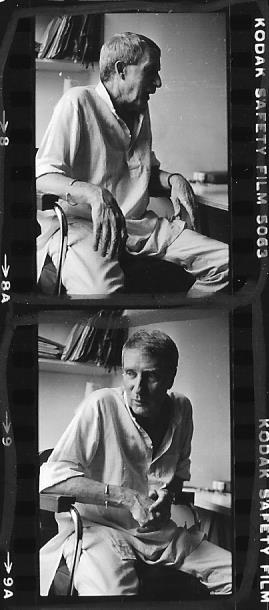

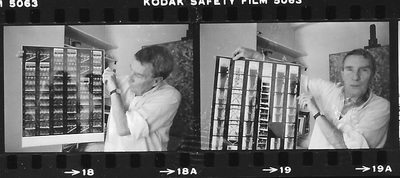

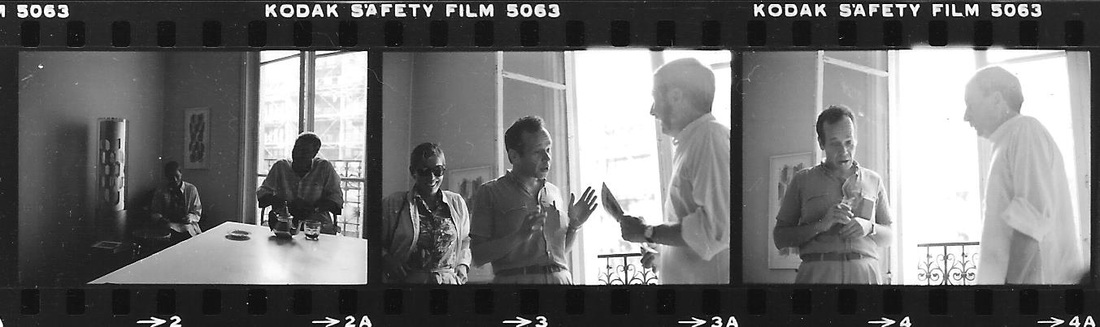

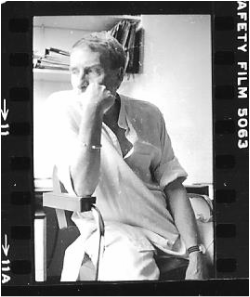

Photos: Sean Newton

Photos: Sean Newton

Brion Gysin

Portions of the first interview appeared in the International Herald Tribune (October 4-5, 1980), and then the complete text in Reality Studios (London) 4:1-4 (1982). The second interview appeared first in French translation in Jazz Magazine (Paris) 300 (September 1981); in English, excerpts came out in Invisible City (San Francisco) 28 (1981), and the whole thing in Quilt (Berkeley) 4 (1984). The third interview appeared in Marc Dachy’s French translation in Luna Park (Paris), nouvelle série, 1 (2003). All three interviews were published together in Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (Iowa, 1991), now out of print.

I.

Painter, poet, inventor, Brion Gysin (1916-1986) was also a historian, novelist, songwriter,and general instigator. From his early book To Master, A Long Goodnight, including a history of slavery in Canada which won him one of the first Fulbright fellowships in 1949, to his discovery of the cut-up technique of writing, which William S. Burroughs put to good use (their collaborations were finally published in 1978 as The Third Mind), through his invention of the Dreamachine and being a pioneer of sound poetry with his permutation poems, Gysin was a multi-media visionary. This seems especially evident in his two novels: The Process (1969), drawn from his years living in Morocco, and The Last Museum (1986), based on his extended residence at the Beat Hotel in Paris, where many of the Beat generation stayed during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Gysin was an artist who made things happen. For a man who could handle seven languages, his true métier was language in all forms. Writing and painting crossed paths repeatedly throughout his life. His écritures or writing paintings—the most abundant mode in his visual work, starting in the late 1950s—often juxtaposed Japanese calligraphic lines with a modified Arabic line; together the two strands formed a textured grid that had the magic of a written language.

Born in London of Swiss-Scottish parents, Gysin grew up in western Canada, until he was sent to school in England. At the age of eighteen he left for Paris, where he soon showed his artwork in the famous Surrealist Drawings show of 1935, only to be taken down on opening day. As the war approached he traveled to Greece, and then to America, living in New York mostly; in 1949 he returned to Europe and eventually, at the invitation of Paul Bowles, he went to Tangier. Through Bowles, he heard the Master Musicians of Jajouka, whom he much later introduced to Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones and also to Ornette Coleman. Gysin was so enchanted with their music that for several years he ran a restaurant in Tangier called The Thousand and One Nights, which enabled him to employ the musicians and to hear them every night.

Through the years, Paris remained his most constant home. The first part of this interview took place in August 1980, at his apartment directly across from the Centre Pompidou, the museum commonly known as Beaubourg. At the time, he had renewed hopes of at last making some money from the Dreamachine, which he co-invented twenty years earlier. The five-foot-high contraption was not a complicated device; it consisted of a transparent cylinder encasing another slotted cylinder that turned by a motor around a light bulb, flashing stroboscopic pulses of light. The viewer gazed in with the eyes closed.

Gysin died of a heart attack at his home in Paris, at the age of seventy, in July 1986.

How does the Dreamachine work? Can it be described specifically?

Oh yes, very scientifically. I had the actual experience, in the back of a bus, driving along a row of trees that was spaced exactly as was necessary to produce the effect with the sun setting behind the trees. I closed my eyes and had what I thought was a spiritual experience. Like Mr. Saul on his way to Damascus about to become Saint Paul, same thing happened to him and presumably for the very same reason. He must have been riding on the back buckboard of the chariot like that, and gone down a row of trees, horses going at just the right speed, and he closed his eyes and saw all those crosses.

The present version of the machine, which is being made by the Swiss in a limited edition of twenty, is a sort of optimum pattern of an open cylinder. What we had done originally was a cylinder with just the exact slots. Then I made one like a coliseum where each row was a different speed. Later, I developed the current one whereby the incidence of curves produced every one of those gradations between eight and thirteen flickers a second, because that’s where it is, in the alpha band. In fact it is a complete exposition of the alpha band. You see so many things in there, after the hundreds of hours that I have looked, that you get to a place which is real dreaming, where apparently it affects the very back part of the original bottom brain or somewhere like that. The only person it ever happened to the first time around was old Helena Rubinstein, with whom I had a long romance about the Dreamachine. Madame would say, “Oh yes, I had a boat trip. Oh yes, I’m in a speed boat between Venice and the airport. Oh, I’m taking the train in Venice.” And so on. She’s the only person I’ve known who really just saw them all like movies.

But I would go even so far as to think it’s possible that everything that can be seen is seen only in the alpha band. Because you see all the religious symbols, you see like dreams, like movies. Maybe that’s really all that we can see and that’s where it’s stored in our brains, within that range of the alpha waves.

What brought on the realization that this dreaming might lay within the alpha band?

In the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, when they first had an electroencephalograph, scientists discovered the alpha band of brain activity. They showed that it changed between eight and thirteen pulses, or interruptions of light, per second. Below eight, for example, you’re down into deltas and thetas, which give you a very luggy, unpleasant feeling, maybe like these ultrasound effects that people are talking about. We read that out of a book by Gray Walter, an American from St. Louis who happened to work and spend his life in the Bristol neurological center in the west of England. He was the man who invented the thinking mouse, the toy mouse that could learn. He made the thing electronically in such a way that it could not just run to a certain number and back again, it could make a mistake and then correct the mistake. William Burroughs went to a lecture of his. He never had any other effect on me except that one thing he said, just in half a sentence, that people who are subjected to interruptions of light between eight and thirteen times per second reported experiences of color and pattern. I said, “Oh, wow, that’s it!” Ian Sommerville was back studying mathematics at Cambridge and I wrote him and said, “This is the problem. How can we make it at home? How can we do it with just what we’ve got?” So, when he came back to Paris the next holidays to the Beat Hotel where we were staying, we didn’t have enough watts. We had three rooms, Burroughs in one room, Ian in another, and me in a third. We sort of ran wires loose out the windows and everything so we could get enough. That’s where it first started, we made some very beautiful machines that got lost. Ian was very good with all that sort of cutting and handling, very expert.

