Axolotl: The Adventure of Free Music

published in Passion (Paris), Apr. 29-May 12, 1982

To follow their music, you might need a map. Luckily, there is none. The sounds are so sensual, they turn music on its ear. They are Axolotl, a Nahuatl word meaning the water spirit.

“This music evolves very quickly,” says Jacques Oger, tenor and baritone saxophonist in this young French trio. “We have to change, to continue searching for new things. We want to make music that uses sounds people aren’t accustomed to hearing, to build an improvised music created by the instant.”

Jazz is the closest probable label to identify their general instrumentation of two horns and a guitar, and their oblique ways of playing them. Their language is more one of sounds than of notes. Acoustic and electric guitarist Marc Dufourd, Etienne Brunet on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, and Oger, play an ever-expanding bag of miscellaneous instruments that include amplified sandpaper, ping-pong balls bouncing on piano strings, an amplified bucket of water sloshing around, a ringful of keys falling, and lots of etcetera. But these are not at all like sound effects; rather, they are played like instruments, given rhythm and timbre. According to the contours of the moment, the musicians may play their horns with the wrong mouthpieces, may play them like shovels or helicopters or canoes or snow, or they may go electric, with Dufourd’s electronic devices and Oger’s stylophone, though never using tapes or overdubbing.

“The more people listen to very different kinds of music---to Varèse, ethnic music, the Sex Pistols, and so on---the more they may care to have an interest in improvised music,” suggests Dufourd. Certainly their own tastes span the entire panorama of music, though they insist on claiming no allegiances to any particular form.

The music of Axolotl is the proverbial room in your house that you never knew existed: each step you take inside, the larger it becomes. And it is never the same. The intuition in their playing generates a music on the edge of being, the three voices seamlessly welded into a single thing that, whatever it is, seems right and is uncompromisingly alive.

The public response to their music is itself a paradox. “When we play in Paris,” says Oger, “in small clubs who do some publicity there are 50 people maximum. But when we play in the provinces with hardly any publicity, and at festivals, where lots of people have certainly never heard this sort of music, right away there’s 1,000 people and we’re received very, very well.

“This music has all the appearances of aggressivity, which is very rare these days, though it’s not against people. It’s simply a material of sounds that must make the ears react, because jazz today, save for a few exceptions, provokes no reactions anymore. People like what we do because there are sounds that surprise them.”

The group has learned by experience that it’s the promoters who fear the risk and adventure of free music, and not the public. But why Parisians, too, would shy away from Axolotl’s music is incomprehensible to Oger. “In spite of everything in Paris, there’s still a base of the intelligentsia that’s interested in the literature of the avant garde, the painting, the theater, the cinema. But no one’s interested in the music of the avant garde.”

Such treatment by sophisticated, if vogue-minded, Parisian audiences is nothing new, the group feels. As Denis Constant explains in his forthcoming book, Histoire du Jazz en France, “the arrival of free jazz (in the mid-1960s) in France was a determining factor in the evolution” of the music of the new, and mostly young, French jazz musicians. But, the musicians of Axolotl contend, the audiences were sooner interested in the black power revolutionary politics of the American musicians here in the late 1960s and early ‘70s---Archie Shepp, the drummer Sunny Murray, the Art Ensemble of Chicago---but did not listen to the same music at home for more than five minutes. “They were looking at the color,” Brunet charges, though of course American audiences didn’t want to look at even that.

With Paris especially politicized in those years, the French free jazz musicians tended to get eclipsed. For instance, there was never a single record company to consolidate their efforts, as there have been in other countries. Musicians sensed this lack of public support for free improvisational music and look its lessons in other directions. Thus, when Axolotl was formed three years ago, it was a little like a mutant in a terrain of easy listeners (which is not to deny that a number of important French innovators have continued working with improvised music).

Being above all a collective, the group has very precise ways of working together. Individually, according to Oger, they investigate ways of playing rhythms that correspond to “a climate of excessiveness, as much in energy as in calm, in sonority as in silence.” As a group, they work toward a sort of traffic of complementary sounds, seeking “an extreme rapidity in the reactions, in each others’ responses.” The things they know, he says, “we prefer to forget a little, so that they can come back to us again as surprises.”

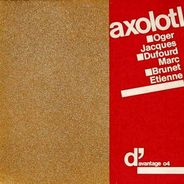

Recording a highly combustible album last year for the musician-produced label D’Avantage, which has issued several albums by the startling and unpredictable trumpeter-trombonist Jacques Berrocal, Axolotl sought a sound closer to contemporary music than free jazz. The improvisations on the record are “more about compression,” says Dufourd, “more about the attack than the cry,” the latter being more indicative of the early years of free jazz. Even the album’s cover provokes: a sheet of medium-grade sandpaper.

How did they arrive at this music? “These are things that happen to you just like that,” says Oger, “practically overnight. You don’t know why. And in fact, you must follow it.”

* * *

Subsequently, expanded to a quintet, Axolotl released a second album in 1983, Outmanoeuvre, and eventually disbanded. They can be seen here in a brief performance at the Paris club Le Dunois, as well as in this 1984 video.

Etienne Brunet still works playing improvised music.

And while no longer active as a musician, Jacques Oger founded the independent label devoted to improvised music in France, Potlatch.

