Edmond Jabès

Portions of this interview were first published in the Los Angeles Times (December 1, 1982) and the International Herald Tribune (July 21, 1983); the entire text appeared in Conjunctions (New York) 9 (1986), and later in Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (Iowa, 1991), now out of print.

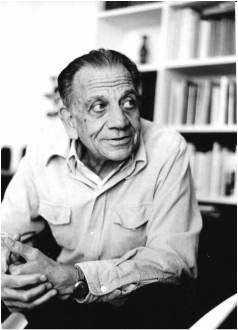

It is difficult to imagine the spoken writer behind the aphoristic intensity of his books. Edmond Jabès (1912-1991) rarely granted interviews, preferring when he did to treat them like another text. Thus, he would pay special attention that it not lapse into a routine repetition of previous questions.

Jabès encouraged an informal yet respectful atmosphere. Hands animating the persistent figures of his thought, he demonstrated how thoroughly he lived his books; practically each statement sparked another observation, another analogy, so unrelenting was his own questioning.

Born in 1912 in Cairo, he grew up in a non-religious Jewish family which had lived there for generations. Given his French education, he began publishing his first books of poetry in Egypt and France in the 1930s. Though he saw Nasser’s later rise to power as a necessary response to English colonialism, he knew that as a Jew it meant he could not long remain there. Jabès was forced to leave in 1957, and with his wife and two daughters settled in Paris. Two years later, his collected books of poetry, Je bâtis ma demeure (I Build My Dwelling), was published by Gallimard.

But the break with Egypt, and the condition of exile, began to work in him. In 1963 the first volume of The Book of Questions appeared, followed in each succeeding year by what was originally felt to be a trilogy, with The Book of Yukel and Return to the Book. Within a decade of the first, the rest of the seven volumes appeared, first Yaël and Elya, then Aely, and finally the last, whose real title is simply a small red dot, bearing the subtitle El, or The Last Book.

Through the last half of the 1970s, the three volumes of The Book of Resemblances appeared: The Book of Resemblances, Intimations The Desert, The Ineffaceable The Unperceived. They completed what Jabès realized to be a ten-volume book, which from the start stymied critics as unclassifiable. In the 1980s these were followed by four books that came to be grouped as Le Livre des Limites. All of Jabès’s work proceeds with a poet’s sensibility, written in prose, where the primary building block is the aphorism, and where a play on words may unlock a long series of reflections. Hundreds of essays have been devoted to his work.

For decades Jabès and his wife Arlette lived on a short street near the edge of the Latin Quarter, a block away from the popular market street, the rue Mouffetard. In their modest apartment, the walls were lined with paintings by friends. The following interview took place over two afternoons in late September 1982. On the bookshelves behind Jabès stood the leatherbound volumes of the Talmud given to him by his father; they were among the only books he was able to take out of Egypt.

How do you, as author of The Book of Questions, feel about being asked questions yourself, as in interviews?

I am always ill at ease in regard to someone who asks me questions because I have the tendency to answer with questions. Interviews trouble me because I have the impression of never really speaking in these conditions. I have the feeling of pleasing someone who poses questions to me by giving him certain responses that for me always remain very superficial. But, the interview is both disquieting and fascinating, in that you are prisoner to the other’s question. You yourself cannot formulate your own responses to things that may seem perhaps more important. And it’s a risk for the writer because he doesn’t know where it’s going to lead him, in fact he never knows exactly what he would like to say. But I think he must play this game. Personally, I don’t believe there are things the writer is privilege to in his books, not in mine. As I accept all readings, it causes me to accept all questions as long as they have their reality for the one who poses them, that they are questions he poses himself in his reading of the text. But anything I can say doesn’t involve the responsibility of my books; you have to read them, it’s they that speak. And reading is something from deep inside, there’s a complicity between the reader and the book.

It was the poet Max Jacob who taught you essentially how to find your own voice. How did your encounter with him come about?

Meeting Max Jacob was of major importance for me. Not only did he teach me how to write, but he was really the most extraordinary guide. At that time I was living in Egypt, and all this poetry that was considered very modern wasn’t known at all there. I was very taken with Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Rimbaud. Then all of a sudden I fell upon a book by Max Jacob that completely fascinated me by the freedom, the irony, where the plays on words appeared in almost every phrase. For me, it was an amazing liberation. Then, I began to examine it and to imitate it in my writings. So I wrote to Max Jacob, I was nineteen; he replied very kindly. I published some texts in Egypt that were very close to Max Jacob’s poems, and then I met him in Paris in 1935. I’d just gotten married and we came to Paris for two months. I had informed Max Jacob of my arrival, he expected me. I went to see him right away. There, I arrived with a big manuscript, a hundred, a hundred and fifty pages, that took some two years to write. He received me with his great kindness, he asked about me, my life, about my wife too. Then he looked at the manuscript, and said, “Yes, I like this phrase, this one too.” He read a poem. “Yes, there it seems more like you,” etcetera. “But, if you like, we’ll meet again tomorrow morning and we’ll talk.” When I arrived the next day, I was very pleased, thinking he liked this manuscript. Then, after a moment, he looked me in the eyes, to warn me, like he was going to do harm. And he said, “All right now, I’ve got a lot of things to say to you, but so that this manuscript doesn’t get in our way, I’m going to tear it up.” He took it and threw it in his wastebasket. For me, obviously, it was a shock, and thereupon he began to speak to me about what poetry was. He explained that it’s not so simple, that the search for a harmony was extremely slow and long, that one had to mature, that this wasn’t mature, it was him. That he had done his time, I couldn’t imitate him. He did it to force me to go more directly my own way, but also to defend himself. Because Max never welcomed being imitated. He knew very well that to be imitated is to be betrayed, I understood that much later. There are some writings that are imitable, and others that aren’t. The writings that are, if you manage to imitate them, you freeze them. Because there are tics to the manner of writing. Well, if you imagine this multiplied to many many cases, when you get to the original it’s unbearable. You feel you’ve read it all. There are a lot of contemporary writers like that, who are interesting in themselves, but whom we practically end up not reading anymore due to the fact that they’ve had lots of imitators. Not just as disciples of their thought, but of their writing.

But you too seem to have such imitators.

No, I don’t think one can imitate my writing because it works along several registers. There’s the aphorism that’s very condensed, the spacious writing, the compact writing, and all that in the most classic of forms. There’s no game about the writing. Writing is imitable when you can grab hold of the trick. There, there is no trick. There is a total limpidity, but it’s along various registers. And this too was Max’s lesson, because we corresponded after, from 1935 to 1940, until the war, and each time I sent him a text he’d say, “No, it’s not you.” Or he’d say, “It’s too lyrical. You should think of the classics.” I’d do it more condensed, he’d say, “No, it doesn’t breathe.” It really wasn’t until much later that I understood that both were valid. That all writing is that, real writing. There are things that must be said with a deep breath, so one can go into a great lyricism, and then things that cannot be said except in the most concise manner. Which is for me where the aphorism comes in, where everything is said in one phrase. But sometimes it’s developed elsewhere. The Book of Questions shows all that physically. Not only within the book, but from book to book. Because if in the first there’s a great lyricism, in the last ones it gets more and more condensed. Another of Max’s lessons was that he saved you a tremendous amount of time, because when he judged a text, he didn’t simply judge it as a text. He saw where it was going to lead you. He’d say, “Now, if you continue along this path, in two years you’ll be doing Apollinaire.” Or else, “You’ll be doing Mallarmé.” So, he put his finger on it. Above all when he’d say to me, “Now you can read Mallarmé.” Huh, I can read Mallarmé? I’ve been reading Mallarmé for a long time. “No, after your text, you have understood Mallarmé.” That is, “You have made an approach of Mallarmé through you.” Because what’s most important is when the author you like becomes a pretext for you, for the questioning of yourself. It’s the way we take in a book that’s important. We can only speak about it by way of ourselves. Your reading of the writer isn’t mine. And yet both are true and both are false.

