soprano. Amédée is the dream I had of a cadaver that I saw in a large dark hallway of an apartment where I lived. In other plays, too, there were apparitions from dreams but, as in Amédée, the language was more or less rational, conscious. In my last plays, though, especially the last one, the language tries to stay close to the language of dreams and correspond to the image, so that the language is deteriorated, invented, assonant—an oneiric language. The characters change: one moment they’re this and another they’re that, as in a dream. And that hasn’t always been understood. At the start, I used images from dreams that I put in a play which was more or less realist. Later, I tried to use both the oneiric image and the oneiric language. My last play is in full oneiricism, a language that isn’t a rational language. At the start, I used images from dreams because they were images that came back to me from dreams. Later, I learned to remember things I had dreamed. Apparently Novalis knew how to remember his dreams. I learned how from a professor in Zurich. But since then, I’ve forgotten a bit how to remember my dreams because I haven’t applied that method anymore. All the same, I think that dreams do come through, especially in the painting I do.

They pass through unconsciously.

Yes. When I see the image that I have written, I recognize the dream, the phantasms.

How did you learn to remember your dreams?

At the clinic in Zurich when the machine showed I was dreaming they would wake me up and say, “What did you dream?” After that, I got into the habit of remembering. You can remember your dreams if you are educated to.

Were you writing down your dreams?

No. I dictated my plays to a typist. I was in an armchair, and I let the unconscious or preconscious or half-conscious images from the dreams rise up.

During the writing itself.

During the writing itself. I dictated my dreams. And since many of my plays spring from dreams, then if I am doing autobiography, it’s a dreamed autobiography. That is, I remembered my old friends, my old enemies, especially people who were dead. I made them live again and I lived along with them; an action was realized that had been inspired on contact with my dreams. That is not at all French. Because the French write lucidly, and Beckett, too. He writes lucidly and doesn’t leave the way open to the irrational. But I did.

So one must have confidence in the irrational.

Yes. I’ve always thought that dreams are not silly. In dreams are solitude and contemplation. We can reflect more truly there than in real life. There is a lucidity of dreams that is, we can’t say superior or inferior but, more penetrating.

I emerge from the dream when I write, so the work appears fresh with the water of the dream, if I can say that, mingled with reality. Reality surprises it and snatches it up.

Yet it is dreams that tend to subvert reality.

Literary critics imagined with The Bald Soprano, for example, that I had written it to scare the bourgeoisie, to parody bourgeois theater, to make a sort of politics. In reality, especially with my first plays, they have no political application whatsoever. I didn’t write The Bald Soprano while dreaming; I wrote it in a fully lucid state, but taking special care to de-signify, to remove all meaning from things, words, characters, the action. So, in removing all meaning, one returned to a dream state, we could say. And to a sort of contemplation in spite of oneself.

On various occasions you have spoken of your sense of amazement before the world.

I have felt that since childhood. My course, if we can call it such, has been the following. First, I’m born into the world, born consciously. I look at the world and my first question is, Why the world? What is all that which surrounds me and why is there something rather than nothing? This something appears absolutely miraculous to me. We have difficulty accepting the world’s presence, but we accept it. It’s there, the world is there, and still we don’t know very well if it is there, because it could collapse from one moment to the next, it could deteriorate, it could not be. I am not sure that there is something, but finally it seems there may be. Once we admit the world’s existence, the world’s presence, we pose the second question: Why is there more evil than good? In such plays as The Bald Soprano, everything is de-signified. It’s a piece that has the structure of a play, with a slow moment, a faster one, then a great movement that is very dramatic. The people argue, quarrel, fight, we don’t know why. There is no action, there are no characters. Later, with The Killer, the second question was posed: Why evil sooner than good? Those then are the two directions, the two great questions that are at the origin of my dreams, of myself.

Before The Bald Soprano, which you wrote in your mid-thirties, you’d written two earlier books in Romanian: the book of criticism, Nou (No), and the study of Victor Hugo. Had you always wanted to be a writer?