Souffle Continu Records reissued Axolotl's first record, Abrasive (picture above), on vinyl in 2023.

published in Passion (Paris), Apr. 29-May 12, 1982

To follow their music, you might need a map. Luckily, there is none. The sounds are so sensual, they turn music on its ear. They are Axolotl, a Nahuatl word meaning the water spirit.

“This music evolves very quickly,” says Jacques Oger, tenor and baritone saxophonist in this young French trio. “We have to change, to continue searching for new things. We want to make music that uses sounds people aren’t accustomed to hearing, to build an improvised music created by the instant.”

Jazz is the closest probable label to identify their general instrumentation of two horns and a guitar, and their oblique ways of playing them. Their language is more one of sounds than of notes. Acoustic and electric guitarist Marc Dufourd, Etienne Brunet on alto saxophone and bass clarinet, and Oger, play an ever-expanding bag of miscellaneous instruments that include amplified sandpaper, ping-pong balls bouncing on piano strings, an amplified bucket of water sloshing around, a ringful of keys falling, and lots of etcetera. But these are not at all like sound effects; rather, they are played like instruments, given rhythm and timbre. According to the contours of the moment, the musicians may play their horns with the wrong mouthpieces, may play them like shovels or helicopters or canoes or snow, or they may go electric, with Dufourd’s electronic devices and Oger’s stylophone, though never using tapes or overdubbing.

“The more people listen to very different kinds of music---to Varèse, ethnic music, the Sex Pistols, and so on---the more they may care to have an interest in improvised music,” suggests Dufourd. Certainly their own tastes span the entire panorama of music, though they insist on claiming no allegiances to any particular form.

The music of Axolotl is the proverbial room in your house that you never knew existed: each step you take inside, the larger it becomes. And it is never the same. The intuition in their playing generates a music on the edge of being, the three voices seamlessly welded into a single thing that, whatever it is, seems right and is uncompromisingly alive.

The public response to their music is itself a paradox. “When we play in Paris,” says Oger, “in small clubs who do some publicity there are 50 people maximum. But when we play in the provinces with hardly any publicity, and at festivals, where lots of people have certainly never heard this sort of music, right away there’s 1,000 people and we’re received very, very well.

“This music has all the appearances of aggressivity, which is very rare these days, though it’s not against people. It’s simply a material of sounds that must make the ears react, because jazz today, save for a few exceptions, provokes no reactions anymore. People like what we do because there are sounds that surprise them.”

The group has learned by experience that it’s the promoters who fear the risk and adventure of free music, and not the public. But why Parisians, too, would shy away from Axolotl’s music is incomprehensible to Oger. “In spite of everything in Paris, there’s still a base of the intelligentsia that’s interested in the literature of the avant garde, the painting, the theater, the cinema. But no one’s interested in the music of the avant garde.”

Such treatment by sophisticated, if vogue-minded, Parisian audiences is nothing new, the group feels. As Denis Constant explains in his forthcoming book, Histoire du Jazz en France, “the arrival of free jazz (in the mid-1960s) in France was a determining factor in the evolution” of the music of the new, and mostly young, French jazz musicians. But, the musicians of Axolotl contend, the audiences were sooner interested in the black power revolutionary politics of the American musicians here in the late 1960s and early ‘70s---Archie Shepp, the drummer Sunny Murray, the Art Ensemble of Chicago---but did not listen to the same music at home for more than five minutes. “They were looking at the color,” Brunet charges, though of course American audiences didn’t want to look at even that.

With Paris especially politicized in those years, the French free jazz musicians tended to get eclipsed. For instance, there was never a single record company to consolidate their efforts, as there have been in other countries. Musicians sensed this lack of public support for free improvisational music and look its lessons in other directions. Thus, when Axolotl was formed three years ago, it was a little like a mutant in a terrain of easy listeners (which is not to deny that a number of important French innovators have continued working with improvised music).

Being above all a collective, the group has very precise ways of working together. Individually, according to Oger, they investigate ways of playing rhythms that correspond to “a climate of excessiveness, as much in energy as in calm, in sonority as in silence.” As a group, they work toward a sort of traffic of complementary sounds, seeking “an extreme rapidity in the reactions, in each others’ responses.” The things they know, he says, “we prefer to forget a little, so that they can come back to us again as surprises.”

Recording a highly combustible album last year for the musician-produced label D’Avantage, which has issued several albums by the startling and unpredictable trumpeter-trombonist Jacques Berrocal, Axolotl sought a sound closer to contemporary music than free jazz. The improvisations on the record are “more about compression,” says Dufourd, “more about the attack than the cry,” the latter being more indicative of the early years of free jazz. Even the album’s cover provokes: a sheet of medium-grade sandpaper.

How did they arrive at this music? “These are things that happen to you just like that,” says Oger, “practically overnight. You don’t know why. And in fact, you must follow it.”

* * *

Subsequently, expanded to a quintet, Axolotl released a second album in 1983, Outmanoeuvre, and eventually disbanded. They can be seen here in a brief performance at the Paris club Le Dunois, as well as in this 1984 video.

Etienne Brunet still works playing improvised music.

And while no longer active as a musician, Jacques Oger founded the independent label devoted to improvised music in France, Potlatch.

Souffle Continu Records reissued Axolotl's first record, Abrasive (picture above), on vinyl in 2023.