But there’s a difference between the reader who is just a reader and the one who is also a writer.

Yes, exactly. But every true reader is a writer in force. A true reader is someone who remakes the other’s book. Besides, it’s the movement itself of the book. When you open a book, first of all, it’s a harsh act, because you break it. You open it up, to get out what’s inside. You begin your reading with the first page. You read the first page, you think you’ve retained it all. When you turn the page, what remains of the first, in the second? One or two phrases, an emotion at the moment of an encounter. You read the second page, go on to the third; of the second that you have nonetheless read completely, few things remain. All the rest gets erased. And gradually like that until the end. At the end, the book that you’ve enjoyed, that you’ve read with the greatest attention, becomes a book that’s fragmented by you, by the important pieces of your reading. It’s with that, that you will make your own book. And the author is always surprised when they cite a phrase of his when there were other phrases right beside it that perhaps seemed more important to him. For example, in my own experience, in the last book of The Book of Resemblances there are one or two phrases that were extremely important for me, phrases about myself, that revealed a lot of things. At least I thought so, that they were going to stop there and say, “Ah, look at this, here.” Well, even my closest friends didn’t see these phrases. What does that say? That says you can’t, you, transmit something through the book. It is blank each time. You can’t say, on a certain page, “Here it is,” because the reader doesn’t understand. Finally, it’s that all books work or they don’t. And when it does, it works according to the reading that you have given it. Of my books there have been the most contradictory readings.

According to the critics?

With critics it’s different. The critics try to situate these books, to show their rapport, what they’ve been. The reading of a man who’s very informed, especially who wants to speak about a book, often does not have the innocence of the reader who reads only for himself, who says, “Others’ opinions don’t interest me, the author’s opinion even less, it’s my opinion that counts.” There have been completely amazing readings in that respect. For example, a young employee of a bookstore who didn’t read any books. A young Jew, very religious, who said his prayers four times a day. He read nothing besides his prayers. One day, he was in the bookstore, there were no customers; the manager liked my books a lot, so she said to him, “Listen, there’s nothing to do, why don’t you read The Book of Questions?” And he said, “No, that doesn’t interest me.” She insisted he go look at the book, the first one. He began to read it, then he closed it, put it in his briefcase and was going to buy it. She said, “But I didn’t say that for you to buy it. I told you simply to read it.” He said, “No, no, I want it.” To prove what? This young man wrote a letter, by way of this friend, to tell me that for him his prayers are incomplete now if he doesn’t read each time a passage from The Book of Questions. This friend was so surprised and even touched by this, that she went to give him the second and third, which form a trilogy, as a gift. He refused them. He said, “No, that doesn’t interest me. This is the book, that’s all.” Well, what would you say to someone like that? You can’t tell him, “Your reading is wrong. Me, I’m not practicing, I’m not a believer.” Approaches to a book assumed in such a manner, they’re astonishing.

Why do you think it’s happened like that?

Because, see, it’s a book of putting into question. A lot of young people have been very interested in these books because they don’t feel at ease with themselves. So, there’s an amazing questioning that has touched them, since to question is to put oneself in question each time. I permit myself to say this because it’s above all young people who have taken these books in hand, in a surprising way, whether in France or elsewhere. And who assume them entirely, it’s their book, they live with it.

But how do these reactions affect you? How do they affect the writing?

Each time it raises questions for me, because it’s a reading I wasn’t expecting. At the start, when they tried to read it comparing these books to those of the Jewish tradition, for example, that annoyed me, because that wasn’t at all my point of view. But after, I told myself at heart, if I use the word “God” in all the books, without believing in it, even so there is a fascination. The word “Jew” is in all the books, it’s something that haunts them, something that’s important. So, it has made me think. At any rate, what I’ve tried to do with these books is to preserve the opening in preserving the question. And the question is the opening itself. In regard to Jewish thought, the question is very very important. There’s a bringing together that’s done in a natural manner.

How did you start writing?

It comes from way back, I believe. Moreover, in The Book of Questions there was a page at the beginning where I say, “When, as a child, I wrote my name for the first time, I knew I was beginning a book.” And this phrase responded to something that was very true for me, very profound, which I must have experienced quite young. But I had it confirmed by one of my granddaughters, it’s amazing. She was five at the time, she’d just learned how to write, and the first thing she learned was to write her name. So, she came in one day with a big sheet of white paper, where she’d written on top, Kareen, and in a very cool manner, she said, “I’m leaving you my book.” I was impressed, because I said to myself, It’s true, the child, when he writes one phrase, thinks he’s writing a book. At the start, when he doesn’t know how to write, he puts three l’s or two m’s or whatever, he thinks he’s mastered it all. And the disappointment for the child comes when he has really learned how to spell. Like everyone, he has to learn how to write the words, not the word he invented, the word that represented the whole world for him. They’ve reduced the word to what it is. And when a kid starts to write, the first thing he wants to write is his name. Naming is extremely important, I deeply believe. As soon as he has written his name, he’s said it all. Kareen, that’s me. It’s over. What else would you have her say besides Kareen? That’s the whole book. Because the book is only a name, nothing else. It’s the approach of a name. But I’ve made a digression. In fact, I started to write quite young, at the age of nine, things that are without interest. I published a book of poems at the age of seventeen, in France moreover, which had in very official, very academic circles a lot of success. It was called Les illusions sentimentales, very Baudelairean. It was a period when I came to school wearing an ascot sometimes. And it’s funny, this book got me entry into the literary salons of the time, like that of Madame Rachilde, where there were senators, deputies, academicians, who sent me letters. I was read at the Comédie Française, by one of the great actors, and it’s a detestable book. Then, I wrote other books in the same vein, a false romanticism, and from there some time later I discovered Max Jacob. That was an introduction into a certain modernity, because I didn’t see at the time the modernity of Mallarmé or Baudelaire. Then, after having made this necessary transition, there was a return to these great writers, but after having played the game of a certain modernity. Having discovered Max Jacob, I published a book of poems in Cairo called Les pieds en l’air (Feet in the Air). The titles of the poems were on the bottom, and it was a whole play with puns and such, very close to Max Jacob. After, I wrote a book of essays, precisely on this work. All that was disowned, obviously. Then I wrote this manuscript that Max tore up, and from there on I followed Max’s lessons. I think really the first book where there is a writing that’s already mine, to a certain extent, is Chansons pour le repas de l’ogre (Songs for the Ogre’s Meal), which were written in 1942-43.

And were you writing other texts at the same time you wrote the books of poetry in the 1940s and 1950s?

Until about 1951 I only wrote the poems you find in Je bâtis ma demeure. But I wrote a number of plays. They were performed on the radio. When I came to France, I had been in a very difficult situation materially, and one day I received a letter from the radio which said, “We are in the process of trying to bring writers to the theater. If you have a play to propose, send it to us.” I said, “Why not?” So, I took out one of five plays, that I cut a little or whatever, since it was ten thousand francs they were offering. And it was accepted, it played on the radio several times, here, in Canada, in francophone countries. But I don’t keep any of that.

Did the theater work influence your books?