From the age of nine I said I was going to write, that I could do nothing else but write. But all the same, art leads to contemplation. And that’s what brings us closest to God, to divinity, to the extent that we can in a certain manner approach it. Especially when we do not have a religious vocation. I make literature and I write plays to pose these questions to myself in a state of wonder. Wonder is the philosopher’s first sensation, moreover, and wonder is also the beginning of contemplation, perhaps even contemplation itself. But I have written all my life, and I have done only that, from lack of a religious vocation, regretting my lack of a religious vocation and perhaps my lack of grace. But God knows whether or not I have grace. Do you believe in God?

More or less, I suppose.

Like me. So you have the sense of the sacred. And the sacred is the only reality, as Eliade said. Like everyone, I have been afraid of death, of the deaths of my friends, and of putrefaction. And we know that the sacred always subsists, it does not putrefy. It’s odd that, I think, the French do not have the sense of death. Apart from Pascal, perhaps Claudel, perhaps Péguy—but Péguy had too much literature and too much politics—the French do not have the feeling of death. They have the feeling of aging and putrefaction. One of the most beautiful French poems is “Une Charogne” (Carrion) by Baudelaire (29 in Les fleurs du Mal), where it’s putrefaction. And what is the most beautiful in Zola is not the descriptions of society, it’s not his militancy for Dreyfus. What’s most beautiful, most profound, and what he does not realize himself, is the death of Nana. Or the death of Thérèse Raquin, where we see a woman who was very beautiful, full of jewelry and full of talent, rot away and become a cadaver. They have the sense of putrefaction, but they have neither the sense of death nor the sense of resurrection.

What brought about your first book, Nou, which you wrote in your early twenties?

That book is very difficult to describe, because it is a mixture of literary politics, scandals, vanities, characters that no one knows outside of Romania. First, I realize that literature is worthless. Just as nothing is of value in the world, literature is worthless. Literature and culture are not worth anything. That is the foundation of the book, and in that book are my complaints, my regrets for a lost paradise, and the permanent search for a paradise by way of the literary meanness. All of that is very mixed together. But above all there is a question that dominates and that I posed to the most important literary critic in Bucharest, because that’s where I was: If God exists, there is not any reason to write literature. If God does not exist, there is not any reason to write literature. I have always wavered there my whole life until now, and that’s why there is derision in my work. Why write, if there is God? Why write, if there is no God? So that is the basis; that has undermined my whole literary life, my entire existence. Everything I have written is “Why write?” That’s why I have done plays where there is this question, where the characters are ridiculous, they’re derisory. My characters are not tragic because they have no transcendence—they are far from that. They are laughable. That’s why one critic called our theater “the theater of derision,” but he did not exactly know why there was derision. The derision was due to my metaphysics.

It’s as if the writing exists within that ambiguity.

Yes, mine does. The others, no, they’re poets who speak of love, of social life, of war, of politics. But even without realizing it, Brecht wrote Mother Courage, and in Mother Courage what do we see, what is most important? It’s not the war, but the presence of the canteen woman. They said it was an antiwar play, but I think it was a criticism of life. The canteen woman’s children die, she gets older and older; it’s decrepitude, old age, and that is what the truth is. He speaks of the Thirty Years’ War, but he is speaking of something other than the Thirty Years’ War. Unintentionally. That’s why I've said that the great poets wanted to make propaganda, lots of great poets. Arthur Miller, but Arthur Miller does not arrive at metaphysics. Lots of writers think they are speaking of one thing; in reality it’s something else they are thinking. Consciously or unconsciously.

In the United States a certain realism forms the main literary tradition, which of course includes Arthur Miller. But there are others, such as Robert Wilson in theater, whom you have expressed interest in.

I’ve seen two or three of his plays: Deafman Glance, another in Berlin, and another in Paris which I’ve forgotten the name of. It lasts twenty-four hours: the audience comes for two, three, four hours, then they leave, they come back. The actors barely move, they barely move. It’s a derision of theater, but it’s a derision of life, of man. Above all, it’s a derision of action. That’s why I like very much the book by Jan Kott, Shakespeare Our Contemporary, where he shows the following: A mean, corrupt, vicious prince is in power. Another young prince, to make the world just, kills the mean prince. He in his turn ages, grows corrupt, vicious, criminal. So another young prince comes to take his place. He becomes in his turn vicious, corrupt, etcetera. So another young prince, and so on. And for him it’s both a criticism and an explanation of Shakespeare’s theater. We see the kings killing each other off, and he compares that with Stalin.