So that has evolved up to the current version of the machine.

It’s gone much further than anything he ever saw. The last things he saw were more like the one that’s over in the Pompidou museum. They bought one and I agreed to call it a prototype.

Did all the earlier versions work along the same lines?

They all produce the same effect, but this is the ultimate artifact, or pre-ultimate. It’s being handled by Karl Lazlo, a big private art dealer and enthusiast. He wanted to do something with me, and we came to the idea that he would just occupy himself with the Dreamachine. Because it takes quite a bit of doing, to get all those pieces made and all. Nobody wants to do it anymore, bending plastics and such, it’s very difficult to find anyone.

What about mass production?

Mass production has always been the question, even in the 1960s. First, Phillips was interested in the idea, and some people in America, and toymakers. When they looked into it, they found that the least they could begin with—that was 1965, a long time ago—should be fifty thousand units. Where were you going to get fifty thousand little motors? What size was it going to be? How were you going to package it? Above all, how much shelf space was it going to take up? Because then you imagine fifty thousand boxes that big. Well, you could put so many diamond bracelets in that space and make so much more money. Those are the sorts of things that held it up for all these years. I have all those problems stored away in the back of my head. So, the first real breakthrough was Lazlo saying, “Yes, I will do it, I will make this number.” Because naturally one would like to make a smaller model, like a sort of bedside lamp, for example. And I’m not at all sure that I’m necessarily going to profit much from this. But I’m sure that it’s going to happen at some point or another, I’ve known this for twenty years.

Did you have one in Tangier?

I never had one working there. Because by the time I got back to Tangier from all these hassles and wrassles . . . I was ten months meeting all those people, everybody from sort of ethical culture toymakers to real crocodiles in the slew of the swamp type toymakers. I mean, they’re a horrendous lot and weirdo people, really very strange. I got to know their problems, at least they explained what it was. It wasn’t a question of selling them on the idea. They got the idea right away. But then how do you actually do it, whew!

Have you had any retrospectives of your paintings in Paris?

No, only one small one that was put together by some friends of mine. Because I swore I wasn’t going to come back here, this is foolishness too. That’s why my situation is like it is. You’re supposed to be here all the time, you’re not supposed to go running away for twenty-three years in Morocco. Or if you’re in New York, you’re supposed to be on the New York scene and be part of the show, in a way. That’s what you’re getting paid for, to be there to be part of the show. And I have sinned against all these things. Stupidly, in some ways. I realize it’s a hangup. But these things are sort of getting ironed out just very late in life. It’s lucky they’re being ironed out at all.

But wasn’t it your own interest that took you to other places?

Yeah. It was also that whole Beat Hotel thing, from which the Dreamachine came and from which the cut-ups came. William managed to get his ass out of there. Then we went to America and put together The Third Mind in 1964-65. And then both of us decided we couldn’t make it in New York, and so we came back to Europe and William set up in London. I said, “Oh, I’d sooner die than live in London,” and I went back to Morocco. I really left Morocco again only in ‘73. I left because friends of mine with whom I had left all of the écriture canvases, which were all done at the Beat Hotel between 1959 and 1963, and lots more, they put together a show—like an homage—in a gallery on the same street next door to where the Beat Hotel was, on the rue Gît-le-Coeur. It was really from their hearts that they’d done it, so I was very impressed. I said, “Oh, I’ve just got to come back and take care of the store,” that’s all. I came back and then I got sort of mowed down by cancer and knocked out of the scene for a while. So now I’m just scrabbling again. Things are definitely coming together, but they’ve been hung up for twenty years.

Are you still painting?

It’s almost ground to a halt, I must say. First of all, because I started writing more. Also, because it just wasn’t working. I didn’t have a gallery, I didn’t have an income from it. Then, oddly enough, my work slipped off into photography.

How did you arrive at doing your écriture paintings?

Well, it turned out that everybody got this sort of message of calligraphy. It came to me through the war, because I was a translator of Japanese. That’s how I got interested, it wasn’t from the point of view of painting at all. After the war, I came back here as a Fulbright fellow—not as a painter Fulbright, I mean as a writer, historian. During the war I met a cat who was the great-grandson of Uncle Tom, the man who told his life story to Harriet Beecher Stowe. And so, I wrote a book about Josiah Henson. From there, because the escaped slaves went to Canada and founded agricultural colonies there, I wrote the history of slavery in Canada. It was on the basis of that that I got my Fulbright. Later, about the same time I was doing the repetitive poems, I was looking for something that would repeat graphically. In Rome in 1960, I found a housepainter’s roller which I then re-cut to produce this (shows a print which bears a curious resemblance to the exposed structure repetitions of the Centre Pompidou). When I saw the plan for this museum, I said, “Well, it seems to me that back in about . . .” So I became very interested in this place across the road.

Had you been living in this apartment since before Beaubourg was built?

No. The frame was up when I moved in here. So, I started photographing Beaubourg. The whole idea dates back to 1960. Then I realized that the camera is also a roller, that what is inside it there is also a roller. I began in black and white, and then I moved into color. Then I decided that I would jump inside the camera and count, just like the roller counts. The series of photos begins by being taken out of this window here. I got the idea in this room, what I can see from here. And then I put it together again (section by section, shot by shot, to re-form the whole view of the museum). And then, just studying the elevators, using it the way I used the roller, as blocks of ink or whatever. And then I go around the building, take the escalator from behind.

How was it you came to learning Japanese?

First of all, I started out in the American army and it wasn’t working out very well. I saw that I could easily be shipped out into some fucking Pacific island or something. So I made great efforts to try and do something. I joined the paratroopers and then I broke my wrist on the very first training jump.

Why did you join the paratroopers?

It was a gas, man. Everybody worthwhile was there, it was a great gang of people. Real crazy, every hothead insane person from the East coast was there, and the South. Anyhow, that didn’t last very long. So I went off and got myself a transfer to the Canadian army, by all sorts of finagling around. It was they who started me on the Japanese. I said, “Oh no, what have I stepped into? I have great respect for these charming people, but I’m not learning it all.” Really, the only thing I got out of it was the way of holding a brush, and the use of a brush, the language of a brush. The whole business of running ink on the paper.

Did you study painting in school?

No! I wasn’t allowed to have any painting lessons. In fact, to this day I can’t imagine what anybody learns in an art school. I’m sure there are very useful short cuts and stuff like that perhaps, handicrafts. And it is a bitch to have to teach yourself, that’s a fact.

How did you come upon the idea for your écriture paintings?

I had had a very unfortunate experience with magic. Somebody had done me a black magic thing, and I’d actually had the cabalistic square of paper where you write across this way and then you turn the paper and you write across the other way, and then you’ve got the thing locked in and it happens. I thought, yeah, how about using Japanese calligraphy in this direction, without turning the paper, and then just running an Arab line across it, and so I had a grid. That’s how it all came into being for me.

You can look at those paintings from any direction.

That’s right. And then I ran into the idea of the permutations in poetry. So I carried that over to painting, where I had a grid and then I cut and permutated it to make a big picture.

Is it all actual writing in the écritures?

You mean, can I read it and it says so and so? No. But it has most of the sort of magic elements of writing in it. The attack of the brush to the paper.

Jackson Pollock was also doing a sort of writing, écriture, in dripping the paint.

Sure enough. This was very much in the whole line of what was happening to painting itself. Painting as image was being eaten up by Picasso, let’s say, he was the last cannibal. He ate up all the images, he chopped them all up and did what he did. Then people began to be interested in the matter—what the French had always been talking about, la matière, the stuff—and would say, “Well, let’s play with the stuff. What does the stuff do?” It was very much in the air.

Do you know how to write Arabic too?

Yeah, but I never learned properly. As with Japanese, the real reason there was because I thought, “Oh, if I really learn this properly, then I will be writing sacred texts.” I didn’t think it was a very good idea. It’s funny, in that book of Dizzy Gillespie’s (To Be or Not to Bop), he says, “There’s only one thing I really regret in my whole life: somebody once got me to put on a funny turban and pretend that I was praying to Mecca. Because I realize that I was making fun of these cats and it isn’t at all what I meant. I think a lot of the trouble I had came from that.” Of course he’s right, a lot of the trouble came from the image as it went out, his whole public image changed. They were going, “Ah, he’s one of those Muslim cats,” and so he got less work.

