Ligorano/Reese

The Book Talks Back: the video books of Ligorano/Reese

published in Felix (New York) 2:1 (1995)

Despite their apparent similarity in form, the artist's book turns out to be quite a different animal than the literary artifact. The book that is mass produced serves a functional role---to make money ultimately or to win converts--- but it may be said as well of the loftier products of literature that they all play down the cover for what is inside. Whatever aesthetic considerations go into the design, it remains subordinate to the book's content. The artist's book, by contrast, radically alters this relationship.

Often presented as a unique object, and so distinguished from the infinitely reproducible text where only copies exist which can be owned by everyone, the artist's book draws attention to the mixed media of its construction. Even when it may be touched, its pages turned, it poses its own conditions in terms of reading. These conditions, however, only apply to that singular object, according to its blend of visual and sculptural elements, and its use of forms of writing, as well as the position it occupies with regard to the viewer. Text here may be largely de-emphasized or even absent, yet to read this book sets up a fruitful tension with our more usual habits of reading.

The video books of Nora Ligorano and Marshall Reese complicate this process by incorporating the most popular medium of our time, the moving image. Cut into the space of the page, a screen is placed which in effect screens out the text around it. The book becomes more like a theatrical object, the frame for the artists' strategy, or the proscenium arch itself, and the whole apparatus plays upon that central enchantment which looks strangely like television. But here the language of television is turned inside out to reveal the artifice of its illusion.

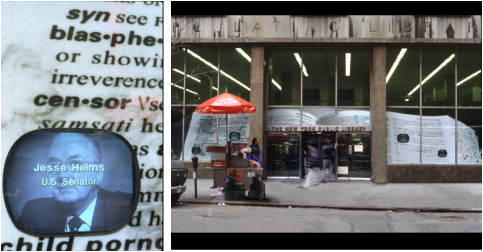

Amid their other activities as artists, Ligorano/Reese have produced three video books to date and each tackles issues in the ongoing cultural debate in the United States. Their latest work, Acid Migration of Culture (1994), stands as their most ambitious yet and also their most public. A large and elaborate installation, throughout the month of January it occupied the main windows of the Donnell Library, the branch of the New York Public Library directly across from the Museum of Modern Art. The piece concerns the hot topic of censorship and the arts and includes statements from about fifty artists, critics, politicians, and religious leaders. The frame in this case is a 45-foot long photo mural that shows the open pages of a dictionary which, in fact, was composed on a computer, since the words defined on these two pages cover the entire alphabet: terms such as 'art,' 'blasphemy,' 'civilization,' 'diversity,' 'family values,' 'freedom,' 'representation,' and so on. Set into each page like portholes or wormholes are two video monitors, without sound, that present a range of opinions in scrolling text, accompanied by a photo identifying each speaker as well as intermittent images, such as flames over landmark legal texts and once-banned books spinning across the screen, to dramatize the issues. At the center where the pages meet are the doors to the library, and the viewer finds on entering the book that the entire piece has been left behind, literally out on the street. There at least the insomniac could discover that this particular book never sleeps.

The title of the installation, according to the artists, "is a pun on the problems of library collections and, in a larger sense, on our society's own cultural reference and identity. In a library collection, acid migration is irreversible and leads to the complete destruction and deterioration of a book. It occurs when a material containing acid comes in contact with one containing less or no acid." The left and right video monitors, which are repeated in the facing page beyond the doorway, alternate statements that correspond roughly to left and right political viewpoints. The piece challenges its audience, by turning the private act of reading into a public project, to consider what is being said about censorship and the arts. But the implication is clear: it seems hard not to see the attacks by conservatives, particularly against the NEA, as shrill and paranoid; they, and not the artists, are the acid that could destroy the culture.

This section of the video is then followed by a second part, comprising responses from people in the arts to three questions: How would you define culture today? What is the role of art and artists in today's society? Should artists consider the public and the public's reaction when creating their artwork? A. B. Spellman, for instance, points out that "culture is more fluid than ever before," and he remarks that the categories of both identity and genre have become harder to define. Edward de Grazia would see this as a hopeful sign, since for him "the role of the artist is to rob us of the limits to our vision." The responses presented are kept to a few lines, but they show quite divergent attitudes even among figures of a similar political stripe. The book thus becomes a genuine reference work, by opening its very composition to a small multitude of voices.

Straightforward as it may seem, the piece occupies a curious position technically. The book itself is reduced to a matter of surfaces, where its nature as object is almost canceled out. What's more, the video component is also pared down, in that sound is dispensed with and the dominant image is a series of texts. Yet by layering the information in a visually compelling way, the book gains a certain dimension through the viewer's gaze. The passerby sees this unusual display and stops a moment to take it in. As he or she registers that it is a sort of dictionary, they notice the changing images and move closer to see what it says. Standing right next to it, one loses track of the mural---just as, from across the street, the video images seem only a blur but one is struck by the picture of this giant book. The full duration of the tape is about forty minutes, but since it is not dramatically structured like a movie and the season precludes loitering, a person is likely to read the book only in snippets---to browse, as it were. This does have its advantages: given the elements of the piece, its impact is immediate; one doesn't really need to watch the whole thing. Still, if a person passes by there repeatedly, they are offered the prospect of finding the book always at a different moment. In a sense, the book turns its own pages.