What has been going on in history for the last two centuries? There was the rule of the nobles, which was based on inequality and privilege. They kill the nobles and install the bourgeoisie, a society where the child works fourteen hours a day, where people die in misery much more than in the time of the nobles. Later, man is exploited. They say that man must not be exploited, so the revolutionaries make a new regime, which is the Stalinist regime, where the privileges are greater still. Not only that, but what is serious about man is that justice truly signifies injustice, punishment. Freedom means privilege. And so the meaning is now known to us, but it took us some time to know it. This immense chaos that I try to interpret, to speak of a bit—Shakespeare had spoken of it long before me. Life “is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” If I write a theater of the absurd, I can say that my grandfather was Shakespeare.

In Notes and Counter Notes, speaking of the avant-garde, you said that the avant-gardists “finally merged into the theatrical tradition and that is what must happen to every good avant-gardist.” The same thing has happened with you. Has that bothered you in any way?

I think I’ve become a classic: they study me in schools. But I think that people can recognize the truth of what I said initially and be moved. Besides, the young people who come to the theater now don’t laugh anymore. Twenty years ago they laughed a lot, but now they’re a bit frightened before these words that don’t say anything, that do not signify, that don’t want to signify.

In 1970 you entered the Académie Française. Did that in any way change your work as a writer?

Not at all. That had no importance. It had only an external importance, and that was entirely temporary. I saw people at the Académie who came in wheelchairs or who limped, and I told myself, that’s what the truth is, and that is what will happen to me, too. Indeed, now I have a cane. But it does help, since we live on several levels of consciousness. In the least lucid consciousness, we are glad to have a nice house, and we are glad that other men give us their respect. Entering the Académie is the respect that people have for you. So why refuse it? Finally, we don’t refuse, we accept, as we accept living, as we accept earning a little money. As one accepts living, because one does not commit suicide every day. So we continue to live in a world that is our own and that is absolutely infernal. Swedenborg said that we already live in hell. And I believe that we already live in hell. Not only because there is war on every side, not only because there are earthquakes, but even if there weren’t, we already live in hell, at the furthest gate from paradise, if one believes in that. I wonder how I would live if I didn’t have the hope, even uncertain, of paradise. I’m still living, I don’t kill myself, because God forbids me to, because one hopes in spite of everything, one hopes without hoping, a mixture of belief and disbelief, one hopes for the hereafter, the resurrection of the dead. And the glorified body that never grows old. But it’s hard to put up with life.

How do you regard the development of your theater career?

There have been several periods in what I’ve written. There was the period of The Bald Soprano, in which I shattered the language joyfully. That gave me a feeling of enormous freedom, I could do whatever I wanted with words. Through the middle period, Exit the King, there was hope, there was still God. But later, with time, the breakage of language grew heavier, it became tragic. That’s what we see in my last play, Journeys among the Dead, where there are a lot of ghosts, dead people with whom I speak. In the end, the theatrical game disappears and there is a return to a certain metaphysics. Perhaps with God, perhaps without God, I myself don’t know.

Do you feel that your plays became more and more oriented toward the spiritual?

The Bald Soprano is a spiritual play. Because it is my wonder before the world. In my first play I am amazed by the fact that there are people who exist, who speak, and I don’t understand what they’re saying, I don’t know. In the second play, The Lesson, there is a play on words with death at the end. In The Chairs, it’s metaphysics—there was that mixture of metaphysics and moral ideology. All the time there was this mixture, and the critics didn’t understand. In Exit the King, you have an end that was inspired by the Tibetan dialogue of the dead. At the end the king dies, he loves life, he doesn’t want to die. Then comes resignation, and after that, a spiritual guide who is the queen leads him toward the hereafter, according to the Tibetan rite. “Don’t touch the flower, let your saber drop from your hand, do not fear the old woman who will ask you” I don’t know what. Go up, go up, go up. In the Tibetan rite of death, women surround the dying man or even the recently dead, and they tell him, “Rise, rise, rise,” so that he doesn’t fall into the lower regions, the infernal regions. So the king’s end was inspired by that.

Has the audience become increasingly open to your theater?