I’ve always been at least partially inventive as well. It doesn’t please me unless that’s involved. So, in a way getting into photography became a bit of a dead end for me, as far as the visual work was concerned. That’s why I jumped on all the writing stuff I had hanging up.

What got you into jazz?

Gee, it’s kind of a sad story. I’ve been thinking about that recently. In those great 52nd Street days I was always on the wrong side of the street. I was always at the Cloop or Tony’s or whatever, which was exactly the opposite. I’d just go dashing over like that to ask Billie Holiday where to score and I remember, John Latouche and me, she gave us the key to her flat. We took a cab wa-ay uptown, you let yourself in, and on the piano there’s this great big lamp. You unscrew the lamp, and reach in, and you find a couple of joints. And instead of sitting at her number, really, ‘Touche would drag me back to listen to something he had written for a Broadway show that he was going to be doing. He couldn’t read music, but he could really hammer away and imitate everybody else. I spent all of my musical time in New York on Broadway, because I worked on Broadway the first two years I got there. I was Irene Sharaff’s assistant on a whole bunch of musicals: By Jupiter, Lady in the Dark, Banjo Eyes.

How long were you in New York?

From ‘40 to ‘49, with time away in the army. And naturally, because of the way it turned out for me, I heard less of bebop starting. And I heard of William S. Burroughs only over the telephone. Because John Latouche had a German secretary, who was William’s first wife. She wore a monocle and sort of mannish tweeds. William had married her in Athens, as a matter of fact, just to get her entry into the States. By this time she was working for John Latouche. John had made a whole lot of money from Taking a Chance on Love, and Cabin in the Sky, and those sorts of things. He’d say, “I’m making more money than the President of the United States,” and “If you don’t throw your money out the window, it won’t come in the door anymore,” things like that. He really lived like that, zoom! And he wouldn’t be bothered, dig, with bebop. One day I was at ‘Touche’s house and the telephone rang, she goes to answer it. And ‘Touche says, “If that is your husband William Burroughs, don’t let him up here because he’s got a gun!” And I thought, “Who-who’s this William Burroughs? I mean, she’s married to the man. Come on, he must be kidding.” He says, “Yeah, yeah, she’s married to this dangerous lunatic and I don’t want him up here.” I said, “Ooh.”

That was the first time you’d heard of him?

First time I ever heard of him.

With your permutations, and the other work using repetition, had you been influenced by any of Gertrude Stein’s work?

Well, it was considered anti-surrealist to frequent Gertrude Stein or Cocteau or Gide, or any of those people, dig. Maybe that’s how I got thrown out of the surrealist group. I mean, what were the terms? It would have been some kind of court-martial for bad attitude, something like that.

Because your interest was more eclectic.

Right. I never did dig those autocrats setting themselves up like that. Anymore than Virgil Thomson in New York, where I got to know all the classical composers, everybody in that whole gang. Except Henry Cowell, who was the most interesting, he was away. He got a seven-year rap for advances to a sailor in a toilet in San Francisco. Seven years!

How close was your novel The Process to life in Tangier? Do you remain in touch with the people you knew there?

Hamri, who is the hero, villain, and mainspring of my novel, he really exists. In fact, he exists so strongly that just this very morning he came bouncing through the mail. In the book he’s just called Hamid, but everything in the book is true. Everything! (Reads:) “Dear Brion, I look for mail from you, please! Ali is complaining too. I don’t want God to complain also. Regards, greetings, and my finest salutations, from Hamri, the painter of Morocco.” And this is coming from Santa Monica to me. So, we’re all still in business together, it looks like. The musicians are all his cousins and uncles and everybody like that. They are one family of the Ahl-Serif tribe and they live in the village of Jajouka. It’s a village that must have once been an important military post, say, in Byzantine times, inasmuch as from it you can see Larache, the first good port of any size on the Atlantic, and was the site of Lixus, the Roman town and the Greek city. The golden apples of Hercules were there, growing presumably on an island in the harbor, attended by a group of prostitute-priestesses, a traditional thing that had come all the way from the Phoenicians through the Carthaginians. From that village you control the pass up into the mountains, which dominate that whole valley, that whole seaboard, of the Rif Mountains. So, these people remember exactly who was related to whom in the year 800 when the first prophet of Islam came there and they all became Muslims. He is buried in the village and so they call themselves his children; they are the Ahl-Serif, the sons of Serif, who was buried in the tomb there. And around him they do musical therapy. They cure mental disease and anxiety through a musical experience where the patient has the sensation that he smells a very beautiful smell. The musicians produced this for Ornette (Coleman). A real wipe-out session occurred where twice this sensation was produced, everybody had this overpowering sense of the perfume. William Burroughs wrote a nice little piece about it for Penthouse.

How did you first come upon the Jajouka musicians?

I heard them in 1950, thanks to Paul Bowles who was a key figure in all of that Moroccan experience. He’s got his Morocco like Somerset Maugham has his Java or whatever. It has nothing to do with my Morocco personally, at all.

Were the foreigners all part of one scene when you were there?

Well, it was a colonial world, a real holdover, you were living in and breathing the past. The further inland you went, you were breathing even medieval times, in Fez still. I mean, I’ve lived in the time of Chaucer. I’ve actually lived morning, noon, and night with everybody around me dressed and looking like they were doing things out of Chaucer, in Fez. In Tangier, it was an atmosphere that nobody has ever really caught yet.

How did you come upon the permutations idea in the late ‘50s?

Well, mine was a knockout discovery for me. In The Doors of Perception Huxley quotes the famous divine tautology, “I am that I am,” which is supposed to be what Jehovah said. If you’ve read Velikowski on the subject, he thinks there was an actual event that took place over a period maybe as long as twenty-five years in the third millennium when the whole Sinai desert did say, “I am that I am I am that I am (speeds it up into abstract sound).” That it had the sort of vibrations that were happening in this idea. Velikowski thinks that what we now consider Venus was a comet that entered the galaxy and then got caught into our system, but as recently as that, and that there is a folk memory of that time. I have carpets hanging up that do bear him out, the starry serpent runs through them. This pattern comes from the Berber mountains in the south of Morocco, and it goes to Mexico and so on. Well, he says there was actually an event when Venus did the zigzag followed by a trail of zigzag meteorites and everything, for a period of about twenty-five years in the third or fourth millennium, and that people really remember it. And that at that time indeed, the desert, you could hear it saying, “I am that I am I am that I am (speeds it up),” and that’s where the whole idea came from. So, I saw the phrase on paper and I thought, “Ah, it looks a bit like the front of a Greek temple,” only on the condition that I put the biggest word in the middle. So, I’ll just change these others around, “am I,” in the corner of the architrave. And then I realized as soon as I did this, it asked a question. “I am that, am I?” And I said, “Wow, I’ve touched the oracle!” So then I turned the next one, and I said, “Oh, all the way along it has to do this.” Then I did those two versions on tape with the BBC in 1960. One is like this, it goes around, around, and it goes out, out, out, further out, out, and ends quiet. The other one has a voice that begins very slow and comes in, and then two voices come and fight, and then go out.

Are there recorded copies of this work?

That work is scattered, and not united at all now. “The Permutated Poems” was a twenty-three-minute program and I don’t have the whole tape of that. Because that has the very important pistol poem in there. I came to the BBC with a beautiful shot of a cannon that I had recorded in Morocco. And they said it was too long, which of course it was, we had to get something sharp on the tape. They said, “We have a pistol here that we use for haunted houses, murder scenes, and things like that. Would you like to hear it?” I listened to all of their pistols and I picked one. I said, “Record it for me at one meter away, at two meters away, three, four, five. And then we just play them and we permutate that. Then we take the whole thing and double it back on itself like that.” And it was, “Oh . . . wow . . . there . . . ah.” So it took quite a while to do, as you can imagine. That whole piece was unfortunately cut up and the whole thing as it’s supposed to be doesn’t exist anymore at all.

I’m surprised that all that isn’t together.

I haven’t been minding the store!

Around 1960 you invented the cut-up technique of writing. While cutting a mount for a drawing, as you described it, you sliced through a pile of newspapers. You picked up the raw words and began to piece together the texts. At the time, you said that “writing is fifty years behind painting.” Has it caught up at all since then?

