The American Center Breathes New Life

published in Passion (Paris), Dec. 10-23, 1981

Despite its modest beginnings 50 years ago, the American Center has blossomed into one of the leading institutions of cultural exchange in Paris and a major forum for the avant-garde. Situated at 261 Boulevard Raspail in the 14th arrondissement, it has the appearance of a small liberal arts college, looming brightly beyond its walled garden next to Montparnasse.

It was founded in 1931 by the American Episcopalian congregation of Paris to keep young Americans away from the evil influences of Paris cafés. From the pages of the Ivy League, it offered all that the more chaste and respectable could hope to occupy themselves with: billiard room, lounge, library, swimming pool, gymnasium, restaurant, theater, tea-time, and dances.

Yet, in weathering the last 20 years, “it has become the experimental free space that was lacking in Paris,” says Jean-Jacques Lebel, whose first Festival of Free Expression in 1964 marked the center’s initial great leap forward.

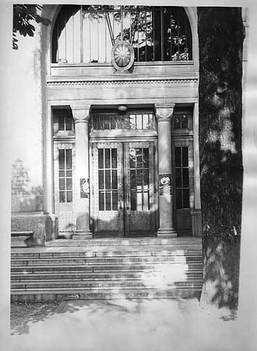

The founders leased 5,000 square meters of prime Montparnasse land from the Archbishopric of Paris, promising to preserve the century-old cedar of Lebanon planted by the Vicomte de Chateaubriand, whose estate had included the property. The roots of the towering tree, a benevolent guard at the center’s doors, were promptly encased in a masonry vault when Welles Bosworth, the American architect who also renovated the Palace of Versailles, designed the building.

During the last war, the property was occupied in turn by French, German, and American armies, before the city officially returned it. From 1948 through 1950, it functioned as the American Community School.

The center’s social and religious functions churned on through the sedate 1950s. In the early ‘60s, however, Jack Egle, director of the Council on International Educational Exchange, was chosen as the new chairman of the board of directors. He opened the center’s membership to all nationalities and not surprisingly the center’s cultural activities began to expand. David Davis, named director in 1963, was the one who, innocently enough, gave the go-ahead to Lebel to produce his Festival of Free Expression.

The Festival ran for a week in May and included jazz by Johnny Griffin, films by Man Ray and Henri Michaux, happenings by Ben and by Carolee Schneemann—with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp looking on—and an exhibit of paintings by such artists as Andy Warhol, Christo, Roy Lichtenstein, and Valerio Adami. Put mildly, the center had never seen anything like it.

A year later, Lebel showed the first Warhol film in Europe, the eight-hour Sleep, and in 1966 he directed Picasso’s play Le Désir attrapé par la queue under a circus tent at the center, with Rita Renoir, Taylor Mead, and Ultra Violet, and the Soft Machine doing the music. Picasso and Max Ernst attended. Lebel also brought in the first concert by Fluxus, the artists’ collective with Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Vostel, and others.

“It all came from this contestation interne, this fire of renewal from the inside,” says Lebel. “We invented a cultural movement which was multi-lingual and international.” “We created pieces according to the spaces we had,” adds Lebel, who today works as a journalist and organizes an international poetry festival. “We did a happening in the swimming pool; everybody was naked. Alejandro Jodorowsky did one where he cut the heads off chickens and there was blood all over the place. The Living Theatre, who were artists in residence for a year, did mysteries and smaller pieces there.”

How was it all possible? “The board of directors went to bed early and we’d pay off the concierge with wine. There was no violence, we were just having fun.” Lebel’s only regret is the loss of the swimming pool, covered over for a dance studio in the early 1970s.

As the likes of Hemingway and Malraux had frequented the center in earlier years, so now did André Breton, Octavio Paz, Samuel Beckett, Jacques Lacan. And it was high time the center became an active part of local history: Apollinaire and Mondrian had worked across the street, Picasso down a block, up a few blocks stand Rodin’s imposing sculpture of Balzac and a version of Brancusi’s The Kiss, plus the fertile Montparnasse cafés.

In 1967, Henry Pillsbury, a young graduate of Yale and Berkeley with a Ph.D. in French began to visit the center. “I’m a classic center graduate,” says Pillsbury, 44, now the executive director. “I went there and found myself, and got into theater there.” Soon he was acting in and directing works by many of the new provocative American playwrights at the center: Sam Shepard, Megan Terry, Israel Horovitz, Ed Bullins.

