Sun Ra: The Living Future

published in The Village Voice, July 4, 1989

In the foggy dawn last Wednesday at Battery Park, the very tip of Manhattan, no musician could have been better suited to welcome the summer solstice than Sun Ra. Dressed in his pharaoh’s hat and bright apricot robe, accompanied by five members of his stellar Arkestra plus Don Cherry, Ra played for nearly 200 people in the 17th annual celebration organized by Charlie Morrow and the New Wilderness Foundation. While the city slept, Ra steered the island through the harbor, standing at his keyboards, the cool captain of a mighty ship.

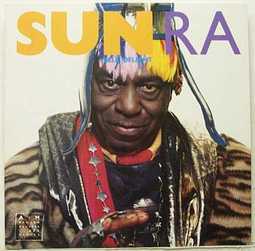

A patriarch of avant-garde jazz, Ra came up through the big band era. His Arkestra, founded in mid-1950s Chicago and now based in Philadelphia, pioneered collective improvisation in a large group setting while seeking always to have fun, with their dazzling costumes and onstage antics. Once dismissed as a space case, then revered as a prophet, Ra’s renown has steadily grown. Yet, despite more than a hundred records to his credit, his new album Blue Delight (A&M), with the Arkestra at 19 pieces strong, is his first major American label release. That’s a curious distinction for a man in his late seventies, and pop indicators like airplay suggest that A&M has a hit on its hands.

The Arkestra swings hard, with tight arrangements, rich sweeping harmonies, and solos that really do reach into space. As the title tune of the album amply shows, Sun Ra himself sends it all into motion with the walloping yet subdued way he voices the piano. The power of the band rises and softens according to his sparest inflections. What emerges time and again is 1001 ways of reading the blues. Even when playing synthesizer, where he has carved his own highly unique sound for 30 years, as in Blue Delight’s “They Dwell on Other Planes,” the angular shimmering effects serve to enhance a lyric gesture. Ra likes to sing, but the new album showcases the mastery of his musicianship.

Through the last decade, Ra has returned with a bounding joy to the music of his youth, embracing clear romantic melodies and a more cohesive group sound. The band pays full respect to the standards it plays, as on “Out of Nowhere” and “Days of Wine and Roses,” while bouncing fresh light off them. Ra expands the harmonic colors of the original, elaborating on its rhythms. When the Arkestra performs Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson material, or its set of music from Disney films, they bring down the house in romping recognition of something old being made new again. Ra appears perennially serene, his music and manner pointing the way beyond, assured of his place in the cosmos (he says he comes from Saturn). He has had the wisdom to endure, to celebrate the spirits that abide in him.

*

[NB: Check out the phenomenal 14-CD set that Michael D. Anderson put together---Sun Ra, The Eternal Myth Revealed, Vol.1 (1941-1959) (Transparency, 2011)---a comprehensive and very revealing account of Sun Ra's early career, full of terrific interviews, analysis, and rare period recordings. Out of this world!]

* * *

Sun Ra: Art on Saturn

Irwin Chusid and Chris Reisman

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2022

published in The Wire 465 (Nov. 2022)

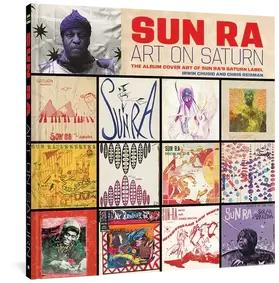

Sun Ra: Art on Saturn is a pleasure to behold. In big, 12-inch album-size pages, the book offers a sumptuous tribute to the record cover art on Sun Ra’s label, Saturn. As if one might know the band by eyes alone: the iconography and design, the imagination and resourcefulness found in the covers suggest transports not unlike those experienced by listening. Through some seventy LPs, from the 1950s to the ‘80s, Ra and his Arkestra presented their music in editions to be sold mostly at concerts. For a long while, the covers were preprinted, but in the 1970s album design turned into a more homemade affair, assembled as needed, in which everyone in the Arkestra participated. The technology of the mass-produced multiple was thus subverted, where every item became unique; and for the labels affixed to the vinyl as well. Given the well-defined scope of the materials, the book would seem preordained: as documentation of a particular creative activity, celebrating its collective spirit.

But if this volume is really about packaging, “how Sun Ra packaged his own music,” as archival wizard Irwin Chusid notes in his introduction, the challenge for the editors was to determine the nature of the package that is the book itself. The preprinted covers included some measure of variations, but the handmade covers showed a limitless reach of possibilities. What’s more, those covers often bore no title—a cataloguer’s nightmare, which musician Glenn Jones recounts from the years in the late ‘70s when he worked for Rounder Records distribution and the efforts it took him to bring the Saturn catalogue into the fold, let alone procuring two hundred copies of each new release and then getting on the phone with the Arkestra house in Philadelphia to figure out the title. For a book to contain the range of that artwork, representing the best of what’s known to exist, was no small task. Fortunately, there are many devoted collectors of Saturn records—chief among them Chris Reisman, who provides a discography of the label—which meant a surfeit of examples to choose from and organize.