Well, I also said, “Should writing try to catch up?” But look at what’s happened to painting even since I said that, some twenty years ago. Poor painting herself is just tottering on the edge of the precipice, or maybe has already fallen in, where it’s all become deceptual art. Anybody can do it because there’s nothing to be done except just sit there, for example, or wear a certain kind of clothes and do these public performances. So, art as painting has really disappeared. Nobody wants to see paint properly applied to canvas anymore, that’s considered very old-fashioned.

How do the cut-ups differ from what Tristan Tzara did?

Particularly because there’s an actual treatment of the material as if it were a piece of cloth. The sentence, even the word, becomes a real piece of plastic material that you can cut into. You’re not just juggling them around, or putting them into . . . Tzara’s words out of a hat were simply aleatory, chance.

Doesn’t the personality of the writer become diminished in the cut-ups?

Oh no, I think it becomes multiplied. There’s a long interesting piece that Burroughs wrote, where he speaks of plagiarism, simply sort of taking on the spirit of the person whose work you’re handling. Becoming a Rimbaud, or becoming a Shakespeare, partially so. Obviously, those are roles which are given to the writer. He has all the rights to those roles, after all.

Were the sound poets active now hearing what you did back in the Beat Hotel days, with the permutation poems and your use of tape recorders?

Oh, sure. And all the repetitive musicians too heard those things. The only one who’s ever come up on stage and said so to me is Phil Glass. But I’m sure the others heard it too.

What pieces of yours were they hearing?

They heard “I am that I am,” and “Calling all reactive agents,” and “Pistol Poem.” Because “Pistol Poem” was played a lot on the radio. When the permutations were laid one over the other like that, it goes off into 4/4 time and becomes a crazy little waltz. By itself! So, the whole point of it, and anybody who listens to it sees, is the idea that you just put the material into a certain risk situation and give it a creative push. Then the thing makes itself. That’s always been my principle.

Were you writing at an early age?

Yeah, everybody was writing around my house. But I’ve always found that it’s impossible to do two things at once. If you’re really into one thing, you have to get into that a while. Sometimes it’s only because your household isn’t laid out right. Because if you’re living in such a small space, if you’ve got to write and cook and eat on that same table, you live one way. And if you’ve got three rooms in which these three different things happen, then you do it another way. If I had my setup here, plus a studio room, then I could be very different. There are reasons for investing more of one’s energy in an ongoing enterprise than in one that seems to be standing still for a while. The Third Mind had begun to happen in 1959-1960, and it had actually been in the form of a book since 1965, though not as it is today. It appeared in French two years previous to the English language edition, and the big help came from Gérard-Georges Lemaire here in France. On the other hand, some enterprises are presumably hopeless right now, like Naked Lunch as a film.

What ever happened to your screenplay of the book?

At the time, William said it couldn’t be done. Anthony Balch wanted to make the film. As it turned out, with the kind of money we could put together, we would have to do it in England. The script is still very funny. It was written with the idea that Mick Jagger could do it, or anybody, David Bowie could play it. I discussed it with Milos Forman, over dinner at La Coupole, and he said, “I will never have anything to do with sex and drugs!” I said, “Well, what are you going to do?” He said, “I’m going to do Hair.” You can imagine the script anywhere, as a kind of nostalgic Hammer film, like those English horror films that were so great. It begins in an English country house where William is really kind of old J. Paul Getty, and it gets funnier and funnier.

II.

As a song lyricist, Brion Gysin worked on several projects. His most abiding collaboration was with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, whose sextet recorded the album Songs (1981). Lacy’s group also toured another set of Gysin songs as a ballet, Stuff, playing in France and Italy, but the music was never recorded: the lyrics were part of Gysin’s screenplay of Naked Lunch. Gysin did record his own solo album, performing most of those lyrics, Orgy Boys (1982). He already had sung on the Lacy record, with the bawdy “Luvzya,” in duet with drummer Oliver Johnson. Later, he recast some of his songs and wrote new ones with the guitarist Ramuntcho Matta. On a single they recorded “Junk” and “Kick That Habit,” among his original permutation poems, playing with trumpeter Don Cherry, plus a bassist and drummer. Then they recorded one side of an album under Gysin’s name (1985), performing in several Paris concerts (all of the Gysin/Matta collaborations were issued posthumously on CD as Gysin’s Self-Portrait Jumping). At the time, he liked to refer to himself as the oldest living rock star.

The following interview with Gysin and Lacy, on the occasion of their album, took place in May 1981.

Steve Lacy, you were setting painters’ texts to music and through that you found Brion. How did you know of him?

SL: I guess I knew he was a poet-painter.

BG: We met through Victor Herbert, and then again at the American Center in ‘73.

SL: In ‘65 in London, I had heard recordings—at that time they called it electronic poetry—and some of Brion’s stuff was on there.

His permutation poems?

BG: It must have been Henri Chopin’s record, OU.

SL: I thought it was amazing, I really liked it. I had been thinking in . . . not with electronics, but some of the results achieved.

Did that tie up with any jazz roots for you?

SL: Well, jazz is speech rhythms. It’s like parlando music. And it all comes from phraseology anyway, it’s just a language. So, when I heard that stuff, I found it exciting.

BG: My opinion is that Dizzy Gillespie hasn’t been recognized as a great sound poet.

SL: Absolutely. No question about it.

Your whole interest in that seems unique for a jazz musician.

SL: Well, you could find little snippets of that in many people, back to Louis Armstrong. You can think of Fats Waller and Billy Strayhorn and Ellington, and then to people like Red Allen and Roy Eldridge. Well, many. I think what I did was dig a certain vein a little bit wider or deeper than is customary, but it was nothing new on the scene really.

Brion Gysin, when did you first know of Steve Lacy?

BG: I’d heard his music and heard records, it must have been about ‘59 or ‘60. That was the moment jazz and poetry had suddenly arrived and been talked about in New York in 1959. There were a couple of efforts at this made by Gregory Corso and others. I didn’t think it worked at all. Then in Paris I met a group of poets called the Domaine Poétique. We had possibilities to do anything we wanted. That went on 1961-64.

What was your first collaboration?

SL: The first thing was “Dreams.” The music was written in ‘69, and I asked him to give me the lyrics in about ‘73 or ‘74. By that time I knew he was the inventor of the Dreamachine. And that really struck me. I had this piece called “Dreams,” and it was a melody that came to me in a dream in Rome. It was written to Italian lyrics by Falzoni, but it never got off the ground. But the melody was haunting. So I thought Brion, being an expert on dreams, might be able to supply me with the necessary lyrics, in English. And he agreed. He came up with the most fantastic thing, really, the lyrics are out of sight.

The music was what it is now?

SL: The melody was identical. But the bass line and some of the inner voices took a while to work out, quite a few years.

Brion, when did you first start noticing jazz?

BG: Oh, I always noticed it. I used to be very snooty about it too. I remember saying, “Well, it’s all very well, but they’re improvising on tunes that don’t interest me in the first place.” That’s where I stood, on the wrong side of the street. But I knew I was hearing both sides of the street.

Later, in Morocco, Paul Bowles and I were sharing an Arab house with a high tower where you could get very good reception. He had a good radio and we used to play nightlong games of listening to German jazz, Japanese jazz, Australian jazz, and all sorts of things you could get on short wave.

Also, in New York, Latouche did a rather disastrous show together with Duke Ellington, Twilight Alley. I went to Duke Ellington’s house and saw how that whole music machine worked.

Was there a musical imprint that you intended on your new record together, Songs? It seems on the edge of various styles. There are strains of Kurt Weill, for instance.

SL: Well, I’m aware of all these people and what they’ve done, and Weill was a big influence in my own work. But one thing that’s been a strong factor in this is my own desire to insert serious lyrics into the jazz fabric. It’s like a search for quality. To raise the level of the lyric, so you have something good to play on. Because we play with those words. When we play those tunes based on Brion’s words, all the music comes out of the words. I’ve been lucky to have Brion’s stuff to work with. For me it was a miracle finding stuff already made of that quality. Like when he gave me the words to “Dreams,” it came out perfect. Then I wanted to see what he had already done. He showed me this stuff and read it for me, and I thought it was great. Because it seemed like it was already set. Just the way he would read it, I could hear it in a certain way that it was already pitched. So I just had the fun part of mulling it over, listening to tapes of him reading it, and finally fixing the pitches and everything myself. And then to getting them realized is a long step and that involved, well, learning them.