At first, they were for me. There were the critics at Le Figaro who were opposed, the latecomers, the imbeciles. And then the young critics were for me, but they were Marxists. So when they understood that I was not a Marxist—I said so, I shouted it—at that point they turned away from me. And the backward critics who had attacked me, they said, “He’s not a leftist, so he’s one of us!” At the start they had said, “Dirty theater, bad theater, detestable theater”; now they said, “Good theater, admirable theater, Exit the King is like Shakespeare,” and other foolishness. Now there’s a return toward me of those who were and are no longer Marxist.

Does it seem that audiences are less confused by your work than they used to be?

With The Bald Soprano, which for me was a tragedy of language, they did not understand. With other plays they understood, but poorly. They understood politically. At first, they were very favorable toward Rhinoceros, because they said, “Now there’s a fine criticism of Nazism.” I had considerable success in Germany. Later, when (Jean-Louis) Barrault’s theater did a revival of Rhinoceros some years ago, it became suspect again, because the people of the left who had said that it’s a criticism of Nazism said, “But what if it’s a criticism of us?” Because it is an antitotalitarian criticism.

So people insisted on being very simplistic about it.

You know, Rhinoceros was a great success the world over. It was played in Spain during Franco’s time, because they said the rhinoceroses are the communists. It was played to great success in Argentina. Perón had fallen and they said it’s an anti-Peronist play. The play was able to be performed in the countries of the Eastern bloc, because they said it is an anti-Nazi play. In Germany they said it’s an anti-Nazi play and that was true, they felt it. But the play was performed in England. At the time, England was a tranquil country—it is no longer a tranquil country. I said to my producer, “The English will have a hard time understanding this play because there was no civil war in England.” In France there were Nazis and patriots, there was the Dreyfus case, with the Dreyfusard and the anti-Dreyfusard. So my producer told me, “Listen, I managed to get you Laurence Olivier as the leading actor, I managed to get you a great director,” which was Orson Welles, “I got you a great theater. Excuse me if I couldn’t get you the civil war in England.”

It seems that everyone wanted only to see their own story in it.

I had asked some young people who hadn’t known Nazism and who hadn’t known communism, the Austrians for example. The theater there was more than full, many many people came in Vienna, and I asked, “Here it is, this is a play in my antitotalitarian spirit. What do you understand now, what is it for you?” And they said, “But it’s clear, for us it is an anticonformist play,” against conformism. So, the play continues to exist.

Has the writing changed much for you over the years?

Oh, I think my plays are very different from each other. Perhaps I boast, but my plays, most of which have not been inspired by any other play, always change, it’s always something else. I went to England recently with my play Journeys among the Dead, at the Riverside Theatre, and the English were very surprised. Apart from nonprofessional companies, my plays had not been performed in England in a long time, because I was against Brecht. The public came en masse; the first nights were full. Then after, the other nights were empty. Because they thought they were going to find an Ionesco who would have made them laugh, an Ionesco like that of The Bald Soprano, for example. I came on at the end and explained my new play to them. So they came back to the theater. But except for the Sunday Times and the Observer, the reviews were bad. They didn’t recognize me anymore.

What about the act itself of writing? Your earliest plays are often dated at the end by the month they were written. That means you wrote it entirely in a month?

Yes. Three weeks or a month.

Did you have to do several drafts?

No. They came out very quickly. A few tiny details I changed, but I wrote them like that. Then I read them over. And when I had a secretary, I dictated to her at the machine. I hardly ever change it.

You’ve always worked like that?

Always.

Even the longer plays?

Even the longer plays, I never change them.

So what brings you to the point of writing? Do you prepare much, do you take notes?

No. I think about a dream, or else I sit down and wait for the characters to speak. And when I’ve heard an exchange of replies between two characters, then I continue.

Do you sense from the start that it will be one act or two or three acts, do you feel the scope of it?

Yes, more or less. I have no preliminary idea when I write, but as I write my imagination completes it. So the second half or more of the play takes shape in my head. Then I know how I’m going to end it. Though I must say that spontaneous creation does not exclude the pursuit and consciousness of style.

Have you ever been tempted to act in one of your plays?

I acted in a film, La vase (The Mire). I was the only character.

Do you work much with the directors of your plays?

