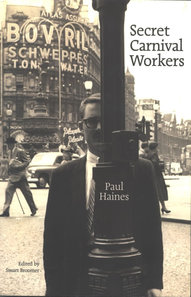

_Paul Haines, Secret Carnival Workers

Edited by Stuart Broomer

Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 77 (Nov. 2008)

For a writer who never made a career of his art, Paul Haines (1932-2003) sure mixed with impressive company. Less inclined toward a literary crowd, he was rather a musician’s writer. Certainly his ears led him and fed him in the construction of sense, and in the playful pivoting rhythms of his phrases multiple readings opened forth. A poet foremost, he savored language not so much for its usefulness as for the tickle of discovery, of unexpected insights it offered. Secret Carnival Workers, which gathers much of his writings, thus presents the evidence: it is a box of jewels for a rainy day, a field of chiming mirrors.

Haines published just one small book of poems in his lifetime, Third World Two (1981). Nearly half of the new collection, a hundred pages, is taken up with his poems; the rest comprises early experimental fiction, numerous pieces on jazz, brief appreciations by longtime musical associates (Carla Bley, Roswell Rudd, Michael Snow), and an incisive analysis of his literary relation to music by editor (and musician) Stuart Broomer. What Haines was best known for, after all, was the remarkable settings of his poems heard on a half-dozen records, starting with Bley’s monumental jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill (1971).

An avid listener since his youth in Michigan, Haines had lived in Europe and the Middle East before moving to New York, where he became a friend and proponent of the new jazz during the early 1960s. Occasionally serving as the recording engineer on what would come to be seen as historic sessions, he also wrote singularly distinctive liner notes for landmark albums by Paul Bley, Albert Ayler, and the Jazz Composers Orchestra. In these, as in notes much later for records by Evan Parker, Kip Hanrahan, and the CCMC (Canadian Creative Music Collective), he managed to blend uncompromising musical commentary, quirky philosophical inquiry, narrative sleights of hand, and oblique linguistic leaps, to fashion texts as rich and beguiling and by turns impenetrable as the music. If the reader might not quite guess at the sounds that occasioned such writing, a mind was at work there---at work and also at play---which prepared the prospective listener at least to enter the theater of possibilities. This resourcefulness of style, upending expectations, permeated all his writings on music---especially his quasi-phenomenological essay, through a Cortazarian-type lens, on the life of sounds (“Jubilee”).

In his poems, Haines proved equally difficult to categorize. Schooled in the modernists, especially the French, he tended toward a colloquial voice but where an uncommon word, a subtle twist of syntax, a roving ear, could well subvert appearances. He dealt in short lines, provocatively chiseled line breaks, unsettling word clusters, and he showed a fine instinct for the sensual confluences of sound and meaning. Even his titles offered something to chew on: “What Is Free to a Good Home?,” “Route Doubt,” “For All Intense Purposes.” Often, the poem’s full measure relied on suggestion, echo, the underside of what’s said, as in “Today,” delicately recorded by saxophonist George Cartwright and the band Curlew in 1993 (all capitals was Haines’s style):

WHILE YOU

WERE OUT

I WAS

IN

NOT THAT I

COULD BE

HIM

BUT THAT HE

COULD BE

ME

If it was from shared affinities that improvising musicians took to his poems, what was most remarkable was how different the results. In Escalator and again in Tropic Appetites (1974), based on poems Haines wrote at the time while teaching in India, Carla Bley assembled a stellar band with Gato Barbieri among the soloists plus, in the earlier work, Jack Bruce and Linda Ronstadt as vocalists; Bley’s treatments drew most directly from the theatrical tradition typified by the Brecht-Weill collaborations. In 1983, by contrast, Kip Hanrahan’s Desire Develops an Edge included settings of three Haines poems, with Bruce singing over layers of Afro-Caribbean rhythms and a lush weave of horns and guitars.

By the mid-1970s, Haines had moved with his family to Fenelon Falls, Ontario, where he taught high-school French for most of the next three decades while his writing drew the attention of younger musicians and he also began to make a series of short, music-related films. His own Darn It! (1994), the most ambitious of all his record projects, produced by Hanrahan, proved how fertile his poems could be for the imaginative ear. With some thirty years of musical friends, over two discs, each performance was more surprising than the next.