BG: That’s right, I was just knocked out, in this photograph taken by Hart Leroy Bibbs during the recording session I’m just in a state of sheer ecstasy. And it’s because, when it was all put together like that with the sextet, I heard my own voice coming right through there in the whole thing.

How far back does the earliest song date from?

BG: Well, in the ‘40s, I had a project for making a musical out of the biography that I wrote of the man who was the original Uncle Tom, Josiah Henson (To Master, A Long Goodnight). And the only one from that period is “Nowhere Street.”

What had you written of that project?

BG: I wrote the story and the lyrics. The story was as it really happened, not the way Harriet Beecher Stowe saw it. In other words, how it led him on to all that and how he got kicked in the ass in the end by his name becoming the most pejorative one of all. He never thought this shit was going to fall on him like that. That was the way the musical was supposed to go. And “Nowhere Street” was . . . there’s a separation with his great love, he’s decided to make it north and she’s left in a kind of deserted town like Cincinnati, a suburb of Cincinnati in 1850, where “Nowhere Street” was. She comes on stage and the leaves are falling and lights are coming on in the houses and going off in others, mysterious, a kind of haunted house sort of thing, and frogs croaking.

How much of that did you see when setting the music?

SL: I never heard this part about Cincinnati before. But Bobby Few (piano player in Lacy’s group) is from Cincinnati.

BG: No shit!

SL: But it’s apparent in the lyrics. They’re so vivid in their painterly abilities that the whole thing is right there for you.

Do the Jajouka musicians of Morocco seem to be any point of contact between you?

SL: Yes. Brion hipped me to that whole thing—the music I’ve heard, meeting some of the people, and playing with the President. It’s been sort of a good glue between us, reinforcing other things. I’ve gotten into it as far as I could in the time. But it’s a trip. I would have to go there and give up everything else . . .

BG: Like me. Like I did.

SL: . . . And get to it. And I’m not about to do that.

BG: He’s scared.

SL: I’d like to go in a helicopter, stay for a few days and get out of there, you know, when I could.

BG: Like me. I stayed all the time there because of that.

SL: It would have been wild to hear Trane play with them. But maybe in another life or something, in another world.

When the two of you perform together, what establishes the time?

SL: Well, what we do is like when the songwriters do a demo of their tune. The lyricist sort of says it and the other guy sort of plays the melody, but shifting a little. So it’s not strict time. Sort of collapsed here and stretched out there, so it gives you an idea of how it might sound.

BG: Here’s the poor author standing in the crook of the piano.

SL: Like an art pauvre. No, sometimes it really comes out perfect, where it’s not exactly sung but heard. A kind of delivery.

BG: This is where you’re standing out there in front of twenty prospective backers and their girlfriends.

SL: Yeah, they got the singer next to them and the money in their pockets. “These guys wrote this song. Honey, you think you’d like to sing this? I’ll buy it for you.” . . . But where we usually do it is poetry festivals, where any kind of a musical phenomenon takes it out of the level of the ordinary there.

What is the role of improvisation between the two of you?

SL: In his work, I found it to be very jazz-like, in that he was living it. When he delivers it, he’s playing. It’s different each time. It’s delivered in a free, improvisational manner, and that leeway is written right into it.

BG: And things that I’ve written sur commande, like “Hey Gay Paree Bop,” I sort of commanded myself into song. So in those, there are all kinds of points written where you can go off, do anything you like, but come back to them.

SL: Yeah. The more we do that, the freer it’s getting. And I imagine if we do it for a while, then somebody else’ll pick it up there and do it another way. And that’s got to be.

BG: I would certainly hope so. Because if we’re all going to space, what’s going to space with us will be music.

SL: Especially little tunes you can remember.

As a song lyricist, Brion Gysin worked on several projects. His most abiding collaboration was with soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy, whose sextet recorded the album Songs (1981). Lacy’s group also toured another set of Gysin songs as a ballet, Stuff, playing in France and Italy, but the music was never recorded: the lyrics were part of Gysin’s screenplay of Naked Lunch. Gysin did record his own solo album, performing most of those lyrics, Orgy Boys (1982). He already had sung on the Lacy record, with the bawdy “Luvzya,” in duet with drummer Oliver Johnson. Later, he recast some of his songs and wrote new ones with the guitarist Ramuntcho Matta. On a single they recorded “Junk” and “Kick That Habit,” among his original permutation poems, playing with trumpeter Don Cherry, plus a bassist and drummer. Then they recorded one side of an album under Gysin’s name (1985), performing in several Paris concerts (all of the Gysin/Matta collaborations were issued posthumously on CD as Gysin’s Self-Portrait Jumping). At the time, he liked to refer to himself as the oldest living rock star.

The following interview with Gysin and Lacy, on the occasion of their album, took place in May 1981.

Steve Lacy, you were setting painters’ texts to music and through that you found Brion. How did you know of him?

SL: I guess I knew he was a poet-painter.

BG: We met through Victor Herbert, and then again at the American Center in ‘73.

SL: In ‘65 in London, I had heard recordings—at that time they called it electronic poetry—and some of Brion’s stuff was on there.

His permutation poems?

BG: It must have been Henri Chopin’s record, OU.

SL: I thought it was amazing, I really liked it. I had been thinking in . . . not with electronics, but some of the results achieved.

Did that tie up with any jazz roots for you?

SL: Well, jazz is speech rhythms. It’s like parlando music. And it all comes from phraseology anyway, it’s just a language. So, when I heard that stuff, I found it exciting.

BG: My opinion is that Dizzy Gillespie hasn’t been recognized as a great sound poet.

SL: Absolutely. No question about it.

Your whole interest in that seems unique for a jazz musician.

SL: Well, you could find little snippets of that in many people, back to Louis Armstrong. You can think of Fats Waller and Billy Strayhorn and Ellington, and then to people like Red Allen and Roy Eldridge. Well, many. I think what I did was dig a certain vein a little bit wider or deeper than is customary, but it was nothing new on the scene really.

Brion Gysin, when did you first know of Steve Lacy?

BG: I’d heard his music and heard records, it must have been about ‘59 or ‘60. That was the moment jazz and poetry had suddenly arrived and been talked about in New York in 1959. There were a couple of efforts at this made by Gregory Corso and others. I didn’t think it worked at all. Then in Paris I met a group of poets called the Domaine Poétique. We had possibilities to do anything we wanted. That went on 1961-64.

What was your first collaboration?

SL: The first thing was “Dreams.” The music was written in ‘69, and I asked him to give me the lyrics in about ‘73 or ‘74. By that time I knew he was the inventor of the Dreamachine. And that really struck me. I had this piece called “Dreams,” and it was a melody that came to me in a dream in Rome. It was written to Italian lyrics by Falzoni, but it never got off the ground. But the melody was haunting. So I thought Brion, being an expert on dreams, might be able to supply me with the necessary lyrics, in English. And he agreed. He came up with the most fantastic thing, really, the lyrics are out of sight.

The music was what it is now?

SL: The melody was identical. But the bass line and some of the inner voices took a while to work out, quite a few years.

Brion, when did you first start noticing jazz?

BG: Oh, I always noticed it. I used to be very snooty about it too. I remember saying, “Well, it’s all very well, but they’re improvising on tunes that don’t interest me in the first place.” That’s where I stood, on the wrong side of the street. But I knew I was hearing both sides of the street.

Later, in Morocco, Paul Bowles and I were sharing an Arab house with a high tower where you could get very good reception. He had a good radio and we used to play nightlong games of listening to German jazz, Japanese jazz, Australian jazz, and all sorts of things you could get on short wave.

Also, in New York, Latouche did a rather disastrous show together with Duke Ellington, Twilight Alley. I went to Duke Ellington’s house and saw how that whole music machine worked.

Was there a musical imprint that you intended on your new record together, Songs? It seems on the edge of various styles. There are strains of Kurt Weill, for instance.