No, it was entirely different. Now, with the distance, if I could find an example, it’s like the theater of Pinter. A bit harsh like that. Very stark, the situations. Because theater has always fascinated me. I was always performing, at the age of fifteen I had a theater troupe. Every two weeks I put on a play with friends, and half the times it was a play I wrote myself, little comedies, one act. But theater wasn’t really my path. When I came to Paris, as Je bâtis ma demeure was going to come out with Gallimard, I showed the plays to a friend, one of the big theater critics. He found them very bad, saying they weren’t worth anything. I thought at the time it was very courageous of him to say that with such frankness. It reminded me a little of the way Max acted with me, I trusted him immediately. I completely abandoned theater, and little by little The Book of Questions was born.

What has been the value of memory in your own life and work? What has it taught you? How far back do you remember?

It’s very difficult to say which is the first recollection, especially because I don’t believe so much in the remembrance. I believe in memory and not the remembrance. Memory is something that is older than us finally, while remembrances are moments of our life we ourselves have been privilege to, which we have given a certain duration that perhaps they didn’t deserve. There’s an old recollection, that I hadn’t remembered, but which I discovered in a poem from Chansons pour le repas de l’ogre. There was a fairly ambiguous phrase but very poetic, full of images, and I realized that I hadn’t understood it. Because in fact, everything I’ve ever written comes out of something lived. There’s never been any invention on my part, there’s something lived behind it. So, I questioned that phrase, not in a logical manner, but I wondered how these images could have come up, as they were so unusual. Suddenly I remembered a very strong emotion I’d had, of fright, one night. I must have been four or five, and I was coming back home with the person who accompanied me. In the neighbor’s garden was a huge wolf-dog, who knew me well, and he stuck his snout out through the gate. I wasn’t used to coming back in so late, and I saw him that night with his sparkling eyes. So, it became that phrase, something that followed me with these lynx’s eyes. That’s what memories are like. On the other hand, I think what deeply affected me was the death of my sister. It was horrible, and from that moment on I felt myself to be another, I changed.

Then do those two selves come together again in your writing?

Certainly. I don’t think we’re made of just one piece. We’re sometimes one, sometimes the other. And happy memories are sometimes as strong as sad ones. We’re caught between the two, and surely childhood memories that were happy but turned sad due to the war are in the first poems of Chansons pour le repas de l’ogre. That collection was written during the war, and it’s very strange that they’re songs. It’s because at the moment when the world was going up in smoke, when we were being menaced all the time, there is like a return to childhood, as if childhood could protect us from death. And so, there were these songs, that are quite surprising in regard to what I was writing before.

And you only kept the writings that went along that path?

No. Because in Je bâtis ma demeure there were other poems that are very different from the songs. There’s work that was close to surrealism for me. And then, other work close to René Char’s poetry at that time; a book is dedicated to him. It’s not at all René Char, but his thinking, his aphoristic form, was important for me then. In my development there’s Char, the surrealist poets, Eluard, in the first texts, which were more imagistic. But at the same time, there was Egypt, and a reflection on language that wasn’t elsewhere, which was utterly myself perhaps.

The vocabulary in Je bâtis ma demeure is greater than in The Book of Questions.

Yes, but it is perhaps easier to write with a lot of images than to write in a way that’s very plain. Because if you speak with many images, it easily seduces sometimes, though obviously not always. Whereas you can’t be fooled with a clear limpid writing. Right away you hear if it’s bad there.

But is that one of the things you were trying to do in The Book of Questions, to strip down the writing?

No. The poem full of images has always frightened me, because that profusion causes one to be practically unconscious of them, thus devoid of any logic. I wanted to understand, it was a way for me to shatter the image and at the same time to rid myself of it. Gradually through the work I was able to get rid of the image by questioning it. Thus the aphorisms, especially those on the text. And that’s already one of the experiences of the desert, but which I didn’t sense at the time, because I was still thinking of writing poems full of images, which is the opposite of the experience of the desert. But the desert was already working around in there, unsettling things, like a subversion.

Now and then you spent time in the desert. Why did you go?

The desert was a necessity, that touched on a lot of things. First of all, in Cairo we were a fairly well-known family, and the European colony was really quite small, in that people frequented each other along social levels. Which means that, say, if we were in Egypt of the same social level, I knew everything about you and you knew everything about me. Well, that was a big burden on me. It wasn’t me inside. And I had always had a great fascination with the desert. Because the desert is at once everything and nothing. So that, when you are between sky and sand, you are truly in infinity. Outside of time. Time doesn’t count. Not only does time not count, but it’s the spoken word itself that loses its necessity. And that was fundamental for me, who was seeking—as with the questioning of a poem—a word of truth. Because I’d always tell myself that if with the same word one can practically say the thing and its opposite, in the same manner, with the same force, then what is this word? What is this word that plays with us, and that causes us to enter this game that is almost a metamorphosis? So, where is the truth there? What is the word that in the end can tell the truth, that can tell what we really are? Well, the desert teaches you first of all to get rid of everything that’s useless. And in fact, if we speak, it’s because we speak of things that are very close, very deep for us, and at the same time we speak of all the futility with which we live. This stream of words crowns the act of speaking. The desert teaches you to forsake that. And it’s very difficult, you know. So, I went there to depersonalize myself. That is, to no longer be who I was in appearance to others in Cairo.

How long did you go there for each time?

I went for three or four days, all alone. I could have stayed longer, but sometimes I couldn’t stand it anymore. It’s extremely difficult. And I’ll tell you why. For the Arab nomad who lives in the desert, what counts is the space. That’s his domain, his country; those are his limits, they’re unlimited, he needs that. The desert for him is life almost, because he’s born in this desert, which has made him in its image. So, they’re close to each other. While for the rest of us, who are formed by the city, by the culture and such, the desert is something that suddenly presents the end of all that. That is, that no great culture, no great thought, subsists in the desert. In that infinity it becomes almost derisory. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t impel you to meditation, doesn’t push you very far within yourself, but you’re not going to just start reciting a poem by Victor Hugo in the desert, it’s not possible. You understand the desert is much more the listening than anything else. Now, in the life we lead, listening practically doesn’t exist. People speak, but they don’t listen to each other. Well, the desert is listening pushed to the extreme. And to which you can’t even respond with words. You’re obliged to submit. Because when you arrive, at first there’s an amazing silence that completely cuts you off from the noise of the city. So, at the beginning, it’s very beautiful. But after a certain time, the silence becomes heavier and heavier, because it’s a silence that has cut you off from speech. You don’t even need to speak if there are two of you, because there’s nothing to be done. You tell someone even the minimum, “I’m thirsty, I need a glass of water,” you can’t say it. There is no glass of water, there is no thirst, there’s nothing. You are there with yourself. So, you don’t speak anymore except to say one or two phrases, that are the most profound and at the same time nothing in themselves. For example, “it’s beautiful,” and that’s all. Well, “it’s beautiful” doesn’t mean anything, understand. You can’t develop it. If people like us can’t bear the desert, it’s precisely because this silence is too strong. And after three or four days, you want to hear something that’s not this nothing. Anything, that says, “I’m walking, I’m living, I’m dying, I’m singing.” Which makes me think of people in the Middle Ages locked up in towers and who suddenly broke out screaming; it wasn’t to call for help, it was to hear their own voice, to see that they were alive, to say, “I’m still alive.” Well, the desert is a language of death. Because even if there are two of you, you speak in another way. There’s a way of speaking to children, for example. There’s a way of speaking to those who are going to die. It’s not the voice we use when we’d go get a pack of cigarettes. It’s another voice. And that I had experienced precisely at the age of twelve, as I was saying, when my sister died practically in my arms. I spoke to her but my voice was another. It was a voice that followed the measure of hers, beyond measure, a smile which could only say the essential, that is, the last words one says before dying. In a certain way, we had reached the last word.