The issues at stake in this work recall the two previous video books by Ligorano/Reese, which employ the medium of television through more familiar routes. The Bible Belt (1992-93) reflects the slick hard-sell approach of televangelists but taken to extremes. The piece consists of an open Bible mounted on a wide leather belt with a large gold-plated buckle that says Jesus. Cut into the middle of the chapter "Proverbs," the video monitor shows a salesman hawking the Bible Belt as an affirmation of traditional values. The sales spot seems genuine with its requisite zeal, but gradually it becomes clear that actors are involved. However, this video segment alternates as though by channel surfing with other material taken directly from television, where excerpts of real televangelists are followed by glimpses of scrambled porn: the juxtaposition of this material produces a disturbing logic, as to suggest that the marketing of desire is really a clever shell game. Displayed in a gallery, the Bible Belt sits on a pedestal in the middle of the room surrounded by a number of such belts, in the version without video monitor, hung along the walls. In the words of the artists, the work "alludes to the wagon train of family values encircling the body politic."

As a book, the Bible is rendered almost irrelevant by the piece. What counts is its presentation, converted into a strange article of clothing like a fanny pack, as well as its representation---in the hands of such preachers it might sooner be snake oil. But what does it mean to wear a book, to wear it in good health? Does it become transformed, or even diminished, when subordinated to a function? The way the Bible Belt is constructed, the book that looms as founding text watches out for the rear; at any rate, the person who wears it cannot read it, though they smile in blank satisfaction as shown by the happy family modeling the belt in the video. By putting it on, they seem only to invite the unwelcome intruder to hover too closely in a frustrated effort to follow the word.

On a more quotidian level, the first video book by Ligorano/ Reese also treated the deceptions of the word, in that it tracked the manipulations of the mass media at the time of the Persian Gulf War. Breakfast of Champions (1991) portrays a typical American scene with ironic grandeur. Here the text as prop is a newspaper rather than a book---the New York Times---whose composite headlines trace the military and economic buoyancy of the moment. Laid upon a square breakfast table, it is surrounded by a bright array of other props: a placemat and coffee mug emblazoned with American flags, a slice of toast with a yellow patty of butter, a small vase of yellow flowers, a yellow folding chair, and above it all hangs a huge, ominous yellow ribbon. Cut into the paper, like another news photo, a video monitor offers a frightening blitz of non-information. The video begins with George Bush's "kinder, gentler" Presidential ad from 1988, following him amid a backdrop of surrendering prisoners of war, explosions, tanks, and paratroopers. Gradually, through a sampling of TV news coverage from the Gulf War, the screen itself seems to explode into many little screens. Thousands of disjointed fragments in effect cut up the military's press conferences, to show that this veneer of journalistic realism is really all form and no content.

If reading a daily newspaper, according to Marshall McLuhan, is "like taking a warm bath," the empty news concentrated in this installation accumulates with chilling effect. Everything seems dead here, even the generals talking on like machines---the butter will never melt on the toast, the leftover coffee will not be drunk, the newspaper will continue to fade and there is no point in turning the pages for nothing will change. It reminds us that, contrary to the sunny scene depicted, yellow is also the color of illness and of death. Ligorano/Reese show that what is missing in these pictures is a sense of dialogue, the free flow of information and ideas. And that is precisely what brings their latest work alive.

* * *

_

The Book Talks Back: the video books of Ligorano/Reese

published in Felix (New York) 2:1 (1995)

Despite their apparent similarity in form, the artist's book turns out to be quite a different animal than the literary artifact. The book that is mass produced serves a functional role---to make money ultimately or to win converts--- but it may be said as well of the loftier products of literature that they all play down the cover for what is inside. Whatever aesthetic considerations go into the design, it remains subordinate to the book's content. The artist's book, by contrast, radically alters this relationship.

Often presented as a unique object, and so distinguished from the infinitely reproducible text where only copies exist which can be owned by everyone, the artist's book draws attention to the mixed media of its construction. Even when it may be touched, its pages turned, it poses its own conditions in terms of reading. These conditions, however, only apply to that singular object, according to its blend of visual and sculptural elements, and its use of forms of writing, as well as the position it occupies with regard to the viewer. Text here may be largely de-emphasized or even absent, yet to read this book sets up a fruitful tension with our more usual habits of reading.

