Milan Kundera

Portions of this interview were first published in the Los Angeles Times (December 26, 1984); the entire text appeared in the New England Review VIII:3 (Spring 1986), and later in my book Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (1991), now out of print.

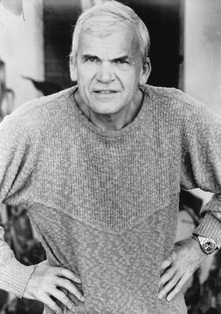

At fifty-five, Milan Kundera has matured handsomely. Yet the boyish quickness still lingers, in the penetrating light of his smile and in the way he bounds across the bright living room of his Montparnasse flat in Paris to answer the phone. Tall, slim, gracious, he seems hardly fazed by his growing celebrity.

Since the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague, Kundera’s books were banned in his native Czechoslovakia. In 1975 he and his wife came to France and since then, his books have had their first publication in French translation, with a small Czech edition published in Canada. His novels have won major awards in France, Italy and the United States, and his latest work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, was made into a major American film in 1988.

Kundera thinks of the novel as a form of meditation. In his work, the story is like an object turning in the writer’s hands, gathering reflections as it goes. His lucidity stokes the narratives along, at each bend revealing the human paradox. At the same time, Kundera tells a good story, and his formal innovations have enabled him to employ a wide range of modes in his novels.

The following interview took place in late November 1984.

How did you begin writing your latest novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being? What was the germ? How did you develop it?

That’s rather a long story. For example, the meeting of Tomas and Tereza I’d wanted to write around twenty-five years ago. It was even a first novel that I wrote, but completely unsuccessfully, which I set aside. But I held onto it anyway, this story that I didn’t know how to write. It was a very, very long gestation. I wrote other novels, but always with an idea that one day I’m going to return to this story. When I came to France, I told myself, “Now I’m going to write this novel about Tomas and Tereza,” though at the time they had other names. All of a sudden I had the feeling that I wasn’t strong enough, or ready enough, to do it. So, I put it off once more, and I began The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. After finishing that book I set about once again to write this novel. From the point of view of the motifs, it was already prepared.

For me, it’s always a question of counterpoint. You have a story, for example that story of Tamina in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, it fascinated me a lot but it was never right. Suddenly, I was searching for another motif that could create a harmony with this story. I found this harmony in thinking of joining it with a memory that was completely real, the death of my father. And at that moment, I knew that was it. Here perhaps it’s the same thing, the counterpoint of this story was that of Sabina and Franz. That was the long search, it was a wandering, really. The moment I understood that it really does make a whole novelistically, then I saw that it worked.

With this notion of counterpoint, how do you manage to find a balance among the elements? How do you search for it?

It’s a question of sensibilities. You know, all the theories that I’m telling you, they are a posteriori. I never realized that that’s what polyphony is, it was only after the fact when I began to reflect on what I’d done. So I said that it’s a certain method, but a spontaneous one. It’s not cerebral.

Discussions, the play of ideas, are always present amid your stories. Even the title of your last novel could be that of a philosophy book. Does it ever worry you that you might be getting too close to the realm of ideas and lose the story?

Not at all. Of course, from the point of view, I don’t know, of Flaubert, to intervene in the story in this way would be impossible, in bad taste. Because it’s another esthetic, one that wanted the author to disappear completely from the objectivity of his observations. But my esthetic is different; it’s the contrary. I would like for everything to be reflected upon. Even if I relate how you’re drinking whiskey right now, that must be part of a reflection. But not one which is philosophical; rather, a novelistic reflection. That’s different. You know, it’s a mistake for us to consider thought as boring. That’s not true. Novelistic thought must be the contrary, it engages the attention. We have to make thought captivating, we have to give it suspense. We’re distrustful in regards to thought, which is perhaps the question of the revolution of modern society, because we cease to think. That is, when someone starts to think, to reflect, then we’re a bit shocked; is it possible? how? I think of the novel as a form of meditation. But I know that I’m going counter-current to the times.