SL: Well, I’m aware of all these people and what they’ve done, and Weill was a big influence in my own work. But one thing that’s been a strong factor in this is my own desire to insert serious lyrics into the jazz fabric. It’s like a search for quality. To raise the level of the lyric, so you have something good to play on. Because we play with those words. When we play those tunes based on Brion’s words, all the music comes out of the words. I’ve been lucky to have Brion’s stuff to work with. For me it was a miracle finding stuff already made of that quality. Like when he gave me the words to “Dreams,” it came out perfect. Then I wanted to see what he had already done. He showed me this stuff and read it for me, and I thought it was great. Because it seemed like it was already set. Just the way he would read it, I could hear it in a certain way that it was already pitched. So I just had the fun part of mulling it over, listening to tapes of him reading it, and finally fixing the pitches and everything myself. And then to getting them realized is a long step and that involved, well, learning them.

BG: That’s right, I was just knocked out, in this photograph taken by Hart Leroy Bibbs during the recording session I’m just in a state of sheer ecstasy. And it’s because, when it was all put together like that with the sextet, I heard my own voice coming right through there in the whole thing.

How far back does the earliest song date from?

BG: Well, in the ‘40s, I had a project for making a musical out of the biography that I wrote of the man who was the original Uncle Tom, Josiah Henson (To Master, A Long Goodnight). And the only one from that period is “Nowhere Street.”

What had you written of that project?

BG: I wrote the story and the lyrics. The story was as it really happened, not the way Harriet Beecher Stowe saw it. In other words, how it led him on to all that and how he got kicked in the ass in the end by his name becoming the most pejorative one of all. He never thought this shit was going to fall on him like that. That was the way the musical was supposed to go. And “Nowhere Street” was . . . there’s a separation with his great love, he’s decided to make it north and she’s left in a kind of deserted town like Cincinnati, a suburb of Cincinnati in 1850, where “Nowhere Street” was. She comes on stage and the leaves are falling and lights are coming on in the houses and going off in others, mysterious, a kind of haunted house sort of thing, and frogs croaking.

How much of that did you see when setting the music?

SL: I never heard this part about Cincinnati before. But Bobby Few (piano player in Lacy’s group) is from Cincinnati.

BG: No shit!

SL: But it’s apparent in the lyrics. They’re so vivid in their painterly abilities that the whole thing is right there for you.

Do the Jajouka musicians of Morocco seem to be any point of contact between you?

SL: Yes. Brion hipped me to that whole thing—the music I’ve heard, meeting some of the people, and playing with the President. It’s been sort of a good glue between us, reinforcing other things. I’ve gotten into it as far as I could in the time. But it’s a trip. I would have to go there and give up everything else . . .

BG: Like me. Like I did.

SL: . . . And get to it. And I’m not about to do that.

BG: He’s scared.

SL: I’d like to go in a helicopter, stay for a few days and get out of there, you know, when I could.

BG: Like me. I stayed all the time there because of that.

SL: It would have been wild to hear Trane play with them. But maybe in another life or something, in another world.

When the two of you perform together, what establishes the time?

SL: Well, what we do is like when the songwriters do a demo of their tune. The lyricist sort of says it and the other guy sort of plays the melody, but shifting a little. So it’s not strict time. Sort of collapsed here and stretched out there, so it gives you an idea of how it might sound.

BG: Here’s the poor author standing in the crook of the piano.

SL: Like an art pauvre. No, sometimes it really comes out perfect, where it’s not exactly sung but heard. A kind of delivery.

BG: This is where you’re standing out there in front of twenty prospective backers and their girlfriends.

SL: Yeah, they got the singer next to them and the money in their pockets. “These guys wrote this song. Honey, you think you’d like to sing this? I’ll buy it for you.” . . . But where we usually do it is poetry festivals, where any kind of a musical phenomenon takes it out of the level of the ordinary there.

What is the role of improvisation between the two of you?

SL: In his work, I found it to be very jazz-like, in that he was living it. When he delivers it, he’s playing. It’s different each time. It’s delivered in a free, improvisational manner, and that leeway is written right into it.

BG: And things that I’ve written sur commande, like “Hey Gay Paree Bop,” I sort of commanded myself into song. So in those, there are all kinds of points written where you can go off, do anything you like, but come back to them.

SL: Yeah. The more we do that, the freer it’s getting. And I imagine if we do it for a while, then somebody else’ll pick it up there and do it another way. And that’s got to be.

BG: I would certainly hope so. Because if we’re all going to space, what’s going to space with us will be music.

SL: Especially little tunes you can remember.

III.

In late 1985 Gysin finished his second novel, The Last Museum, excerpts of which had been published in various literary reviews over the years. The book turned out quite different from what he originally imagined it would be, and in his last years was his main project. However, other books also appeared during that time. Once again, young friends and supporters brought this work to light. Terry Wilson’s book of interviews with Gysin, Here to Go (1982), was published by Re/Search Publications in San Francisco and subsequently by Quartet Books in London, who also reissued Gysin’s long out-of-print first novel. Légendes de Brion Gysin (1983), a short book of childhood memoirs with photos, came out in translation in France. Two older manuscripts were printed by Inkblot Press in California: Stories (1984), mostly written in Morocco in the 1950s, and Morocco Two (1986), his updated film script version of the Dietrich-Cooper classic. Also, in August, 1985, in barely a week, Gysin painted a last major work, the ten-canvas series called Calligraffiti of Fire, commissioned by the Academia Foundation.

The following interview took place over two afternoons nearly a year apart, in the fall of 1984 and the fall of 1985. During the interim, Gysin arrived at the final version of his novel by cutting it drastically. The excised bits were due to appear in a limited edition as Fault Lines.

Why did your new novel, The Last Museum, take you over fifteen years to write?

I wonder how I got it done so quickly, really. It was meant to last me a lifetime.

You went through two or three main periods of writing the book?

At least. One whole manuscript was submitted to my editor at Doubleday because I had signed my first contract with them in 1968. And they refused it. I remember the phrase my editor added, “What was Mr. Gysin thinking about, writing this?” I’d spent about a year writing that big, thick, woolly manuscript in Tangier.

The final version is the shortest, isn’t it?

Oh yeah, by far. The original version was tied to all the events of 1968 in Paris as well, which went quickly out of fashion. None of the novels written about that worked.

There was also a change before you reached the final version, I believe, from the third person to the first.

Yes, back and forth actually. But essentially the decision was made most recently to go right back to the same sort of first person that I had used in The Process, with many different voices, each one speaking in his or her own voice. Writing it in such a way that the voices actually sound back up off the page, that they stand out and are recognizable, without saying “he said,” “she said,” and that sort of thing. If there’s any confusion it just sounds like a crowd talking but with different tones of voice.

As all the things you do are interrelated, the way you describe it sounds like the effect of looking at your Moroccan marketplace paintings.

Yes, that’s absolutely true.

But it’s also connected to the aspect of flicker that one encounters with your Dreamachine.

As being a further dimension of human experience that isn’t usually referred to and that most people haven’t been in touch with, except momentarily in their lives. Because the Dreamachine is now available to anybody who can sit in front of one with eyes shut for a while and get to know more about himself, know more about vision. Vision isn’t just limited to seeing what’s out there, it also involves seeing what’s going on inside your own head.

The Dreamachine experience is very central to The Last Museum. It’s even more brought out here than in The Process. It’s faster, more intense, and moves more places. The flicker is quicker, in a sense.

Yes, I think so too. But I think very much of the Dreamachine as being an absolute watermark in the history of art. First of all, it’s the first object in the history of the world that you look at with your eyes closed. It’s much more like a religious experience in that sense. Which is what I thought immediately when I first had the flash of it riding in this car in the south of France in 1958.

How do you see that experience working in the fact of writing?

Well, in The Process it was really completely based on cannabis, on kif and smoking hash or grass at any rate, in Morocco, the whole scene, and the music of Jajouka high in the mountains. Everybody up there was on this sort of level of the emotion, the vibration of grass goes all the way through life there. So, in The Last Museum I’m putting it into a deeper region, that of death and after-death experience. I put it into a much more “spiritual” level, which is that of the flicker, the alpha band experience between eight and thirteen flickers a second. Hence all that interest in time too, and smaller and smaller increments of its measure.

Are all those terms such as pico- and femto-seconds real?

Oh absolutely, yes. Those are real entities with which modern science is dealing all the time now, within the last ten years.