Pillsbury was asked to be the temporary director in late 1969, after the death of David Davis; “temporary,” in those chaotic years, turned out to mean three years, after which he left the center and devoted himself exclusively to theater in Paris until resuming the post in 1979. Yet it was a highly active time: “We would have six or seven events going on simultaneously in that building on a given night,” Pillsbury recalls, “and then we had it all over the Montparnasse area.”

It was a great period for jazz as well, despite complaints from the neighboring maternity ward, with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Archie Shepp, Sun Ra, and others often playing at the center. “Anthony Braxton was more or less a permanent fixture there during a year and a half. We had a very good electronic music studio—which isn’t there anymore—where Braxton first got interested in electronic music,” says Pillsbury.

In the wake of May 1968, the center was often at the mercy of young political power-brokers; every possible group, notably the Black Panthers, laid claim to the throne. “It was the heyday of the cheap charter flights,” Pillsbury explains. “There was a lot of hanging out in the lounge and restaurant, it was hard to control.”

Despite the turmoil, though, the center was never closed nor occupied. “It went through that evolution and came out swimming faster than almost any comparable institution in France that had the same kind of ferment,” says Pillsbury. “Within ten years it went through a whole upheaval and came out with a new definition of itself. The center is not a building, it’s a neighborhood.”

In the mid-1970s, Jacques Burnier, a karate instructor who spoke no English, was brought in as director to clean up the place. But it was not until Judith Pisar arrived on the scene in 1976 that the center took wings. “I saw that there was potential there,” she says, “something marvelous could happen with it.”

Pisar wasn’t new to arts administration. She had formerly produced a lecture series in New York called “The Composer Speaks,” worked as Merce Cunningham’s manager, and then become director of music at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Immediately, she put her connections to work.

An old friend now at the Rockefeller Foundation offered a $10,000 matching grant. Merce Cunningham and John Cage came to perform in a fund-raising gala and gave workshops; the result was Cage’s famous plants music concert, “Branches,” in 1978 (Burnier, outdone, had conga drummers competing upstairs). Suddenly, fully independent of government support, the center gained credibility among the public and the press. Next, Pisar raised $150,000 by writing to everyone she knew. Howard Klein, at the Rockefeller Foundation, came back with another small grant and soon negotiated a major three-year grant of $375,000.

Pisar, as chairman of the board, brought back Pillsbury, as well as Alexander Mehdevi—a Mexican-born Persian-American writer of four children’s books and director of New York’s Rizzoli International Bookstore and Gallery—and video arts specialist Don Foresta, formerly director of the American Embassy’s Cultural Center on Rue du Dragon. A solid team of non-bureaucrat arts professionals, one of their decisions was to hire architect Hugh Hardy to recycle the building for its present uses and to draw up the list of further repairs needed as funds become available. Pisar is the first to point out that the center still needs a couple of million dollars of work.

Pillsbury, Pisar, and Foresta engineered full-scale programs of theater, music, visual arts, and dance, in performance and workshop, with the likes of Xenakis, Foss, Mabou Mines, Helmut Newton, Joe Chaikin, Phil Glass, Solaris, Douglas Dunn, and Trisha Brown. Lebel came back to organize the annual international poetry festival Polyphonix, which has included Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and to teach a course in “multi-lingual creative processes.”

Though the center has become known for its innovative and near-exhaustive programming, it is Mehdevi who has had to make it work. By the end of the year he expects membership to surpass 8,500, of which the majority is French. The diverse and carefully balanced program of classes contributes 83% of the 1981 budget of $5.7 million. Some 2,500 members alone, comprising 65 nationalities, are enrolled in the popular American English classes; the arts courses cover all the media, with 22 classes in dance.

“Our members are mostly young people living in the city, looking for something to do that is active,” says Mehdevi. “They are interested and at the same time want to mix a certain active joyfulness with learning, with some aspects of research.” Presently the center brings about 150 artists a year from abroad.

“The center has put itself absolutely at the heart of the Parisian process of artists meeting each other,” says Pillsbury.

How American is the center? “Very,” says Pillsbury. “It’s very pragmatic, very empirical—‘let’s try it and see.’ The founders had the money, they found good land, they made a nice building.”

As Jack Lang, the French minister of culture, told Pisar: “You know, we all have a lot to learn from you. You are the model example of what a cultural institution should be.”