But what did you see in yourself, for example, when you returned from the desert each time?

Well, it did me a lot of good, because I had the feeling of having saved something that had been fatally lost. I don’t know what it was, but it was something that had enriched me. Because it had lifted off of me all that was too much. In the work of writing, one recognizes it. Because what is writing? In writing one lifts away everything to get to a word that’s more profound. Writing is also a pushing inside, and that’s what the desert brought me. So, I really felt quite enriched and more able to put up with the rest.

How did you go back to writing after the desert?

Yes, that too was something that disturbed me enormously, because I said to myself, How, living in Egypt, with this experience of the desert, did I manage to write Western poems, nearly surrealist? Thus, the opposite of what I was living. I think it’s because it takes a lot of time with writing to make use of what a man has lived. You cannot write, at that very instant, what you are living. You live something very intense, you can neither speak nor write about it. It’s only a long long time after, that it comes out in the writing.

And yet between those two points, it’s not really memory that connects them.

No, precisely. Because we ourselves are like a very sensitive plate, and we don’t know what marks us. In fact, everything marks us in a way. And what marks us most deeply, we cannot know at first. But we can know later, sometimes long after, because precisely this thing that has marked us the most has been at work in us, more than other things. And then suddenly, it appears in another form. Writing alone is able to preserve all the moments lived, to restore them to us, with a memory that will recapture it all, and you’ll be surprised to see how it all comes out again. Because it’s based on what has touched us in our lives. Which the spoken word cannot produce, because it’s sometimes inexpressible. In Egypt my poems, which were read in France, meant for me that I was entering into the family of French literature. But that’s not the desert, right. And I had only dreamed of one thing, that is to be published, to be integrated into French literature. So, for me that was more important than this experience of the desert which I felt but could not manage to define. I’ve never spoken about it to anyone.

Did Arab culture enter into your education?

Not right away. Because at first, of course, there were the French schools. French philosophers, French writers, the history of France, and so on. But fairly quickly I became very interested in the great writings that are the masterpieces of these countries. Unfortunately in translation. I read Arabic, but still it was an effort, and I preferred to read them in translation. So, I had a certain rapport with Arab literature and philosophy, and then I realized that in the Muslim tradition, with the Sufis for example, there were completely amazing things, as in the questioning of language. At the same time, I was also beginning to read the great Jewish mystics, who wrote in Hebrew and Arabic. All that is a part of the East, which is a world quite apart. Even the West, which penetrated quite considerably, didn’t deeply mark the East, didn’t shake things up. For example, in the time of Romanticism, they created an East of fantasies, the men with their harems, the sad women, and so on. It’s not that at all. The West has lived on this image of the East which is completely false. And the East accepted the West, because the West brought it a philosophy, a way of thinking that was entirely new. But which didn’t deeply affect it. There is a wisdom in the East that the West doesn’t know. The wisdom of its peasants has nothing to do with the wisdom of the French peasant who is crafty, who counts his pennies. The others, it’s an extraordinary wisdom, one would say they’ve traversed the centuries. And it’s the landscape too that leads to that. These people have a thinking that’s extremely deep but doesn’t appear to be. The intellectuals have certainly been marked a lot, but they’ve poorly digested the West. In fact, the Westerners, the European intellectuals, lived on Western culture much more than Arab culture there. They lived that Arab wisdom and culture, but without perceiving it, like a background.

What for you is meant by “the book”? Are there particular writers or books that you think of when you use the term?

Perhaps I should speak about precisely this book, The Book of Questions. Because it’s then, after the break with Egypt and my arrival in France, that the desert finally imposed itself on my books. How did I have the idea of the book? I really had no idea. We had spoken a lot about Mallarmé, precisely concerning his idea of the book. But it’s an idea that had never really attracted me, because I had always thought that a book which presents itself as the book, where everything we could put there would be inside it, all knowledge, it’s not eternal. It would be a very ephemeral book, because we’re not made to talk or write for eternity, but for the moment. And it’s the accumulation of moments that makes continuity. That’s part of what I wanted to show in these books, in that they work in this way: the first is in the second, that is the second continues the first and at the same time takes its place, and the third one too, and so on to the end. So that it obliges you each time to do a double reading, a reading forward and a reading backward. And for me, that is life itself. That is the book which could have a certain duration. As I think a book is made only by what’s missing in the book. You have to leave the reader room to enter. Not only room to enter, but room to add his thought there. If you close him in by telling everything, it’s all over, you suffocate, you die. And repetition is the most constructive thing there is, because one never repeats oneself. Even if you say the same thing twice, it’s not the same thing. Because there is a second that has passed, and the second repetition is linked to this new second. There has been a second more lived, which will change things. Take the case of two people who love each other, and they say to each other, often, “I love you.” Why? Once is enough. They repeat themselves because they know very well that what they say today is not exactly, even if they are the same words, what was said yesterday. There has been one more day that has caused us to change each time, and everything changes with us. And that everything carries the burden of this change. So, it’s this book that haunted me, this book then that passed for being ephemeral and which confronted the desert’s eternity, this duration of the nothing. Because it was like a word that wanted to go further than it could go, in a way that it could be heard by the surrounding infinity. A second that was making its entry into eternity. Not to assume eternity, but to allow it to be, because eternity is made of every second. There where the instant was continually confronted by eternity, exactly as the thought found itself constantly confronted by the unthought which obliged it to go further. So, the book had become a real place for me. Then there was also this, that I’d left Egypt because of my Jewish origin. As I said, I was neither practicing nor a believer, I’d always lived in this country which was mine, and one fine day, when I wasn’t prepared for it, I was forced to leave because of being Jewish. So, that posed certain problems for me. I said to myself, We do not escape a certain Jewish condition. At the least expected moment, things explode and, without knowing why, you’re forced to abandon everything and to lead a life of exile, of wandering. Finally, little by little, I realized that the Jew not having had a real homeland for thousands of years, since obliged to leave one place for another each time, what did he do? He made the book his true home, his real territory. And you find in the books of the tradition, in the Kabbalah, in the Talmud too, a questioning of the book, because it’s there that the Jew’s freedom was exercised, it’s in the book. It’s there where he could speak and where he could hear his words. Elsewhere that was refused him. And I found that there was such a similarity between the Jew and the writer, that it struck me in an amazing manner. There’s a text in the tradition that says that the Book, that is the Torah, was given to us in an order that’s not the right one. And that it’s up to us to find the Book’s order again. Well, that’s the writer’s whole task, to find the book’s order. So, when they called Jews the people of the book, it’s true, they are. And little by little I told myself, Me too. Oh, I was at home in France, but it wasn’t my landscape. And for all that, the book was substituted. That is, I too made the book my place, my homeland, as if I could live only in the book. And from there on, I was caught in a movement, as if the book was making and unmaking itself with me inside. So, an entire memory arose, everything that’s marked us after Auschwitz imposed itself by stories that are never told, that are presented just like that, like something that everyone knows, and around which a whole reflection takes place. But a reflection which each time was that of the book, the book questioning the book. They’ve often said these last few years that the writer doesn’t exist, that there’s only the text. So I wonder, first of all, how a text can exist without a writer. But if they’ve said that, it’s because the rapport with a text, when it is very deep, causes the writer to so become his word that he becomes text. That doesn’t mean he’s done away with. He is his word for once. And it’s that word, which is supposed to be the most profound, the word of truth, that was my constant search. In the first trilogy, it’s the story of Sarah and Yukel, who are two lovers that are deported. She’s quite young, she comes back mad and her cries are the cries of her people. He ends up committing suicide, because he knows that he can’t enter Sarah’s madness and that it’s only madness that could have saved him. That lucidity after Auschwitz was untenable. So he kills himself, but also because he reads on the walls, like one read everywhere, “Mort aux Juifs,” and so it’s that simple thing, the drop that made the vase spill over. And that’s something I myself experienced profoundly. I left Egypt, forced to leave, chased out, losing all my things, to come to France which welcomes me. And what do I see the very day of my arrival in Paris, on the walls of the building across from where I was living? “Mort aux Juifs, Jews Go Home.” It shocked me. I said to myself, How is it that no one has the idea to erase it, to say “I don’t accept it?” And so, I picked that up again in the book finally, in a much more dramatic manner for Yukel, who had lived through the deportation, who came out of it with his reason intact, who says, “It’s not possible. One cannot, after that, keep one’s sanity.” Who has the case of Sarah his lover who is mad and raves. It’s this simple graffiti no one takes seriously, but which came at that moment. So, that was a story that was never told, but around which of course all the reflections, questioning of language, death, life, everything. Roughly, historicity. Then, we come to two others, who are Yaël and Elya, in which there is the direct questioning of the word that failed after Auschwitz. Yaël is a woman who lies to the person she lives with, and he thinks he’s done her in because he was seeking a word of truth. It’s here that she lies because Yaël symbolizes the word, our word, our own speech as an individual. And Elya is the silence, the still-born child who symbolizes the silence from which the word emerges. So, Yaël invents a life for this still-born child, she refuses death, but only to be able to continue being a word, to speak. Then, we come to Aely, which is a very difficult book. It’s the eye, the gaze of the law, it’s the one who judges and who has not participated, who doesn’t participate in anything. Who judges everything. And in fact, it is the gaze of the book upon the book, in short, upon everything that the book is. And the last book is the point, the smallest circle, where I thought I’d come to the end, and where I found a reference to the Kabbalah, where it says that God to make himself known revealed himself by a point.

