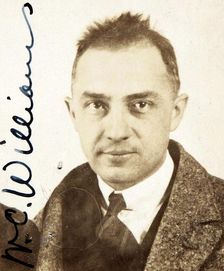

William Carlos Williams

By Word of Mouth: Poems from the Spanish, 1916-1959

Compiled and edited by Jonathan Cohen

New York: New Directions, 2011

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 85 (Nov 2012)

Some books, long obvious that they should exist, nonetheless emerge slowly into the world. Almost fifty years after his death, incredibly, the great American poet William Carlos Williams has published his first book of translations. Thanks to Jonathan Cohen, who had the skill and the care—and the awareness—to bring the book into existence, we now have a more complete picture of Williams’s poetic practice.

With his ear famously attuned to the rhythms and tones of American vernacular, Williams was rare among poets of his generation in the United States, having grown up in a bilingual household. His father was an Englishman raised mostly in the Dominican Republic, while his mother was from Puerto Rico, a descendant of French Basque and Dutch Jewish immigrants, the latter from Spanish Jews further back. So that, in Rutherford, New Jersey, in the late nineteenth century, Williams was graced with a rather unique perspective coming from a Spanish-speaking home. His multiple cultures must have rendered a more nuanced sense of hearing in the poet of American speech. Moreover, he valued Spanish for its “independence. This lack of integration with our British past,” he wrote, “gives us an opportunity”—for a new freshness in the English language, and alternate models for the poetic line.

By Word of Mouth packs a lot into its pages. The scholarly apparatus that frames the poems, and comprises a third of the volume, proves indispensable for its understanding of what needs to be said without overdoing the matter. In his helpful foreword, Julio Marzán lays out just how fundamental the role of translator was for Williams, in his self identity socially and also conceptually as a literary modernist. Cohen, in his introduction, elaborates on these themes while discussing Williams’s specific (if infrequent) activity as a literary translator and its importance for him as a poet. Thirty pages of notes follow the poems with brief biographies of the poets, pertinent details regarding Williams, and the editorial history of the texts.

Williams translated more than two dozen poets from Latin America and Spain, mostly contemporary. The work, presented bilingually, corresponds overall to three periods, generated by particular editorial projects; in some cases, he received the original text along with a literal translation from the editors. The first batch of translations, done with his father during the First World War, was for the journal Others, a special issue devoted to Latin American poets. Then, during the Spanish Civil War, he translated poets from Spain, several for the anthology And Spain Sings: Fifty Loyalist Ballads Adapted by American Poets (1937). Later, starting with his translation of Luis Palés Matos (“Prelude in Boricua”), Williams turned his attention back to Latin American poets; most of this work he did for a feature in an issue of New World Writing in 1958, including poems by Pablo Neruda, Nicanor Parra, Silvina Ocampo, Ernesto Mejía Sánchez, and Jorge Carrera Andrade.

In poets of more formal or ornate styles here, it is not always easy to recognize Williams. Occasionally, his choices are puzzling—transposing an adjective or an action away from its intended subject in the original, or simply producing an unnatural-sounding English (“lightnings” for relámpagos)—though he also allows for the playfulness of accidental suggestion (“the laurel / [dreams] of the all-seeing heart,” where el ciervo transparente really refers to an animal, the hart). Most often, his solutions seem inspired, granting a turn of phrase that echoes his own sensibilities molded by external restraints. Especially at such moments, whether or not the lines sound at their ease, the reader can discern Williams’s poetic impulse wrestling with the inevitable foreignness.

Certain poets, like Neruda with his elemental odes and Parra with his anti-poetry, would appear to be a natural fit for the tonalities of voice found in Williams. Even so, his translator’s art, with its endless subtleties and meticulous calibrations, might best be appreciated there where the lines are most akin to speech, as in the first strophe of Cuban poet (and longtime New Yorker) Eugenio Florit’s long poem “Conversation with My Father”:

Claro que ya lo sabes Clearly you already know it

que ya lo sabes todo you already know it all

todo lo sabes claro. know it all clearly.

Por eso también sabes Because of this you know too

que tengo ganas de contártelo, how I wish to tell it,

porque mientras lo cuento lo recuerdo for while I speak I am recalling

y así juntos los dos lo recordamos: as I sit here beside you:

y yo escribiendo I writing

y tú en silencio a mi lado. and you silent beside me.

The details of the words—their placement, their directionality and grammatical weight—can be treated any number of ways. But Williams knows that not all repetitions are the same, and that if you angle certain lines a little differently than given in the original (“how I wish to tell it,” “as I sit here beside you”), it might even be more effective in English. Williams is carving these lines very precisely, there is no waste, all that’s left is the music.