* * * *

Coda: Throughout the 1980s, the American Center became so active that its directors began to have greater ambitions for the institution. Late in the decade, faced with a building in need of serious repairs, they went into contract with the city of Paris for a lot in the Bercy district and hired architect Frank Gehry to design a grand new building. The reborn American Center finally opened in 1994, but between its hefty price tag, a substantial operating budget, and accumulated debt, the building was put up for sale less than two years later. The state eventually bought the building and, after extensive renovations, at last in 2005 it became the thriving new home of the Cinémathèque Française.

published in Passion (Paris), Dec. 10-23, 1981

Despite its modest beginnings 50 years ago, the American Center has blossomed into one of the leading institutions of cultural exchange in Paris and a major forum for the avant-garde. Situated at 261 Boulevard Raspail in the 14th arrondissement, it has the appearance of a small liberal arts college, looming brightly beyond its walled garden next to Montparnasse.

It was founded in 1931 by the American Episcopalian congregation of Paris to keep young Americans away from the evil influences of Paris cafés. From the pages of the Ivy League, it offered all that the more chaste and respectable could hope to occupy themselves with: billiard room, lounge, library, swimming pool, gymnasium, restaurant, theater, tea-time, and dances.

Yet, in weathering the last 20 years, “it has become the experimental free space that was lacking in Paris,” says Jean-Jacques Lebel, whose first Festival of Free Expression in 1964 marked the center’s initial great leap forward.

The founders leased 5,000 square meters of prime Montparnasse land from the Archbishopric of Paris, promising to preserve the century-old cedar of Lebanon planted by the Vicomte de Chateaubriand, whose estate had included the property. The roots of the towering tree, a benevolent guard at the center’s doors, were promptly encased in a masonry vault when Welles Bosworth, the American architect who also renovated the Palace of Versailles, designed the building.

During the last war, the property was occupied in turn by French, German, and American armies, before the city officially returned it. From 1948 through 1950, it functioned as the American Community School.

The center’s social and religious functions churned on through the sedate 1950s. In the early ‘60s, however, Jack Egle, director of the Council on International Educational Exchange, was chosen as the new chairman of the board of directors. He opened the center’s membership to all nationalities and not surprisingly the center’s cultural activities began to expand. David Davis, named director in 1963, was the one who, innocently enough, gave the go-ahead to Lebel to produce his Festival of Free Expression.

The Festival ran for a week in May and included jazz by Johnny Griffin, films by Man Ray and Henri Michaux, happenings by Ben and by Carolee Schneemann—with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp looking on—and an exhibit of paintings by such artists as Andy Warhol, Christo, Roy Lichtenstein, and Valerio Adami. Put mildly, the center had never seen anything like it.

A year later, Lebel showed the first Warhol film in Europe, the eight-hour Sleep, and in 1966 he directed Picasso’s play Le Désir attrapé par la queue under a circus tent at the center, with Rita Renoir, Taylor Mead, and Ultra Violet, and the Soft Machine doing the music. Picasso and Max Ernst attended. Lebel also brought in the first concert by Fluxus, the artists’ collective with Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Vostel, and others.

“It all came from this contestation interne, this fire of renewal from the inside,” says Lebel. “We invented a cultural movement which was multi-lingual and international.” “We created pieces according to the spaces we had,” adds Lebel, who today works as a journalist and organizes an international poetry festival. “We did a happening in the swimming pool; everybody was naked. Alejandro Jodorowsky did one where he cut the heads off chickens and there was blood all over the place. The Living Theatre, who were artists in residence for a year, did mysteries and smaller pieces there.”

How was it all possible? “The board of directors went to bed early and we’d pay off the concierge with wine. There was no violence, we were just having fun.” Lebel’s only regret is the loss of the swimming pool, covered over for a dance studio in the early 1970s.

As the likes of Hemingway and Malraux had frequented the center in earlier years, so now did André Breton, Octavio Paz, Samuel Beckett, Jacques Lacan. And it was high time the center became an active part of local history: Apollinaire and Mondrian had worked across the street, Picasso down a block, up a few blocks stand Rodin’s imposing sculpture of Balzac and a version of Brancusi’s The Kiss, plus the fertile Montparnasse cafés.

In 1967, Henry Pillsbury, a young graduate of Yale and Berkeley with a Ph.D. in French began to visit the center. “I’m a classic center graduate,” says Pillsbury, 44, now the executive director. “I went there and found myself, and got into theater there.” Soon he was acting in and directing works by many of the new provocative American playwrights at the center: Sam Shepard, Megan Terry, Israel Horovitz, Ed Bullins.

Pillsbury was asked to be the temporary director in late 1969, after the death of David Davis; “temporary,” in those chaotic years, turned out to mean three years, after which he left the center and devoted himself exclusively to theater in Paris until resuming the post in 1979. Yet it was a highly active time: “We would have six or seven events going on simultaneously in that building on a given night,” Pillsbury recalls, “and then we had it all over the Montparnasse area.”