You had already read the Kabbalah by then?

No, no. That’s after. All the references that I made to Judaism, that is to the texts of the Talmud or whatever, are transformed in my work. They hadn’t aimed to simulate it, but it was like a verification for me. All at once, I said, “Okay, now that I’m that far into Judaism, what is this Judaism, let’s look a little closer.” And so, I rediscovered things there that I had written long before, with such precision it was as if they had been dictated to me. But transposed, transformed.

How do you explain this rapport?

I don’t know. It was completely surprising.

At what point did you start reading the Talmud and the Kabbalah?

Well after the first volumes of The Book of Questions. I found things that had come to me as a writer, and not at all as a Jew. I was first of all a writer. And I realized that to be a writer is to be a Jew in a certain way, it’s to live a certain Jewish condition, separated, exiled. And that the problems that are posed to Judaism are posed regularly to the writer, because the Jew had nothing but his book, that he had to force himself to read and to understand. Whence all the commentaries of the book. Whence the obsession with what’s been written. Not just with what’s been written, but with what conceals what’s been written. What must be read. As if there was a book hiding another book from me. And there too I draw a reference to the writer, because I deeply believe that each writer carries a book in him that he will never do. All the books he writes try to approach it. And if he never does this book, it’s because if he managed to, he wouldn’t write anymore. Because this would be the book. And if it’s undoable, it’s because our speech is not definitive. It’s a speech made up of changes. We cannot express ourselves in a total manner, only by small steps.

How is it there’s a book inside? Does not that book also change?

Ah, it changes too. Each time it’s a book that we want to do, and that we carry in us. It’s not a fixed book. It’s an idea of a book, a book that keeps reworking itself, but which is blank, illegible. And we ourselves try to render it legible. It’s that, listening to the book. When we say there’s an order to the book, it’s true. I heard the articulation of the book, exactly like in the desert where you hear before seeing. It’s amazing, because when you put your ear to the sand, you hear some noises, and then an hour later you see something appear. That’s what I called the listening and the speech of the book. There’s a book that speaks to you, but which speaks so low you don’t hear it. You hear odds and ends. And then all that becomes articulated.

How did you proceed with The Book of Questions?

This idea of aphorisms carried the thing along. Then, at times it would develop into something larger. And I’d say, “That goes there, but between that and that, something’s missing.” Exactly like when two people speak, you miss a word. You say, “Please, I understood, but what did you say before? I didn’t hear it.” There’s a gap. And then, all at once, something came, and I felt that it was what I hadn’t heard at that moment. So, it was a perpetual listening, a continual questioning of the text. And it’s an immense movement. Like when you swim in the sea, you submit to the waves, you cannot just swim as you like. You are caught in the water’s movement. There too, I was taken up in the book’s movement. And it’s very curious, when the first book appeared, there was an interest right away, and then those who were interested couldn’t imagine that there would be a second book, and a third. And I had even said to the editor, several times, “It will be a trilogy.” I didn’t know why, I hadn’t a note. When the second book appeared, there wasn’t a disappointment but it wasn’t the impact of the first. When the third appeard, they understood that a loop had been made, and I myself was the most surprised. When you think that The Book of Questions and The Book of Resemblances is ten volumes, that makes twenty years on the same book, practically. On the same questioning, the same listening. Twenty years! If they had told me that at the start, I never would have launched into such an adventure, because it’s not easy to keep up. Each time to arrive at the void, always the beginning. I never conceived of the book as something that had to be done only by me, by my will, by something premeditated. As certain novelists, for example, construct their novels.

Where does the next book come from each time? Is it something interior to the work?

Interior, absolutely. And if I speak of the book that’s inside the book, it’s because each time there was like a book that came out of the book. That which is in parentheses, for example, in italics, is another book that emerged from this book.

What you understand now about these books, did you understand that then?

No, not at all. I was in total darkness. I didn’t understand what I was in the process of doing, I didn’t understand the break. I suffered terribly from it, because I didn’t see where this adventure was going to lead me. Each time I felt myself a little more cut off from French literature, which I was so attached to, that I was losing my filiation with it. That I wouldn’t find again the great writers whom I relied on. And what demonstrated this to me is a correspondence I had with Gabriel Bounoure, who was an extraordinary man, a fantastic essayist quite older than me, and who participated in the creation of these books. Because I was sending him passages I was writing, and he too entered into a questioning, “But why that, why not that,” etcetera. Which shows at what point nothing was fixed in advance.

How did you know you were on the right track?