Reading the passages where there are discussions of ideas, one might expect that it’ll soon get boring, but it doesn’t.

No, because it’s always connected to the story, to the situation; it’s always connected to the characters. I start with Nietzsche in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, but one doesn’t realize that this beginning with Nietzsche is an introduction to Tomas, to the problematic existence of Tomas. So, it’s a novelistic meditation, connected to a character. Secondly, it’s a provocation. What I say about the eternal return, it’s an intellectual provocation.

If you see yourself as going counter-current, what is the current then?

Journalistic thought. I’m not thinking only of being counter-current to the evolution of the novel. On the contrary, it’s to the spirit of the times. We leave less and less room for thought, for really thinking. And we replace thought with the non-thinking of the mass media. We’re encumbered by information, but we no longer try to pose questions. To stop, to reflect, is something which modern society gives no place to anymore.

Considering your concern with the rational, were you ever interested in surrealism, say, where the irrational is so important?

I’m not going to oppose the irrational with the rational. That opposition doesn’t even mean much to me. Because we are rational in order to get hold of the irrational, right? We are irrational in order to awaken the imagination, and it’s the imagination which is there to understand the world better. I want to cultivate both my irrational and my rational sides. So, both the lucidity of reflection and the imagination completely unbound. I would even say that it’s my greatest esthetic challenge, to create in the novel a space where the coldest rationality could cohabit with the freest imagination. Which isn’t easy. But I believe the novel gives you this occasion to connect such things.

One of the themes that runs through all your books is the separation of the body and the soul. Which is a rather fundamental concern for religion too. Has the religious or even mystic aspect of that question been of much interest to you?

No. For me the question of the body and the soul is the fundamental question in the metaphysics of love.

I’m fascinated by the sinuous play of the plots in your novels. You seem to delight in their possible twists, pushing them to the limit.

The modern novel has had a sort of complex, as if the novel were ashamed of being a novel. A novelist often says, “But what I’ve written, it’s not really a novel.” The nouveau roman novelists in France said, “We’re writing an anti-novel.” That is, this shame with regard to the novel is something I do not share. On the contrary, I think that the importance of the novel in European culture has been enormous; European man is unthinkable without the novel, he was created by it. For centuries it was the first thing one read. The love of adventure, which is so European, adventure understood as a value. If you say, “I lived my life without adventure,” then it’s a failure, right? Well, it’s the novel that impressed upon us this love of adventure.

And the understanding of others, the element of characters. Which is another shame of the novel. The French no longer say “the novel,” they say l'écriture (writing): “In my writing, the character is already a thing of the past.” Trying to construct someone who isn’t you, it’s an extraordinary way out of your egocentricity, to understand someone who thinks differently than you. And not only to understand him, but in a certain sense to defend him against yourself even. And that’s very European.

The novel has not exploited all its possibilities. There are a lot of things the novel could have done and didn’t, because after all every story is in a certain sense a failure. Every life is a failure: at the end of your life you might say, “I should have fucked more women, I should have written better things,” etcetera. And at the end of the life in the novel you can have the same reproaches. That is, I do not have that shame either as regards characters or adventure. Why be afraid to relate an adventure? That all depends on how you tell it. You can tell it in a way that’s so conventional that it doesn’t mean anything. But being against the conventional novel, I would never speak against the traditional novel. For example, here in France this break in the discourse among people who speak on one side for the modern novel and on the other side for the traditional novel: I find that to be of an infinite stupidity. Because, first, what is the traditional novel, where does it end? It’s an amalgam; there are various phases of the novel. And then, each phase of the so-called traditional novel was always the anti-conventional novel of its time. Flaubert is a traditional writer? How can that be? His work was the biggest revolution in the history of the novel. But one is against the conventional novel, the novel that discovers nothing new.

You first read Kafka when you were fourteen. What did his work mean for you in your development as a writer?