The way it was tucked in there every now and then almost seemed like a joke.

Well, it is a joke to be dealing with fractions of seconds, with one three-hundredth of a second or whatever.

Each time they’re kind of tossed off like that, and then eventually they start coming back a little, getting larger.

First of all it’s to progress you down into the very low level where the trinto-seconds are now talked about, one to the minus thirtieth. They’re not much in use yet because that’s on the molecular level. Well, one could imagine a sesto-second, which is just a fraction of that, sixty zeros strung across the page, one to the minus sixtieth. These are obviously the areas in which we’re going to be working.

Virtually everything in this book is working that fast, in a way. All the regular preoccupations in a novel are brought along at that speed of consciousness.

The principle problem in the novel itself is time, time in which these events occur. I treated it one way in The Process, and I treated it in a much more advanced way in The Last Museum.

You set both books some time in the future. Why?

I’ve always been tempted to do that. For instance, The Process was predicated on the fact that the dollar had fallen, whereas in actual fact, the present state of the dollar now is much more likely to allow someone to buy the Sahara than it was then. Nevertheless, I put that book into the future at a time when any good full-blooded American thought the dollar could never fall.

The main importance of setting it then is an historical function.

Yes, but it’s also to set the reader’s mind at a place where he doesn’t quite expect it to be set. He knows that the mind-space, the time-space, is something that he has been used to reading as: I am, I was, I will be. Now it’s much more complex than just that. It circles around Present Time, the precise time you are reading it in.

The new book?

Yes. Both novels talk about Present Time a great deal. Present Time is the exact time in which you are completely concentrated on what you are reading. I mean, the words are slipping over the razor’s edge of the seconds as you read.

When did you come upon the Bardo Thodol structure of The Last Museum? Wasn’t the book at one point somewhat of a history of the Beat Hotel, or did the different elements come in at different times?

Now that I think of it, yes. The very first manuscript was really written very quickly, with the idea of satisfying Doubleday and getting out of the contract. Because they’d behaved so badly over The Process, they’d hated it and ordered it scrapped. I thought, My God, if I go through with this again. The new contract was signed and I was already getting a monthly allowance, I thought I better write just what comes off the top of my head and center it around 1968. I’d been in Paris in 1968 and so a lot of the things fell into place quite easily. I thought I’d write that kind of easy novel.

But what was there already in that first version?

Well, the hotel was always there, and it always had seven floors and seven rooms on each floor, like the days in the week for example. The forty-nine days of the Bardo Thodol of the Tibetan unreal estate firm.

Were both the Beat and the Bardo in your mind at that point?

I’ve forgotten, really. And that manuscript I destroyed, not too long ago as a matter of fact, it was completely superfluous. I abandoned it without rereading it even. I’ve done that often in my life. Shoals of manuscripts I’ve just . . . Burroughs too, I mean, really. The amount that he’s thrown away, just lost or forgotten or . . . The first book that I wrote, in the 1940s, has disappeared completely, called “Memoirs of a Mythomaniac.” Town and Country published two chapters of it, so that’s still available someplace. But all the rest of it is gone forever, as far as I know. There were three copies, I remember, and I destroyed only one. The other one was with an agent, who died I think. The third, where is it?

Was that book more autobiographical?

Yeah, it was détourné autobiography, more so than this.

Well, I see more autobiography in this book than in The Process.

Oh yeah, lots more. The Process had everything in it that I knew about Islam and Morocco, all the fun I had. That was partly because of Paul Bowles’ position in regard to Morocco, his monstrous Morocco, which I’ve only occasionally visited in the twenty-three years I lived there.

Did you use the cut-up much in The Last Museum?

Sure, absolutely. Also in The Process, long ago. But I smoothed them out so that they don’t look jagged anymore. Whereas William used them raw and it had an impressive force, sheer poetry with his own brand burned into it.

You make very special use of repetitions in this book, particularly you repeat facts and anecdotes. Is it like the same image seen coming back again?

That’s one part of it, yeah, and it trails everything else along with it as it comes. It pulls back that previous experience right up into the present again. And it’s very like my permutated poems, all the repetition with slight variants all the way as the same words turn over. On re-reading it recently, correcting the manuscript for the thousandth time, I thought that worked very well. First of all, it’s a bit of a surprise to anybody who’s reading it, “Oh, is this on purpose?” And then you say, “Yes, it is on purpose.” And it works through that. So, what I mean to do is for it to be happening in Present Time, the most Present Time possible situations, conversations as quick as a flash back and forth. Now you realize that several different levels of time are being suggested simultaneously.

Another device in the book that works similarly to the repetitions is when you write "(see illustration)" during certain passages.

It pulls up a picture, doesn’t it. First, you’re teased; then you’re a little annoyed; and then you start making your own. But the illustrations are there, I have them in my notebooks.

In the Tibetans’ Bardo there are seven floors. Why did you end your book at the fourth floor?

It ended itself at the fourth floor. From there on you are precipitated into an area of doubt, but with some knowledge of what is ahead upstairs. You know there’s an animal floor, and maybe a bird floor above that filled with holy ghosts, like the sacred pigeons on the very roof. But then again, as we don’t know the facts, maybe the roof blew off a long time ago. You can see how the underpinnings of Present Time have been torn out by the bottom floor having been ripped out, so that you’ve got the whole Bardo structure apparently suspended in mid-air. The floors below are disappearing up to that level, but then the others above do seem to exist.

And you hear possible news from upstairs. Did you take a lot of notes in relation to this novel?

Oh God, books and books and books, yearbooks of notes and clippings.

Are the place names in California true, as they spread out into Death Valley?

That’s all taken off the map. I went around by car to all those places in 1978, Apollo County and Mirage Lake.

You have a lot of fun with names in this book.

I’ve always enjoyed well-chosen names in literature. It’s an extra little pleasure to give people some amusement, the fact that you’re implying character by the sort of name you use, or your vision of that character. You’re letting them in on this private information which is a sort of joke.

You have a fondness for historical resonances, reminding us how some things haven’t changed nearly as much as we think.

I try to put things together in a place where you can see them. Like in the Middle Ages there were indeed outlandishly dressed guitar players with long hair and pointy shoes who were going around everywhere like hippies, and the fact that they’re out there today in front of the Pompidou Center, you start to say, “Ooh, wow.” A whole pinch of time is taken right under your fingers, you can just feel it. And when I say that they always had trouble with the students in May wine time, just at the time of their examinations, well you say, “Ooh, wow, that explains May 1968 and many another May.”

How strictly was the whole book mapped out?

Oh, very. To the millimeter, to the femtosecond. The Process too, The Process is a machine after all. I chose the persons of speech—I, thou, etcetera, I used them all—and then found out how they worked together, how they could talk to each other. A good deal of The Last Museum had to do with the geography of the hotel, it becomes clearer and clearer. Right from the very beginning, you should have moved from Room One to Two, Three, Four, but those rooms had already gone to the museum in California. That really kept guiding me all the time. The form that I had decided upon made it at the time a more stringent control but therefore all the easier. I believe in discipline. In my painting too, in everything I do, I always invent a problem, invent the rules for a game which doesn’t exist yet and then I do what I can except that I must keep to my own rules. I don’t go outside the square of the page or the canvas, or I do continually run out through all the edges but I make the rule and stick to it. It’s man as a maker of things. You have the right to do whatever you like with the material. Nobody can say no to that, can they?

But you have continued to make changes in The Last Museum, haven’t you?

Sometimes I can’t even say no to good advice from a publisher or two. Everyone told me my manuscript was too long, so I cut it. I cut about one hundred pages out of it, eventually. Some fifty short excerpts of that will be published with fifty illustrations by Keith Haring. They will be brought out as an art book with text and drawings on facing pages so that a really surprising tension is set up between the words and the pictures. I find it sensational and so will you, I think.

In late 1985 Gysin finished his second novel, The Last Museum, excerpts of which had been published in various literary reviews over the years. The book turned out quite different from what he originally imagined it would be, and in his last years was his main project. However, other books also appeared during that time. Once again, young friends and supporters brought this work to light. Terry Wilson’s book of interviews with Gysin, Here to Go (1982), was published by Re/Search Publications in San Francisco and subsequently by Quartet Books in London, who also reissued Gysin’s long out-of-print first novel. Légendes de Brion Gysin (1983), a short book of childhood memoirs with photos, came out in translation in France. Two older manuscripts were printed by Inkblot Press in California: Stories (1984), mostly written in Morocco in the 1950s, and Morocco Two (1986), his updated film script version of the Dietrich-Cooper classic. Also, in August, 1985, in barely a week, Gysin painted a last major work, the ten-canvas series called Calligraffiti of Fire, commissioned by the Academia Foundation.