I felt this development intimately. Something else I realized is that the question, which is fundamental in these books, unfolded in a manner that was almost outside of me. There is a passage where a young disciple asks his master, “If you never give me an answer, how shall I know that you are the master and I the disciple?” And the master responds, “By the order of the questions.” When you live the questions deeply, you cannot pose certain questions before others. It’s as you go along that the questions are posed, until the last one, which remains a question. And all the questions reaping only unsatisfactory answers, to a certain extent, the question continues. If the Talmud is a book without end, it is because the questioning is without end. How does the Talmud proceed? By rigor and by questioning. And so, you find in these books, for example, a question in the first one, which you find again formulated differently in the third. You have to go through two whole books before that question returns, and which will bring a different answer. And if there are all these characters that I call rabbis, their voices, it’s to permit each one to say a thing that is sometimes in contradiction to another. Whence the flow of these characters, who enter and question, question. And they question in time and outside of time. One hears a lot about the récit éclaté, but this is an example for me of what is the true récit éclaté. It’s not about bursting the story itself apart, it’s to burst apart the place, in abolishing it. These imaginary rabbis, how can we situate them in their time, because it’s never said? We see it in the long run by what they say. That is, the oldest say the simplest things, and those who are contemporary say the things that are most developed, most complicated, because they’ve inherited all that. So, they speak in and out of time, and there is no place. There is no time and there is a quotidian. It is a time outside of time within time itself. Whence the importance of the story, because the story is situated. Without fixing a date, we recognize it. It’s given a dimension that it would never have if it were only a story of something just presented in that way. All that, then, makes this sort of permanent rupture, because I don’t believe in continuity. Continuity is made of ruptures, and we ourselves are this rupture. And the rupture is the broken tablets too, at the start. Because if Moses was constrained to break the tablets, it is because the Hebrew people could not accept a Word that came from elsewhere, a Word without origin. He had to break the tablets so that they would understand, so that the human word could enter inside, after the anger. Something human passed through. So that the Hebrew understood, he comprehended it. Otherwise, if it is a word coming from the invisible, from a God, what is it? The break was needed. And it is that break there that has always haunted me, with metaphors of injury and so on. Because I deeply believe that since Auschwitz in general, the word is wounded. And that our speech is different. It’s as if we are speaking with someone who has an injury. We cannot escape it. And if you have an ear that is very attuned to what young people or those who are not so young are able to say to each other today, you hear behind it something that has been deeply affected. And what has been deeply affected is in that speech. The words say the same things obviously, but at the same time they tell their injury, in a certain way. For me it’s entirely evident, I hear it like that. In even the simplest, most ordinary speech, I hear that there is a weakness. There is a weakness. That is why we can no longer put up with moral judgments, things like that. We are fragile beings, very fragile now. And we can no longer speak like before. Because we can only speak with this fragility, and from this fragility. We know that there have been such things accepted that in fact it puts everything in question, even culture. As I said to Marcel Cohen, to the statement by Adorno, the German philosopher, who had said that we cannot write after Auschwitz, I say that we must write. But writing is entirely something else. We cannot write like before.

But how do we read this other writing? How should we read The Book of Questions, are there certain ways?

Listen, I myself don’t know. For me, now, it’s a reading of the whole work. That is, I cannot imagine a reading of these books that would not be of the ten volumes. Because each brings something to the other. The first book could be read by itself quite well, and all the books can, somewhat. But in my opinion, one misses a lot, above all this movement of the book, how it makes itself, and then how it unmakes itself and makes itself again. And each time further. I understand quite well that one may not be able to read the ten, and that only one at a time can be translated. In each one there is the book, the essentials. But I believe they are books that call for the continuity of reading. But this said, how to enter into these books? I don’t know, there are people who have begun by reading small bits. I think that’s a rather good reading, a phrase here, a phrase there. One is not in the book, but that doesn’t matter. One circles around it, at the threshold. And then, if one happens to enter it, to see again from the start how it’s articulated. How one page calls to another, how one question leads to another, how the story more and more gathers pathos. It is very difficult, in speaking of these books, to try to circumscribe them. One cannot. Perhaps that is the reading, to grasp it by fragments, and then with all this baggage to enter inside. And then, to participate more deeply in the book. That’s one of the reasons most true readers end up by assuming these books, that is to make it their story, their book. I know people who have gone off with it into the desert, others into the mountains, that they could only read the book like that. I ask myself, What does it do that it can work for certain people in such a way? That’s not normal for a reader with a book. There are also people who say they can’t read it, who read a lot and who’ve had a hard time reading these books. And there are people who don’t read anything, and all at once say to you, “Ah, there it is.” It’s something else.

Perhaps you’ve found a way where the words are not wounded.

I can’t explain it myself, because with me it works in the same way as them. Each book for me was very very difficult. What allowed me to go to these limits in the end—which are the limits of the book, but also my own limits—was the fact that I was conscious that one does not say it all, one cannot say everything. And that each time, there is still something more to say, still a question. There is still a new adventure. Even when one reaches total effacement. For example, this word has been taken all the way to its end for me now. The book that haunts me at the moment is a book I’ll call Le Livre du Dialogue, where I ask myself the question, Can there be a dialogue, for me, now? And what is this dialogue? What dialogue can I establish? There is always a dialogue, because thought itself is a dialogue. Writing is a monoluge, and at the same time it’s a dialogue. But in regard to another, what else do I still have to say? To one’s questioning, what word shall I be able to formulate, not to respond, but to keep up this dialogue.

Is Le Livre du Dialogue one book?

I don’t know. I’m bringing it along like that, there are passages that come. It is to a certain extent already articulated. The first part is “L’Avant-Dialogue.” Second part, “Carnet,” reflections. Third, “Après le Dialogue,” the dialogue hasn’t taken place. Fourth, “L’Abîme.” Fifth, “Le Dialogue.” I don’t know if they’re the titles that are going to remain, but for me it imposed itself like that. It’s a way of listening.

Does it take up again any things from the previous books?

No. It’s a bit like Le petit livre de la subversion, that’s not part of the series but which is still a book of the same family.

You’ve said that Le petit livre is a sort of key to all the other books, as in the way it speaks of subversion.

Yes, because they’ve spoken a lot about subversion à propos The Book of Questions and The Book of Resemblances. And I wanted to see a little closer what subversion was. I realized that subversion is something that someone else cannot suspect as such. And if there is subversion in The Book of Questions, it’s because we become disturbed unawares. It’s there that subversion works. And that led me to think that the more one is oneself, the more one is subversive in a way, in that the difference stands out. The great subversive books, for example, were not at all written with the aim of being subversive. As in the case of Kafka, not only did he never for a second think of being subversive, but he thought that his books were not modern. He was envious of other books, such as those of Brod. “I don’t know how to write,” he says. “What I’ve written is without interest.” And all at once, they’re revealed to be the most subversive books. His books are disturbing because he was the most profoundly himself, he could write only as Kafka alone could write. They became subversive after.

You have written and are planning other books outside The Book of Questions. What are they?

Some small essays, with aphorisms and such, have been published by Fata Morgana press, with the painter Tapiès. The first book is called Ça suit son cours. There’s a new book, Dans la double dépendance du dit, which is my relation with writing, other writers and their thought. Contemporary writers mostly. A third collection, that I haven’t written, will be about Kafka and the Prophets. As these aren’t essays that try to show what a certain writer is, but rather my relation to the text through him, I would like to show what in Kafka opened certain paths for me, and which perhaps are not in Kafka.

By way of his subversion.

Right, what I experienced as entirely subversive.

Have you seen any particular differences between Jewish and non-Jewish readers of your books?

Not in the reading of the true reader, who, Jewish or not, has really felt these books in a rather strong way. I think a Jew could read these books differently, but not in what he has deep inside. In what he has superficially. That is, he’ll recognize certain anecdotes, rites really, a Jew recognizes them right away. But that’s the exterior aspect. When one reads these books deeply, one perceives that this is a Judaism gone beyond, carried further, toward the universal. And it’s through that, that there is a real encounter. Precisely by being open, by the questioning, by the refusal of everything that is fixed. So, in this sense, readers have felt that deeply, and these levels have been assumed in the same way by non-Jewish as by Jewish readers.

What was the reaction of Jews?