Usually when it’s in Paris I work with my directors. The play is developed with the director, by way of squabbling. I take the play away, I give it back again, I take it away, and so on. Especially with Jean-Marie Serreau it happened like that, and with Sylvain Dhomme as well, with The Chairs. I hate when they ignore my stage directions. But when I do the play myself, be it Exit the King or Victims of Duty, which I like a lot, then I myself don’t respect my own stage directions.

Have you learned certain things now and then from the actors?

I have never written for actors. And you must pardon my pride but actors have not affected my plays. The actors are characters that come out of my mind and who must conform to what I have seen in my mind.

I have heard that you travel a lot.

Yes, more and more. California, the United States, the East Coast, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, China, Taiwan, Japan, Senegal, and a lot to Israel. Because I adore Israel. And perhaps sometimes I’ve been such an adept of Israel that now, when I see Arafat, the leader of the Palestinians, now I wonder if I shouldn’t have been a bit more balanced. Because he is unhappy, his people are being killed. But I did not want the Jews to be killed. Because if we hadn’t supported them they would have been destroyed by forty Arab countries. So it was necessary to be on their side, and now it’s necessary to think of the others too, a bit. But I do not understand this rage that exists in Lebanon, in Syria, in Iran, in Iraq, in Thailand, in Vietnam, in the entire world. When I think that it goes back not a hundred years but a thousand years, and not a thousand but ten thousand years, and that it has always been like this, I am absolutely terrified. I tell myself, this world is hell, but hell has no end! Everyone is killing each other. Jesus said, “Love one another,” and it’s as if he had said, “Kill one another.”

Are you superstitious?

Yes, a lot. I believe, for example, that in my last play I mistreated some dead people, some ghosts. My father, who is dead, my step-mother, my grandmother. And I believe that some rather terrible things happened to me because of that. I have other reasons to believe in the immediate unreality because those dead people, in my opinion, are there for some time, and at the end of several centuries they go away. I’ve had strange dreams. For example, I was in England at a friend’s house. I slept in a room there and at night I dreamed that I was surrounded by doctors with white blouses who told me, “We’re going to operate on your brain. It’s not fun, but it’ll be all right, it’ll pass.” And then the doctors leave, only one remains, and I say to him, “Tell me the truth, doctor. I have a brain tumor, don’t I? It’s incurable, and that’s why you don’t want to operate on me anymore?” And he tells me, “Yes, go back home to the country.” The country meaning a friend’s house there. So I woke up, it was dawn, and I walked about from one place to another to see if I knew my direction. Because I had been told that in many cases, those who have a malignant brain tumor lose their sense of direction. My wife wakes up and says to me, “But what’s wrong with you? You’re crazy. Why are you running around the house like that?” I tell her my dream and she says, “It’s nothing, just a story.” Morning comes, we go to breakfast in the dining room. My daughter slept in the room next to us; she arrives and says, “Oh, Papa, you snored last night, a lot.” I tell my daughter, “No, that’s not true, I wasn’t snoring.” Our hostess is frightened, and she says, “Yes, yes, my little girl, it’s your father who was snoring.” All right. My daughter goes out to play, and our hostess says, “Excuse me, it’s not you who was snoring. It’s my grandfather. My grandfather died eight years ago; it’s the anniversary today. Each year on his anniversary we hear his death-rattle.” So I say to our friend who was putting us up, “I know what he died from, your grandfather. He died from a malignant brain tumor. They wanted to operate; as it was incurable they sent him home.” “How do you know?” “I dreamed it.” But I’ve had a lot of other experiences.

There is also a prophetic aspect to dreams.

Yes, the night before my mother’s death—I’m in the process of writing about her death at the moment—that night I saw her amid flames. I wanted to pull her away; I wasn’t able to. The next day she was dead, from brain stroke. And then I’ve had premonitions. During the war I went to Bucharest one year to arrange my military situation. One night I wake up, I say, “Earthquake!” My wife wakes up, completely terrified. There was no earthquake, there wasn’t anything. So we go back to sleep. The next night I wake up. “Earthquake!” My wife says, “But you’re crazy.” And then she feels that everything’s moving. It was true.

What else do you know of ghosts?

There are ghosts in Brittany, but very few. There were a lot in my childhood, because I grew up near Brittany, in the Mayenne region exactly. There were ghosts. There aren’t any more now. They’ve all taken refuge in England.

How do you know?