The great experience of reading Kafka changed my way of seeing literature. Above all, it was a lesson in liberty, suddenly you’ve understood that the novel isn’t obligated to imitate reality. It’s something else, a world that’s autonomous. How you construct this autonomous world, that’s already your business. But Kafka tells us, You mustn’t naively imitate reality, you are completely free, you can invent whatever you want, now it depends on you. That is, there are thousands of possibilities; Kafka’s lesson is an esthetic one rather than philosophic. And then, he also tells us that the novel is a question of the imagination. Because in the nineteenth century the aspect of observation in the novel had evolved greatly, with Flaubert. It was brilliant, the novel knew how to see, to observe. And Kafka held on to that faculty of observation, but he says at the same time, You have to also engage an imagination, you have to know how to free it. I’d say that the density of imagination—if we could measure the quantity of imagination within a certain space—well, the density of imagination for Kafka is a hundred times greater than for any other writer. And that is Kafka’s invitation: free yourself.

In The Joke, Ludvik says at one point, “Youth is a terrible thing.” Was your youth so terrible?

Certain experiences are personal ones. When I was twenty, it was the arrival of Stalinism, of the terror of Stalinism. And that terror was supported above all by the young people. Because the young saw in it a revolt, against the old world and so on. Little by little, that led me to pose to myself not only the question of terror, but also the question of youth. So, I never had that adoring attitude that people have in regard to the young. Even when I was young myself.

The character, Ludvik, goes on to reflect on “the terrible restlessness of waiting to grow up.” You started your first novel when you were in your early 30s. Why did you not start writing earlier?

I can’t even imagine writing a novel before the age of thirty. I don’t think it works. Because not only is there not enough experience, but especially there isn’t the experience of time. I felt myself to be very young then, and I was, thirty-three, that’s young. So, the critique of youth has always interested me a lot. And it’s not bitterness either, rather it’s a self-critique. Because if I recall myself as a young man, I am not at all of an enthusiasm or a lyric nostalgia. I sooner tell myself, “This jerk that I was, I wouldn’t like to see him.” I do not live at peace with myself at twenty. I feel myself to have been an absolute jerk from every point of view, and it likely comes from there, this suspicious attitude toward that age, especially with regard to a certain lyricizing.

You came from a musical family. Did you never think of a career in music?

Yes, I even had a certain musical education, which I abandoned completely at the age of eighteen. But it left me with a rather large knowledge of music, and the love of music too.

You’ve often spoken of the importance of counterpoint in your writing. Has music brought other contributions to your work?

Certainly. Especially the sense of form, the sense of rhythm, tempo. Repetition, variation.

You also played jazz when you were young.

Jazz perhaps isn’t the right word. At a certain point without work, when I was very young, twenty-two or twenty-three, I earned my living playing piano with a few friends in the bistros.

Did you like listening to jazz much?

Yes, quite a bit. You know, it was at the time when the Iron Curtain had really fallen, after ’48. That is, we didn’t know contemporary jazz; what we did was our own memory of jazz, our own imitation of what we considered to be jazz. I played something like jazz, but with terrific musicians, because they were chased out of the conservatories for political reasons and so on. Perhaps we even played well. It was unclassifiable, because we played before a public that was absolutely naive, in popular bars for people to dance. So, it wasn’t a demanding public. But there was behind all that the love of jazz. Whereas popular music interested me more from the point of view of theory rather than practice, in the harmonies, the rhythm.

You’ve written certain essays, such as your piece on Kafka, in French rather than Czech. Has that changed the way you write, working in another language?

What changes is your contact with translators. Because you look at your text in the mirror of the translation. That changes something, because it is the perpetual control of their attitude toward what you’re saying. So, the fact of being translated forces you toward the greatest clarity possible.

Yet one of the more difficult things to translate is the rhythm itself of the prose.

You know, in translation the first thing is the willingness to be faithful, and that’s what is missing with the majority of translators. Because the rhythm, what is that? The rhythm is, for example, your punctuation, or the repetition of a word. You start three sentences one after the next using the same word, like that you create a certain litanic melody. It suffices to be faithful and the melody is completely retained.