It was a great period for jazz as well, despite complaints from the neighboring maternity ward, with the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Archie Shepp, Sun Ra, and others often playing at the center. “Anthony Braxton was more or less a permanent fixture there during a year and a half. We had a very good electronic music studio—which isn’t there anymore—where Braxton first got interested in electronic music,” says Pillsbury.

In the wake of May 1968, the center was often at the mercy of young political power-brokers; every possible group, notably the Black Panthers, laid claim to the throne. “It was the heyday of the cheap charter flights,” Pillsbury explains. “There was a lot of hanging out in the lounge and restaurant, it was hard to control.”

Despite the turmoil, though, the center was never closed nor occupied. “It went through that evolution and came out swimming faster than almost any comparable institution in France that had the same kind of ferment,” says Pillsbury. “Within ten years it went through a whole upheaval and came out with a new definition of itself. The center is not a building, it’s a neighborhood.”

In the mid-1970s, Jacques Burnier, a karate instructor who spoke no English, was brought in as director to clean up the place. But it was not until Judith Pisar arrived on the scene in 1976 that the center took wings. “I saw that there was potential there,” she says, “something marvelous could happen with it.”

Pisar wasn’t new to arts administration. She had formerly produced a lecture series in New York called “The Composer Speaks,” worked as Merce Cunningham’s manager, and then become director of music at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Immediately, she put her connections to work.

An old friend now at the Rockefeller Foundation offered a $10,000 matching grant. Merce Cunningham and John Cage came to perform in a fund-raising gala and gave workshops; the result was Cage’s famous plants music concert, “Branches,” in 1978 (Burnier, outdone, had conga drummers competing upstairs). Suddenly, fully independent of government support, the center gained credibility among the public and the press. Next, Pisar raised $150,000 by writing to everyone she knew. Howard Klein, at the Rockefeller Foundation, came back with another small grant and soon negotiated a major three-year grant of $375,000.

Pisar, as chairman of the board, brought back Pillsbury, as well as Alexander Mehdevi—a Mexican-born Persian-American writer of four children’s books and director of New York’s Rizzoli International Bookstore and Gallery—and video arts specialist Don Foresta, formerly director of the American Embassy’s Cultural Center on Rue du Dragon. A solid team of non-bureaucrat arts professionals, one of their decisions was to hire architect Hugh Hardy to recycle the building for its present uses and to draw up the list of further repairs needed as funds become available. Pisar is the first to point out that the center still needs a couple of million dollars of work.

Pillsbury, Pisar, and Foresta engineered full-scale programs of theater, music, visual arts, and dance, in performance and workshop, with the likes of Xenakis, Foss, Mabou Mines, Helmut Newton, Joe Chaikin, Phil Glass, Solaris, Douglas Dunn, and Trisha Brown. Lebel came back to organize the annual international poetry festival Polyphonix, which has included Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and to teach a course in “multi-lingual creative processes.”

Though the center has become known for its innovative and near-exhaustive programming, it is Mehdevi who has had to make it work. By the end of the year he expects membership to surpass 8,500, of which the majority is French. The diverse and carefully balanced program of classes contributes 83% of the 1981 budget of $5.7 million. Some 2,500 members alone, comprising 65 nationalities, are enrolled in the popular American English classes; the arts courses cover all the media, with 22 classes in dance.

“Our members are mostly young people living in the city, looking for something to do that is active,” says Mehdevi. “They are interested and at the same time want to mix a certain active joyfulness with learning, with some aspects of research.” Presently the center brings about 150 artists a year from abroad.

“The center has put itself absolutely at the heart of the Parisian process of artists meeting each other,” says Pillsbury.

How American is the center? “Very,” says Pillsbury. “It’s very pragmatic, very empirical—‘let’s try it and see.’ The founders had the money, they found good land, they made a nice building.”

As Jack Lang, the French minister of culture, told Pisar: “You know, we all have a lot to learn from you. You are the model example of what a cultural institution should be.”

* * * *

Coda: Throughout the 1980s, the American Center became so active that its directors began to have greater ambitions for the institution. Late in the decade, faced with a building in need of serious repairs, they went into contract with the city of Paris for a lot in the Bercy district and hired architect Frank Gehry to design a grand new building. The reborn American Center finally opened in 1994, but between its hefty price tag, a substantial operating budget, and accumulated debt, the building was put up for sale less than two years later. The state eventually bought the building and, after extensive renovations, at last in 2005 it became the thriving new home of the Cinémathèque Française.