As everything is Jewish finally for Jews, those who were the most sectarian ended up saying that perhaps the book is Jewish. But at first, it was very disputed. There were people who attacked me saying that it had nothing to do with Judaism, that it was a fantastic Judaism, that there was no rupture in Judaism. All right, I never said it was Jewish. I said, “That’s my experience as a Jew, that’s how I have lived a certain Judaism.” I think that Judaism does go through the book, that true Judaism is there. And what’s surprising now is the acceptance of this point of view, which was simply personal. And yet it’s not so surprising, because there are many ways to live this Judaism. There is a religious Judaism, and an atheist Judaism. And we cannot tell the difference between the two. Because never have we seen, in no other religion moreover, the faithful speak with such freedom in their places. As with the Talmud, they accept the Word because it’s the Bible, but at the same time they discuss it, they have to understand it. In other religions, they don’t discuss, it’s faith. While there, no, they must discuss it. Also, it’s very curious, if someone wants to convert, for example, never will a real rabbi ask him at the start if he believes in God. You don’t see that. He’ll say to him, “Why do you want to be Jewish? What madness has come over you that you want to be Jewish?” So, he has to explain himself. And it’s not easy. Because Judaism is something else, it’s an ethic, it’s a way of living this Judaism, of questioning, of being open, of solidarity. Of memory. And that’s something that annoys the Jew when he sees someone converting to Judaism. Because he says, “He cannot have this memory that we have.” And it’s very true. With each event the Jew puts himself in question again, as a Jew, as if he had lived a life five thousand years long. And one wonders why. The French, for example, they fight the war of 1914, they’re not going to think of the Gauls. While for Jews, when anything happens, they remember. There’s an unhappiness, oooh, that goes back five thousand years. They bring out a whole endless history, as if they themselves had lived it. And they do live it each time. They live an entire history with each event. Which is completely amazing.

But that too recalls the writer, with the memory, because each thing . . .

Each thing comes back to them. There’s a weight to words, and the weight for the Jew is very heavy, you know. It’s undeniable, words have the same meaning, but they don’t have the same effect for each of us. When we speak of death, for example, we speak with the memory of all our dead. When we speak of love, we speak of the memories, or the experiences, of love that we have. After all, that is normal. Whence the difficulty sometimes of speaking with another. Because we speak of the same thing, with the same words, but the things are different. When you’re speaking of sorrow, for example, while the other person speaks to you of theirs, you feel that there is really something between you, and then all of a sudden there is a chasm, because their pain isn’t quite like yours. While, when one Jew looks at another Jew, he knows his pain. That is something that is in each Jew. He knows. When one Jew meets another Jew, he doesn’t have to tell the story of his life, he doesn’t need to. That too is why, in these books, I didn’t want to tell these stories. I realized it was much stronger like that.

Converts can’t enter into that experience then.

They cannot. Because they convert for purely religious reasons, right. They don’t have this lived experience, which isn’t learned.

At the same time, Jews who convert to Christianity can’t escape it.

They can’t escape it. Max Jacob, for example, and there was a group like that, who thought they had to live the experience of Christ. That is, to begin by being Jewish, in order to arrive at Christianity, which is like the fulfillment of Judaism. I have letters from Max where he says, “I have always been tormented as a Jew and as a Christian.” There is a meditation by Max Jacob that I found where he says, “Thank you, my God, for having made me a Jew.” That is to say, “for having made me know all the Jew’s suffering.” But the real Jewish experience for me is not that; it is an atheist experience.

How do you understand Derrida’s statement that “Jabès isn’t Jewish?”

I understood it very well when he wrote it, because I don’t really know what it is to be Jewish. Judaism for me is a certain lived experience that I rediscovered through the book. And I realized that what I was saying as a writer was being received as a Jewish statement.

What is the significance of names for you, as in the latter volumes of The Book of Questions, with Yaël, Elya, Aely, El?

A name is the only manner we have to make our existence known to one another. If we’re not named, we’re nothing. So, this name, we assume it, we become that name. And that is the power of naming, it makes you exist and at the same time it effaces you. What is important in those names is the word “El,” which means God in Hebrew. But in the Kabbalah, when you invert the letters of a name, that is its death. So, Yaël, Elya, Aely, and El which remains. It is a way of showing too the effacement, by nothing but the words.

I’d like to return to the question of writing and something you said to Marcel Cohen in your book of interviews with him, From the Desert to the Book, that “at no moment is the novelist listening to the page, listening to its whiteness and its silence.” But is there not a certain compromise between the novel and the writing that you do?

Certainly. I’m convinced of it. Perhaps I said that in a manner that was too direct. What I meant is that the working of the text is not the novelist's concern. First, what he wants is for his characters to be able to speak loosely, as in life, imposing on the book something he himself wants to say. So, he prepares his characters, watches them live, and then he makes them live again in his book. The book may grow to such a point, as there are very great novels, that it becomes the story that it tells, giving a dimension that only writing can produce. But at the start it’s a way of proceeding that is contrary to my own. For me, writing is the adventure to live. And I live it as writing. I myself become a word, I become a phrase, and what the phrases say, they say it to me too in that way. My flesh is there, understand. While the characters that I have introduced, they themselves are only the flesh of the book. Because if there wasn’t all this questioning of pain and so on in and around, the characters wouldn’t have been able to be presented in this manner. So, everything that is their suffering, their life, isn’t told, but is done by this story of the book. It’s the book that becomes this story at such a moment, with everything it carries as questioning. The book comes to substitute itself for the universe, in order to become the universe itself. And in which I cannot introduce something, not a star into the sky. I must let all that happen. And in general a novel is situated in a precise place, one wants to write fairly specific things, to put characters into the scene that are quite precise. I don’t say that everything is premeditated with a novelist, because he lets himself be taken by the life of his characters, they live. But he uses words so he can tell what he wants to make known. He doesn’t let himself be taken along by the words, profoundly expressed by them. He makes use of words in order to carry across his story, to give life to his characters. That is the difference. The true writer does not enter into the book, he is in the book. While the novelist has characters enter the book with him, they’re imposed.

Yes, but it seems to me that a writer can . . .

Do both. Certainly. On the condition that he’s sensitive to that. But often they’re not. Because what counts is the anecdote, after all, the story to tell, whether it’s an unfortunate son, a love deceived, or whatever. Fine, he makes quite beautiful things happen. When he lets himself go, all right then, there we know the writer. At that point, the story little by little makes itself a part of the book, even if it is that of a novelist.

Since you say that everything in the books is lived, I wonder who is this writer who in El, or The Last Book jumps from the fourth story of the narrator’s building, and who in Intimations The Desert is found dead along the desert trail.

In short, it’s the image of the writer, therefore of myself. You know, writing sometimes leads to suicide, because it leads to the impossibility of speech, of the word. Many writers have written a lot about the impossibility of writing, right, which is absurd. Because if it’s impossible to write, how can we write? On the contrary, there is a possibility, but we only write in this impossibility, knowing we can neither really speak nor keep silent. We want to succeed, to go all the way there, but we know we shall never be able to. Each time there’s like an innocence, that makes us say, “All right, now I’m going to state . . .” It’s like this thought perpetually up against the unthought, and it forces the unthought finally to let go of something.

But it’s an image that seems to haunt you a little.

Yes, but it’s always the haunt of suicide. And it’s also in The Last Book because finally, as he has fallen from very high up, he constitutes nothing but a red dot. And this red dot is the title of the book. So, it’s to show how much this adventure of writing can lead to suicide. After all, every work is a wager with oneself. How do you explain, for example, painters who in full glory commit suicide? So, who have no reason to. Who have starved all their lives, all of a sudden they’re recognized, glory, one reads . . . ah, they’ve committed suicide. It’s something that’s between one and oneself. And no one can do anything for another. It’s a gamble. You see sometimes one passes hours on a word, and then one changes it for another word, which for him represents something entirely different. Most people don’t even realize, inasmuch as this word itself. But they realize after, in the general structure of the book. Because if there hadn’t been that, the book wouldn’t have been able to be said in that manner, it wouldn’t have had that force, that beauty, that harmony. But it’s a wager with oneself.