Portions of this interview were first published in the Los Angeles Times (December 26, 1984); the entire text appeared in the New England Review VIII:3 (Spring 1986), and later in my book Writing at Risk: interviews in Paris with uncommon writers (1991), now out of print.

At fifty-five, Milan Kundera has matured handsomely. Yet the boyish quickness still lingers, in the penetrating light of his smile and in the way he bounds across the bright living room of his Montparnasse flat in Paris to answer the phone. Tall, slim, gracious, he seems hardly fazed by his growing celebrity.

Since the 1968 Soviet invasion of Prague, Kundera’s books were banned in his native Czechoslovakia. In 1975 he and his wife came to France and since then, his books have had their first publication in French translation, with a small Czech edition published in Canada. His novels have won major awards in France, Italy and the United States, and his latest work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, was made into a major American film in 1988.

Kundera thinks of the novel as a form of meditation. In his work, the story is like an object turning in the writer’s hands, gathering reflections as it goes. His lucidity stokes the narratives along, at each bend revealing the human paradox. At the same time, Kundera tells a good story, and his formal innovations have enabled him to employ a wide range of modes in his novels.

The following interview took place in late November 1984.

How did you begin writing your latest novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being? What was the germ? How did you develop it?

That’s rather a long story. For example, the meeting of Tomas and Tereza I’d wanted to write around twenty-five years ago. It was even a first novel that I wrote, but completely unsuccessfully, which I set aside. But I held onto it anyway, this story that I didn’t know how to write. It was a very, very long gestation. I wrote other novels, but always with an idea that one day I’m going to return to this story. When I came to France, I told myself, “Now I’m going to write this novel about Tomas and Tereza,” though at the time they had other names. All of a sudden I had the feeling that I wasn’t strong enough, or ready enough, to do it. So, I put it off once more, and I began The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. After finishing that book I set about once again to write this novel. From the point of view of the motifs, it was already prepared.

For me, it’s always a question of counterpoint. You have a story, for example that story of Tamina in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, it fascinated me a lot but it was never right. Suddenly, I was searching for another motif that could create a harmony with this story. I found this harmony in thinking of joining it with a memory that was completely real, the death of my father. And at that moment, I knew that was it. Here perhaps it’s the same thing, the counterpoint of this story was that of Sabina and Franz. That was the long search, it was a wandering, really. The moment I understood that it really does make a whole novelistically, then I saw that it worked.

With this notion of counterpoint, how do you manage to find a balance among the elements? How do you search for it?

It’s a question of sensibilities. You know, all the theories that I’m telling you, they are a posteriori. I never realized that that’s what polyphony is, it was only after the fact when I began to reflect on what I’d done. So I said that it’s a certain method, but a spontaneous one. It’s not cerebral.

Discussions, the play of ideas, are always present amid your stories. Even the title of your last novel could be that of a philosophy book. Does it ever worry you that you might be getting too close to the realm of ideas and lose the story?

Not at all. Of course, from the point of view, I don’t know, of Flaubert, to intervene in the story in this way would be impossible, in bad taste. Because it’s another esthetic, one that wanted the author to disappear completely from the objectivity of his observations. But my esthetic is different; it’s the contrary. I would like for everything to be reflected upon. Even if I relate how you’re drinking whiskey right now, that must be part of a reflection. But not one which is philosophical; rather, a novelistic reflection. That’s different. You know, it’s a mistake for us to consider thought as boring. That’s not true. Novelistic thought must be the contrary, it engages the attention. We have to make thought captivating, we have to give it suspense. We’re distrustful in regards to thought, which is perhaps the question of the revolution of modern society, because we cease to think. That is, when someone starts to think, to reflect, then we’re a bit shocked; is it possible? how? I think of the novel as a form of meditation. But I know that I’m going counter-current to the times.

Reading the passages where there are discussions of ideas, one might expect that it’ll soon get boring, but it doesn’t.