Rhythmically, the book is smartly laid out, building its effects. Amid unused covers and rough drafts for illustrations, the few brief texts guide us ever further into the world of these records, culminating in John Corbett’s insightful history of Sun Ra and the label, with a detailed assessment of the cover art, its styles and methods and experiments. The ample section displaying the printed covers and labels achieves an easy balance alternating among full and quarter-size reproductions, granting a substantial sense of the Ra visual universe. But enticing as these images are, the unbridled florescence of the whole enterprise resides in the handmade covers (for all their less-polished appearance and lack of written information), seen all in full-page panels that take up the bulk of the book: collage, handpainted photos and abstract patterns, repurposed old printed covers, different color motifs for the same strange drawing, many trimmed or laminated with a patch of transparent shower curtain. Poring over them, we soon lose track of where we are, swept up in a realm of mystery and other spaces. And we haven’t even gotten to the music yet.

published in The Village Voice, July 4, 1989

In the foggy dawn last Wednesday at Battery Park, the very tip of Manhattan, no musician could have been better suited to welcome the summer solstice than Sun Ra. Dressed in his pharaoh’s hat and bright apricot robe, accompanied by five members of his stellar Arkestra plus Don Cherry, Ra played for nearly 200 people in the 17th annual celebration organized by Charlie Morrow and the New Wilderness Foundation. While the city slept, Ra steered the island through the harbor, standing at his keyboards, the cool captain of a mighty ship.

A patriarch of avant-garde jazz, Ra came up through the big band era. His Arkestra, founded in mid-1950s Chicago and now based in Philadelphia, pioneered collective improvisation in a large group setting while seeking always to have fun, with their dazzling costumes and onstage antics. Once dismissed as a space case, then revered as a prophet, Ra’s renown has steadily grown. Yet, despite more than a hundred records to his credit, his new album Blue Delight (A&M), with the Arkestra at 19 pieces strong, is his first major American label release. That’s a curious distinction for a man in his late seventies, and pop indicators like airplay suggest that A&M has a hit on its hands.

The Arkestra swings hard, with tight arrangements, rich sweeping harmonies, and solos that really do reach into space. As the title tune of the album amply shows, Sun Ra himself sends it all into motion with the walloping yet subdued way he voices the piano. The power of the band rises and softens according to his sparest inflections. What emerges time and again is 1001 ways of reading the blues. Even when playing synthesizer, where he has carved his own highly unique sound for 30 years, as in Blue Delight’s “They Dwell on Other Planes,” the angular shimmering effects serve to enhance a lyric gesture. Ra likes to sing, but the new album showcases the mastery of his musicianship.

Through the last decade, Ra has returned with a bounding joy to the music of his youth, embracing clear romantic melodies and a more cohesive group sound. The band pays full respect to the standards it plays, as on “Out of Nowhere” and “Days of Wine and Roses,” while bouncing fresh light off them. Ra expands the harmonic colors of the original, elaborating on its rhythms. When the Arkestra performs Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson material, or its set of music from Disney films, they bring down the house in romping recognition of something old being made new again. Ra appears perennially serene, his music and manner pointing the way beyond, assured of his place in the cosmos (he says he comes from Saturn). He has had the wisdom to endure, to celebrate the spirits that abide in him.

*

[NB: Check out the phenomenal 14-CD set that Michael D. Anderson put together---Sun Ra, The Eternal Myth Revealed, Vol.1 (1941-1959) (Transparency, 2011)---a comprehensive and very revealing account of Sun Ra's early career, full of terrific interviews, analysis, and rare period recordings. Out of this world!]

* * *

Sun Ra: Art on Saturn

Irwin Chusid and Chris Reisman

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2022

published in The Wire 465 (Nov. 2022)

Sun Ra: Art on Saturn is a pleasure to behold. In big, 12-inch album-size pages, the book offers a sumptuous tribute to the record cover art on Sun Ra’s label, Saturn. As if one might know the band by eyes alone: the iconography and design, the imagination and resourcefulness found in the covers suggest transports not unlike those experienced by listening. Through some seventy LPs, from the 1950s to the ‘80s, Ra and his Arkestra presented their music in editions to be sold mostly at concerts. For a long while, the covers were preprinted, but in the 1970s album design turned into a more homemade affair, assembled as needed, in which everyone in the Arkestra participated. The technology of the mass-produced multiple was thus subverted, where every item became unique; and for the labels affixed to the vinyl as well. Given the well-defined scope of the materials, the book would seem preordained: as documentation of a particular creative activity, celebrating its collective spirit.

But if this volume is really about packaging, “how Sun Ra packaged his own music,” as archival wizard Irwin Chusid notes in his introduction, the challenge for the editors was to determine the nature of the package that is the book itself. The preprinted covers included some measure of variations, but the handmade covers showed a limitless reach of possibilities. What’s more, those covers often bore no title—a cataloguer’s nightmare, which musician Glenn Jones recounts from the years in the late ‘70s when he worked for Rounder Records distribution and the efforts it took him to bring the Saturn catalogue into the fold, let alone procuring two hundred copies of each new release and then getting on the phone with the Arkestra house in Philadelphia to figure out the title. For a book to contain the range of that artwork, representing the best of what’s known to exist, was no small task. Fortunately, there are many devoted collectors of Saturn records—chief among them Chris Reisman, who provides a discography of the label—which meant a surfeit of examples to choose from and organize.

Rhythmically, the book is smartly laid out, building its effects. Amid unused covers and rough drafts for illustrations, the few brief texts guide us ever further into the world of these records, culminating in John Corbett’s insightful history of Sun Ra and the label, with a detailed assessment of the cover art, its styles and methods and experiments. The ample section displaying the printed covers and labels achieves an easy balance alternating among full and quarter-size reproductions, granting a substantial sense of the Ra visual universe. But enticing as these images are, the unbridled florescence of the whole enterprise resides in the handmade covers (for all their less-polished appearance and lack of written information), seen all in full-page panels that take up the bulk of the book: collage, handpainted photos and abstract patterns, repurposed old printed covers, different color motifs for the same strange drawing, many trimmed or laminated with a patch of transparent shower curtain. Poring over them, we soon lose track of where we are, swept up in a realm of mystery and other spaces. And we haven’t even gotten to the music yet.