How do you work? You wrote much of The Book of Questions while riding the métro, for example, but what about now?

I do not at all work in a continual manner, it’s not possible. I believe I work twenty-four hours a day, but without writing. I write very little, that is to say, when I write a page, when it comes, that is a lot. But that page, it’s been four or five days at work, or six or eight months. I write by way of small pieces, but never leaving the book. Like Le Livre du Dialogue, I’ve written other things to the side of it, but this book does not leave me. It is in my thoughts all the time.

But can you hold on to more than one book at a time?

One thinks perhaps of several books, but there is only one that’s going to be done. Against all the others. And sometimes, for me, that is unforeseeable at the start. That is, I don’t know how this book is going to happen. All I know is there are a couple of phrases that have come. It was very evident in the poems. In Je bâtis ma demeure, I knew that when I wrote the first line the poem was no longer lost, I could go away from it, go to the movie theater, come back, I knew I was going to continue it. And I knew within a few lines how many pages it would be. Because I would feel it in such a way.

What was it about the métro that enabled you to write there?

Necessity. But it came at a point when I’d been carrying The Book of Questions in me for a long time. You know, when you do work that’s completely different, in relation to your own work as a writer, you are always a bit impatient to return to the writing. That has a double effect. It makes you suffer because you want to write and you can’t, because you’re obliged to earn a living and you have no choice. And at the same time it hastens the return to the writing. As soon as you can you try to benefit the most from this time left over, in order to write. But I realized something too, that finally the time of writing is very limited, that we don’t need a lot of time to write. Well, in the métro, as the book imposed itself, I couldn’t leave it anymore. I was really like a prisoner to something that demanded to be done. This journey between my home and where I worked allowed me now and then to mark things down, which remained either in the form of aphorisms, when they were really matured, or as the beginning of a page or two that I managed to write on Saturday or Sunday, when my time was completely free. Consequently, I can’t say the métro was a special place for me, it was the occasion. But I write the best at home. In general, traveling for me is a total cutting off from writing.

And when you were working in a job?

I was thinking of the book. And that is something that really astounded me, because perhaps it’s an ability to split myself in two. Even when I participate in seminars, when I’m speaking, whether of my books or not, when I’m answering a question, I have the feeling of not leaving the book. There is a continual listening. I’m not saying that all that is very clear, it’s not, but I know there is a work that continues to be done inside me. Because everything is useful to me for the book. My books are a perpetual quotidian. The most commonplace things have been very important for me. To such a point that I thought of keeping a diary, not to put the things I thought most important there, but the most ordinary things. I wanted to set aside everything that seemed important to me during the day, in order to keep the most commonplace things, that hadn’t even any significance. Because, I told myself, the important things must be left to work in themselves, they shouldn’t be written. We won’t lose them, because one way or another we’ll find them again one day, in another form.

Do you have any problem with beginning to write?

Well, I always delay the moment of writing. Often I do anything, chores, arrange books, hang up a painting, all that so as not to start writing. I feel that the moment’s arrived, and so at that point I’m taken with panic. I go out, I walk two or three hours, I come back and then, it’s as if I can’t escape something. And the moment I pick up my pen, I tell myself right away, it’s all over now, I can’t escape anymore. I’m caught in a trap. And at the same time, there is also a certain relief. But it’s not at all the pleasure of writing.

Do you know what you’re going to write at that point?

No. I feel there’s something that’s going to be expressed and I’m taken up in it. What starts it into motion suddenly is a phrase, and I know it’s going to start there. As if that phrase has opened a door to you. Valéry said, for example, that the title of a book or a text is the last phrase. That the first line is the last, like a mirror effect. But it’s after everything’s been done that that appears.

Do you have a preferred time of day for writing?

No. Perhaps now, in the last few years, it’s the morning. Before it was the night, very late.

Do you see any reason for preferring the morning?

I think that in sleep things set themselves in order, that a phrase takes its real form and comes back to you the next day. As if the truth were shaped or modeled in sleep.

Do you take any notes when you’re working on a book?

Never. Not a note. Each time I’ve always found myself at the beginning of an adventure.

You’ve said that with The Book of Questions there were at least three or four versions of each book. What determined the shaping of each book, how did the versions differ?

This is the way I work: I start writing the first pages by hand. When I reach ten or fifteen pages, where I correct these pages, I absolutely have to type them out because I can’t go any further. I need to have a certain lull from what has been written before. So, at that point there, I type out those pages. And I continue writing the rest, to correct the other pages on the typewriter. Then I take up the whole thing again, the pages already typed out but corrected, plus the new ones that weren’t in the typewriter, and I type out the whole thing. And then I correct the whole thing together again. That is, there’s one correction directly with the text, and each time I add more pages there’s a new correction, because it’s what the other pages contribute that shows me that either there are things missing or that are too much. And the book is done in that way. There are three or four, sometimes more.

How have you known when you’ve reached the end with each book?

I never knew. It’s never the end. It’s the end of the book, that is it’s always unfinished, but it’s where I feel I cannot go on anymore. I feel it.

Have you, by the same token, found that the beginning wasn't the real beginning either?

Well, yes. In all these books, there is “The Fore-Book,” “The Before The Fore-Book,” and so on. That is the book we carry in force. And it’s always the beginning that isn’t one. It’s the book that is in the act of becoming, but itself doesn’t know how. That’s why I kept them, they’re like rumors of things that are coming. And then, the book takes shape.

What are some of the readings that have been important to you, after Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Max Jacob?

First of all, the reading of poets. But, for example, the reading of Maurice Blanchot, who is someone that is very close to me. And the writers with whom I have affinities, philosophers like Jean Grenier, Emmanuel Levinas, Derrida, writers like Blanchot, Michel Leiris, Gabriel Bounoure, where there was also a questioning of the book inside.

You’ve described Blanchot’s attitude that certain friendships have “nothing to gain in a tête-à-tête, that the silence in which they bathe must not be broken, even in their strongest moments.” What happened when you met?

I’ve never seen him.

Still?

No, we don’t know each other. For Blanchot what happens in absence is much more important than the meeting, much more intense. And in effect, the correspondence that I have with him is very intense, very strong. Because it is at moments that are quite precise. I have never met him personally, but he remains very close to me.

You’ve never spoken with him on the telephone?

Never. I tried twice to see him, but he didn’t want to because, well, I respect his position a great deal. I understand quite well that our meeting would only bring a momentary pleasure, after all, to see each other, to shake hands. But on the one hand, there are the books, and on the other hand, now and then a sign that takes on all its importance, because, as far as I’m concerned, I only write him at very important moments of my life. So, I know that he exists, I know that he’s there. And he knows too that I’m here, on this side.

There’s a writer who so lived his book he was consumed by it, which is Proust. What did you find in Proust for yourself?

First of all, memory. His work about the memory. And then, the great movement that Proust’s books carry, which is very close. That is, there’s a proximity in what is the essential for me. It’s not in the characters and the anecdotes, although he was saying things that join up again a lot with what I have been able to say. But it’s above all in his conception of the book, which for him was also not at all premeditated. One is swept along by these books like that. Because after all the whole pursuit is, for me too, one single book. Obviously, Proust’s writing is entirely different, but it’s carried along like mine by the breath. You know, we work with the heart and the soul, but we work with the body above all. The body imitates the writing. It’s curious, he suffered from asthma, like me. Asthma has made me have to put in blank space sometimes, so that the phrase could breathe, because I’m suffocating and I feel that the phrase is suffocating. So, that led me to the aphorism, out of necessity. He carried the phrase on and on, until he ran out of breath.

What has been the academic and critical response to your work?