No, because it’s always connected to the story, to the situation; it’s always connected to the characters. I start with Nietzsche in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, but one doesn’t realize that this beginning with Nietzsche is an introduction to Tomas, to the problematic existence of Tomas. So, it’s a novelistic meditation, connected to a character. Secondly, it’s a provocation. What I say about the eternal return, it’s an intellectual provocation.

If you see yourself as going counter-current, what is the current then?

Journalistic thought. I’m not thinking only of being counter-current to the evolution of the novel. On the contrary, it’s to the spirit of the times. We leave less and less room for thought, for really thinking. And we replace thought with the non-thinking of the mass media. We’re encumbered by information, but we no longer try to pose questions. To stop, to reflect, is something which modern society gives no place to anymore.

Considering your concern with the rational, were you ever interested in surrealism, say, where the irrational is so important?

I’m not going to oppose the irrational with the rational. That opposition doesn’t even mean much to me. Because we are rational in order to get hold of the irrational, right? We are irrational in order to awaken the imagination, and it’s the imagination which is there to understand the world better. I want to cultivate both my irrational and my rational sides. So, both the lucidity of reflection and the imagination completely unbound. I would even say that it’s my greatest esthetic challenge, to create in the novel a space where the coldest rationality could cohabit with the freest imagination. Which isn’t easy. But I believe the novel gives you this occasion to connect such things.

One of the themes that runs through all your books is the separation of the body and the soul. Which is a rather fundamental concern for religion too. Has the religious or even mystic aspect of that question been of much interest to you?

No. For me the question of the body and the soul is the fundamental question in the metaphysics of love.

I’m fascinated by the sinuous play of the plots in your novels. You seem to delight in their possible twists, pushing them to the limit.

The modern novel has had a sort of complex, as if the novel were ashamed of being a novel. A novelist often says, “But what I’ve written, it’s not really a novel.” The nouveau roman novelists in France said, “We’re writing an anti-novel.” That is, this shame with regard to the novel is something I do not share. On the contrary, I think that the importance of the novel in European culture has been enormous; European man is unthinkable without the novel, he was created by it. For centuries it was the first thing one read. The love of adventure, which is so European, adventure understood as a value. If you say, “I lived my life without adventure,” then it’s a failure, right? Well, it’s the novel that impressed upon us this love of adventure.

And the understanding of others, the element of characters. Which is another shame of the novel. The French no longer say “the novel,” they say l'écriture (writing): “In my writing, the character is already a thing of the past.” Trying to construct someone who isn’t you, it’s an extraordinary way out of your egocentricity, to understand someone who thinks differently than you. And not only to understand him, but in a certain sense to defend him against yourself even. And that’s very European.

The novel has not exploited all its possibilities. There are a lot of things the novel could have done and didn’t, because after all every story is in a certain sense a failure. Every life is a failure: at the end of your life you might say, “I should have fucked more women, I should have written better things,” etcetera. And at the end of the life in the novel you can have the same reproaches. That is, I do not have that shame either as regards characters or adventure. Why be afraid to relate an adventure? That all depends on how you tell it. You can tell it in a way that’s so conventional that it doesn’t mean anything. But being against the conventional novel, I would never speak against the traditional novel. For example, here in France this break in the discourse among people who speak on one side for the modern novel and on the other side for the traditional novel: I find that to be of an infinite stupidity. Because, first, what is the traditional novel, where does it end? It’s an amalgam; there are various phases of the novel. And then, each phase of the so-called traditional novel was always the anti-conventional novel of its time. Flaubert is a traditional writer? How can that be? His work was the biggest revolution in the history of the novel. But one is against the conventional novel, the novel that discovers nothing new.

You first read Kafka when you were fourteen. What did his work mean for you in your development as a writer?