The following interview took place over two afternoons nearly a year apart, in the fall of 1984 and the fall of 1985. During the interim, Gysin arrived at the final version of his novel by cutting it drastically. The excised bits were due to appear in a limited edition as Fault Lines.

Why did your new novel, The Last Museum, take you over fifteen years to write?

I wonder how I got it done so quickly, really. It was meant to last me a lifetime.

You went through two or three main periods of writing the book?

At least. One whole manuscript was submitted to my editor at Doubleday because I had signed my first contract with them in 1968. And they refused it. I remember the phrase my editor added, “What was Mr. Gysin thinking about, writing this?” I’d spent about a year writing that big, thick, woolly manuscript in Tangier.

The final version is the shortest, isn’t it?

Oh yeah, by far. The original version was tied to all the events of 1968 in Paris as well, which went quickly out of fashion. None of the novels written about that worked.

There was also a change before you reached the final version, I believe, from the third person to the first.

Yes, back and forth actually. But essentially the decision was made most recently to go right back to the same sort of first person that I had used in The Process, with many different voices, each one speaking in his or her own voice. Writing it in such a way that the voices actually sound back up off the page, that they stand out and are recognizable, without saying “he said,” “she said,” and that sort of thing. If there’s any confusion it just sounds like a crowd talking but with different tones of voice.

As all the things you do are interrelated, the way you describe it sounds like the effect of looking at your Moroccan marketplace paintings.

Yes, that’s absolutely true.

But it’s also connected to the aspect of flicker that one encounters with your Dreamachine.

As being a further dimension of human experience that isn’t usually referred to and that most people haven’t been in touch with, except momentarily in their lives. Because the Dreamachine is now available to anybody who can sit in front of one with eyes shut for a while and get to know more about himself, know more about vision. Vision isn’t just limited to seeing what’s out there, it also involves seeing what’s going on inside your own head.

The Dreamachine experience is very central to The Last Museum. It’s even more brought out here than in The Process. It’s faster, more intense, and moves more places. The flicker is quicker, in a sense.

Yes, I think so too. But I think very much of the Dreamachine as being an absolute watermark in the history of art. First of all, it’s the first object in the history of the world that you look at with your eyes closed. It’s much more like a religious experience in that sense. Which is what I thought immediately when I first had the flash of it riding in this car in the south of France in 1958.

How do you see that experience working in the fact of writing?

Well, in The Process it was really completely based on cannabis, on kif and smoking hash or grass at any rate, in Morocco, the whole scene, and the music of Jajouka high in the mountains. Everybody up there was on this sort of level of the emotion, the vibration of grass goes all the way through life there. So, in The Last Museum I’m putting it into a deeper region, that of death and after-death experience. I put it into a much more “spiritual” level, which is that of the flicker, the alpha band experience between eight and thirteen flickers a second. Hence all that interest in time too, and smaller and smaller increments of its measure.

Are all those terms such as pico- and femto-seconds real?

Oh absolutely, yes. Those are real entities with which modern science is dealing all the time now, within the last ten years.

The way it was tucked in there every now and then almost seemed like a joke.

Well, it is a joke to be dealing with fractions of seconds, with one three-hundredth of a second or whatever.

Each time they’re kind of tossed off like that, and then eventually they start coming back a little, getting larger.

First of all it’s to progress you down into the very low level where the trinto-seconds are now talked about, one to the minus thirtieth. They’re not much in use yet because that’s on the molecular level. Well, one could imagine a sesto-second, which is just a fraction of that, sixty zeros strung across the page, one to the minus sixtieth. These are obviously the areas in which we’re going to be working.

Virtually everything in this book is working that fast, in a way. All the regular preoccupations in a novel are brought along at that speed of consciousness.

The principle problem in the novel itself is time, time in which these events occur. I treated it one way in The Process, and I treated it in a much more advanced way in The Last Museum.

You set both books some time in the future. Why?

I’ve always been tempted to do that. For instance, The Process was predicated on the fact that the dollar had fallen, whereas in actual fact, the present state of the dollar now is much more likely to allow someone to buy the Sahara than it was then. Nevertheless, I put that book into the future at a time when any good full-blooded American thought the dollar could never fall.

The main importance of setting it then is an historical function.

Yes, but it’s also to set the reader’s mind at a place where he doesn’t quite expect it to be set. He knows that the mind-space, the time-space, is something that he has been used to reading as: I am, I was, I will be. Now it’s much more complex than just that. It circles around Present Time, the precise time you are reading it in.

The new book?

Yes. Both novels talk about Present Time a great deal. Present Time is the exact time in which you are completely concentrated on what you are reading. I mean, the words are slipping over the razor’s edge of the seconds as you read.

When did you come upon the Bardo Thodol structure of The Last Museum? Wasn’t the book at one point somewhat of a history of the Beat Hotel, or did the different elements come in at different times?

Now that I think of it, yes. The very first manuscript was really written very quickly, with the idea of satisfying Doubleday and getting out of the contract. Because they’d behaved so badly over The Process, they’d hated it and ordered it scrapped. I thought, My God, if I go through with this again. The new contract was signed and I was already getting a monthly allowance, I thought I better write just what comes off the top of my head and center it around 1968. I’d been in Paris in 1968 and so a lot of the things fell into place quite easily. I thought I’d write that kind of easy novel.

But what was there already in that first version?

Well, the hotel was always there, and it always had seven floors and seven rooms on each floor, like the days in the week for example. The forty-nine days of the Bardo Thodol of the Tibetan unreal estate firm.

Were both the Beat and the Bardo in your mind at that point?

I’ve forgotten, really. And that manuscript I destroyed, not too long ago as a matter of fact, it was completely superfluous. I abandoned it without rereading it even. I’ve done that often in my life. Shoals of manuscripts I’ve just . . . Burroughs too, I mean, really. The amount that he’s thrown away, just lost or forgotten or . . . The first book that I wrote, in the 1940s, has disappeared completely, called “Memoirs of a Mythomaniac.” Town and Country published two chapters of it, so that’s still available someplace. But all the rest of it is gone forever, as far as I know. There were three copies, I remember, and I destroyed only one. The other one was with an agent, who died I think. The third, where is it?

Was that book more autobiographical?

Yeah, it was détourné autobiography, more so than this.

Well, I see more autobiography in this book than in The Process.

Oh yeah, lots more. The Process had everything in it that I knew about Islam and Morocco, all the fun I had. That was partly because of Paul Bowles’ position in regard to Morocco, his monstrous Morocco, which I’ve only occasionally visited in the twenty-three years I lived there.

Did you use the cut-up much in The Last Museum?

Sure, absolutely. Also in The Process, long ago. But I smoothed them out so that they don’t look jagged anymore. Whereas William used them raw and it had an impressive force, sheer poetry with his own brand burned into it.

You make very special use of repetitions in this book, particularly you repeat facts and anecdotes. Is it like the same image seen coming back again?

That’s one part of it, yeah, and it trails everything else along with it as it comes. It pulls back that previous experience right up into the present again. And it’s very like my permutated poems, all the repetition with slight variants all the way as the same words turn over. On re-reading it recently, correcting the manuscript for the thousandth time, I thought that worked very well. First of all, it’s a bit of a surprise to anybody who’s reading it, “Oh, is this on purpose?” And then you say, “Yes, it is on purpose.” And it works through that. So, what I mean to do is for it to be happening in Present Time, the most Present Time possible situations, conversations as quick as a flash back and forth. Now you realize that several different levels of time are being suggested simultaneously.

Another device in the book that works similarly to the repetitions is when you write "(see illustration)" during certain passages.

It pulls up a picture, doesn’t it. First, you’re teased; then you’re a little annoyed; and then you start making your own. But the illustrations are there, I have them in my notebooks.

In the Tibetans’ Bardo there are seven floors. Why did you end your book at the fourth floor?