So, how do his poems fare on their own quietly in a book? As Roswell Rudd put it, “Eternal grist to grind on.”

Edited by Stuart Broomer

Toronto: Coach House Books, 2007

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 77 (Nov. 2008)

For a writer who never made a career of his art, Paul Haines (1932-2003) sure mixed with impressive company. Less inclined toward a literary crowd, he was rather a musician’s writer. Certainly his ears led him and fed him in the construction of sense, and in the playful pivoting rhythms of his phrases multiple readings opened forth. A poet foremost, he savored language not so much for its usefulness as for the tickle of discovery, of unexpected insights it offered. Secret Carnival Workers, which gathers much of his writings, thus presents the evidence: it is a box of jewels for a rainy day, a field of chiming mirrors.

Haines published just one small book of poems in his lifetime, Third World Two (1981). Nearly half of the new collection, a hundred pages, is taken up with his poems; the rest comprises early experimental fiction, numerous pieces on jazz, brief appreciations by longtime musical associates (Carla Bley, Roswell Rudd, Michael Snow), and an incisive analysis of his literary relation to music by editor (and musician) Stuart Broomer. What Haines was best known for, after all, was the remarkable settings of his poems heard on a half-dozen records, starting with Bley’s monumental jazz opera, Escalator Over The Hill (1971).

An avid listener since his youth in Michigan, Haines had lived in Europe and the Middle East before moving to New York, where he became a friend and proponent of the new jazz during the early 1960s. Occasionally serving as the recording engineer on what would come to be seen as historic sessions, he also wrote singularly distinctive liner notes for landmark albums by Paul Bley, Albert Ayler, and the Jazz Composers Orchestra. In these, as in notes much later for records by Evan Parker, Kip Hanrahan, and the CCMC (Canadian Creative Music Collective), he managed to blend uncompromising musical commentary, quirky philosophical inquiry, narrative sleights of hand, and oblique linguistic leaps, to fashion texts as rich and beguiling and by turns impenetrable as the music. If the reader might not quite guess at the sounds that occasioned such writing, a mind was at work there---at work and also at play---which prepared the prospective listener at least to enter the theater of possibilities. This resourcefulness of style, upending expectations, permeated all his writings on music---especially his quasi-phenomenological essay, through a Cortazarian-type lens, on the life of sounds (“Jubilee”).

In his poems, Haines proved equally difficult to categorize. Schooled in the modernists, especially the French, he tended toward a colloquial voice but where an uncommon word, a subtle twist of syntax, a roving ear, could well subvert appearances. He dealt in short lines, provocatively chiseled line breaks, unsettling word clusters, and he showed a fine instinct for the sensual confluences of sound and meaning. Even his titles offered something to chew on: “What Is Free to a Good Home?,” “Route Doubt,” “For All Intense Purposes.” Often, the poem’s full measure relied on suggestion, echo, the underside of what’s said, as in “Today,” delicately recorded by saxophonist George Cartwright and the band Curlew in 1993 (all capitals was Haines’s style):

WHILE YOU

WERE OUT

I WAS

IN

NOT THAT I

COULD BE

HIM

BUT THAT HE

COULD BE

ME

If it was from shared affinities that improvising musicians took to his poems, what was most remarkable was how different the results. In Escalator and again in Tropic Appetites (1974), based on poems Haines wrote at the time while teaching in India, Carla Bley assembled a stellar band with Gato Barbieri among the soloists plus, in the earlier work, Jack Bruce and Linda Ronstadt as vocalists; Bley’s treatments drew most directly from the theatrical tradition typified by the Brecht-Weill collaborations. In 1983, by contrast, Kip Hanrahan’s Desire Develops an Edge included settings of three Haines poems, with Bruce singing over layers of Afro-Caribbean rhythms and a lush weave of horns and guitars.

By the mid-1970s, Haines had moved with his family to Fenelon Falls, Ontario, where he taught high-school French for most of the next three decades while his writing drew the attention of younger musicians and he also began to make a series of short, music-related films. His own Darn It! (1994), the most ambitious of all his record projects, produced by Hanrahan, proved how fertile his poems could be for the imaginative ear. With some thirty years of musical friends, over two discs, each performance was more surprising than the next.

So, how do his poems fare on their own quietly in a book? As Roswell Rudd put it, “Eternal grist to grind on.”