By Word of Mouth: Poems from the Spanish, 1916-1959

Compiled and edited by Jonathan Cohen

New York: New Directions, 2011

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 85 (Nov 2012)

Some books, long obvious that they should exist, nonetheless emerge slowly into the world. Almost fifty years after his death, incredibly, the great American poet William Carlos Williams has published his first book of translations. Thanks to Jonathan Cohen, who had the skill and the care—and the awareness—to bring the book into existence, we now have a more complete picture of Williams’s poetic practice.

With his ear famously attuned to the rhythms and tones of American vernacular, Williams was rare among poets of his generation in the United States, having grown up in a bilingual household. His father was an Englishman raised mostly in the Dominican Republic, while his mother was from Puerto Rico, a descendant of French Basque and Dutch Jewish immigrants, the latter from Spanish Jews further back. So that, in Rutherford, New Jersey, in the late nineteenth century, Williams was graced with a rather unique perspective coming from a Spanish-speaking home. His multiple cultures must have rendered a more nuanced sense of hearing in the poet of American speech. Moreover, he valued Spanish for its “independence. This lack of integration with our British past,” he wrote, “gives us an opportunity”—for a new freshness in the English language, and alternate models for the poetic line.

By Word of Mouth packs a lot into its pages. The scholarly apparatus that frames the poems, and comprises a third of the volume, proves indispensable for its understanding of what needs to be said without overdoing the matter. In his helpful foreword, Julio Marzán lays out just how fundamental the role of translator was for Williams, in his self identity socially and also conceptually as a literary modernist. Cohen, in his introduction, elaborates on these themes while discussing Williams’s specific (if infrequent) activity as a literary translator and its importance for him as a poet. Thirty pages of notes follow the poems with brief biographies of the poets, pertinent details regarding Williams, and the editorial history of the texts.

Williams translated more than two dozen poets from Latin America and Spain, mostly contemporary. The work, presented bilingually, corresponds overall to three periods, generated by particular editorial projects; in some cases, he received the original text along with a literal translation from the editors. The first batch of translations, done with his father during the First World War, was for the journal Others, a special issue devoted to Latin American poets. Then, during the Spanish Civil War, he translated poets from Spain, several for the anthology And Spain Sings: Fifty Loyalist Ballads Adapted by American Poets (1937). Later, starting with his translation of Luis Palés Matos (“Prelude in Boricua”), Williams turned his attention back to Latin American poets; most of this work he did for a feature in an issue of New World Writing in 1958, including poems by Pablo Neruda, Nicanor Parra, Silvina Ocampo, Ernesto Mejía Sánchez, and Jorge Carrera Andrade.

In poets of more formal or ornate styles here, it is not always easy to recognize Williams. Occasionally, his choices are puzzling—transposing an adjective or an action away from its intended subject in the original, or simply producing an unnatural-sounding English (“lightnings” for relámpagos)—though he also allows for the playfulness of accidental suggestion (“the laurel / [dreams] of the all-seeing heart,” where el ciervo transparente really refers to an animal, the hart). Most often, his solutions seem inspired, granting a turn of phrase that echoes his own sensibilities molded by external restraints. Especially at such moments, whether or not the lines sound at their ease, the reader can discern Williams’s poetic impulse wrestling with the inevitable foreignness.

Certain poets, like Neruda with his elemental odes and Parra with his anti-poetry, would appear to be a natural fit for the tonalities of voice found in Williams. Even so, his translator’s art, with its endless subtleties and meticulous calibrations, might best be appreciated there where the lines are most akin to speech, as in the first strophe of Cuban poet (and longtime New Yorker) Eugenio Florit’s long poem “Conversation with My Father”:

Claro que ya lo sabes Clearly you already know it

que ya lo sabes todo you already know it all

todo lo sabes claro. know it all clearly.

Por eso también sabes Because of this you know too

que tengo ganas de contártelo, how I wish to tell it,

porque mientras lo cuento lo recuerdo for while I speak I am recalling

y así juntos los dos lo recordamos: as I sit here beside you:

y yo escribiendo I writing

y tú en silencio a mi lado. and you silent beside me.

The details of the words—their placement, their directionality and grammatical weight—can be treated any number of ways. But Williams knows that not all repetitions are the same, and that if you angle certain lines a little differently than given in the original (“how I wish to tell it,” “as I sit here beside you”), it might even be more effective in English. Williams is carving these lines very precisely, there is no waste, all that’s left is the music.