The great experience of reading Kafka changed my way of seeing literature. Above all, it was a lesson in liberty, suddenly you’ve understood that the novel isn’t obligated to imitate reality. It’s something else, a world that’s autonomous. How you construct this autonomous world, that’s already your business. But Kafka tells us, You mustn’t naively imitate reality, you are completely free, you can invent whatever you want, now it depends on you. That is, there are thousands of possibilities; Kafka’s lesson is an esthetic one rather than philosophic. And then, he also tells us that the novel is a question of the imagination. Because in the nineteenth century the aspect of observation in the novel had evolved greatly, with Flaubert. It was brilliant, the novel knew how to see, to observe. And Kafka held on to that faculty of observation, but he says at the same time, You have to also engage an imagination, you have to know how to free it. I’d say that the density of imagination—if we could measure the quantity of imagination within a certain space—well, the density of imagination for Kafka is a hundred times greater than for any other writer. And that is Kafka’s invitation: free yourself.

In The Joke, Ludvik says at one point, “Youth is a terrible thing.” Was your youth so terrible?

Certain experiences are personal ones. When I was twenty, it was the arrival of Stalinism, of the terror of Stalinism. And that terror was supported above all by the young people. Because the young saw in it a revolt, against the old world and so on. Little by little, that led me to pose to myself not only the question of terror, but also the question of youth. So, I never had that adoring attitude that people have in regard to the young. Even when I was young myself.

The character, Ludvik, goes on to reflect on “the terrible restlessness of waiting to grow up.” You started your first novel when you were in your early 30s. Why did you not start writing earlier?

I can’t even imagine writing a novel before the age of thirty. I don’t think it works. Because not only is there not enough experience, but especially there isn’t the experience of time. I felt myself to be very young then, and I was, thirty-three, that’s young. So, the critique of youth has always interested me a lot. And it’s not bitterness either, rather it’s a self-critique. Because if I recall myself as a young man, I am not at all of an enthusiasm or a lyric nostalgia. I sooner tell myself, “This jerk that I was, I wouldn’t like to see him.” I do not live at peace with myself at twenty. I feel myself to have been an absolute jerk from every point of view, and it likely comes from there, this suspicious attitude toward that age, especially with regard to a certain lyricizing.

You came from a musical family. Did you never think of a career in music?

Yes, I even had a certain musical education, which I abandoned completely at the age of eighteen. But it left me with a rather large knowledge of music, and the love of music too.

You’ve often spoken of the importance of counterpoint in your writing. Has music brought other contributions to your work?

Certainly. Especially the sense of form, the sense of rhythm, tempo. Repetition, variation.

You also played jazz when you were young.

Jazz perhaps isn’t the right word. At a certain point without work, when I was very young, twenty-two or twenty-three, I earned my living playing piano with a few friends in the bistros.

Did you like listening to jazz much?

Yes, quite a bit. You know, it was at the time when the Iron Curtain had really fallen, after ’48. That is, we didn’t know contemporary jazz; what we did was our own memory of jazz, our own imitation of what we considered to be jazz. I played something like jazz, but with terrific musicians, because they were chased out of the conservatories for political reasons and so on. Perhaps we even played well. It was unclassifiable, because we played before a public that was absolutely naive, in popular bars for people to dance. So, it wasn’t a demanding public. But there was behind all that the love of jazz. Whereas popular music interested me more from the point of view of theory rather than practice, in the harmonies, the rhythm.

You’ve written certain essays, such as your piece on Kafka, in French rather than Czech. Has that changed the way you write, working in another language?

What changes is your contact with translators. Because you look at your text in the mirror of the translation. That changes something, because it is the perpetual control of their attitude toward what you’re saying. So, the fact of being translated forces you toward the greatest clarity possible.

Yet one of the more difficult things to translate is the rhythm itself of the prose.

You know, in translation the first thing is the willingness to be faithful, and that’s what is missing with the majority of translators. Because the rhythm, what is that? The rhythm is, for example, your punctuation, or the repetition of a word. You start three sentences one after the next using the same word, like that you create a certain litanic melody. It suffices to be faithful and the melody is completely retained.