The video books of Nora Ligorano and Marshall Reese complicate this process by incorporating the most popular medium of our time, the moving image. Cut into the space of the page, a screen is placed which in effect screens out the text around it. The book becomes more like a theatrical object, the frame for the artists' strategy, or the proscenium arch itself, and the whole apparatus plays upon that central enchantment which looks strangely like television. But here the language of television is turned inside out to reveal the artifice of its illusion.

Amid their other activities as artists, Ligorano/Reese have produced three video books to date and each tackles issues in the ongoing cultural debate in the United States. Their latest work, Acid Migration of Culture (1994), stands as their most ambitious yet and also their most public. A large and elaborate installation, throughout the month of January it occupied the main windows of the Donnell Library, the branch of the New York Public Library directly across from the Museum of Modern Art. The piece concerns the hot topic of censorship and the arts and includes statements from about fifty artists, critics, politicians, and religious leaders. The frame in this case is a 45-foot long photo mural that shows the open pages of a dictionary which, in fact, was composed on a computer, since the words defined on these two pages cover the entire alphabet: terms such as 'art,' 'blasphemy,' 'civilization,' 'diversity,' 'family values,' 'freedom,' 'representation,' and so on. Set into each page like portholes or wormholes are two video monitors, without sound, that present a range of opinions in scrolling text, accompanied by a photo identifying each speaker as well as intermittent images, such as flames over landmark legal texts and once-banned books spinning across the screen, to dramatize the issues. At the center where the pages meet are the doors to the library, and the viewer finds on entering the book that the entire piece has been left behind, literally out on the street. There at least the insomniac could discover that this particular book never sleeps.

The title of the installation, according to the artists, "is a pun on the problems of library collections and, in a larger sense, on our society's own cultural reference and identity. In a library collection, acid migration is irreversible and leads to the complete destruction and deterioration of a book. It occurs when a material containing acid comes in contact with one containing less or no acid." The left and right video monitors, which are repeated in the facing page beyond the doorway, alternate statements that correspond roughly to left and right political viewpoints. The piece challenges its audience, by turning the private act of reading into a public project, to consider what is being said about censorship and the arts. But the implication is clear: it seems hard not to see the attacks by conservatives, particularly against the NEA, as shrill and paranoid; they, and not the artists, are the acid that could destroy the culture.

This section of the video is then followed by a second part, comprising responses from people in the arts to three questions: How would you define culture today? What is the role of art and artists in today's society? Should artists consider the public and the public's reaction when creating their artwork? A. B. Spellman, for instance, points out that "culture is more fluid than ever before," and he remarks that the categories of both identity and genre have become harder to define. Edward de Grazia would see this as a hopeful sign, since for him "the role of the artist is to rob us of the limits to our vision." The responses presented are kept to a few lines, but they show quite divergent attitudes even among figures of a similar political stripe. The book thus becomes a genuine reference work, by opening its very composition to a small multitude of voices.

Straightforward as it may seem, the piece occupies a curious position technically. The book itself is reduced to a matter of surfaces, where its nature as object is almost canceled out. What's more, the video component is also pared down, in that sound is dispensed with and the dominant image is a series of texts. Yet by layering the information in a visually compelling way, the book gains a certain dimension through the viewer's gaze. The passerby sees this unusual display and stops a moment to take it in. As he or she registers that it is a sort of dictionary, they notice the changing images and move closer to see what it says. Standing right next to it, one loses track of the mural---just as, from across the street, the video images seem only a blur but one is struck by the picture of this giant book. The full duration of the tape is about forty minutes, but since it is not dramatically structured like a movie and the season precludes loitering, a person is likely to read the book only in snippets---to browse, as it were. This does have its advantages: given the elements of the piece, its impact is immediate; one doesn't really need to watch the whole thing. Still, if a person passes by there repeatedly, they are offered the prospect of finding the book always at a different moment. In a sense, the book turns its own pages.

The issues at stake in this work recall the two previous video books by Ligorano/Reese, which employ the medium of television through more familiar routes. The Bible Belt (1992-93) reflects the slick hard-sell approach of televangelists but taken to extremes. The piece consists of an open Bible mounted on a wide leather belt with a large gold-plated buckle that says Jesus. Cut into the middle of the chapter "Proverbs," the video monitor shows a salesman hawking the Bible Belt as an affirmation of traditional values. The sales spot seems genuine with its requisite zeal, but gradually it becomes clear that actors are involved. However, this video segment alternates as though by channel surfing with other material taken directly from television, where excerpts of real televangelists are followed by glimpses of scrambled porn: the juxtaposition of this material produces a disturbing logic, as to suggest that the marketing of desire is really a clever shell game. Displayed in a gallery, the Bible Belt sits on a pedestal in the middle of the room surrounded by a number of such belts, in the version without video monitor, hung along the walls. In the words of the artists, the work "alludes to the wagon train of family values encircling the body politic."

As a book, the Bible is rendered almost irrelevant by the piece. What counts is its presentation, converted into a strange article of clothing like a fanny pack, as well as its representation---in the hands of such preachers it might sooner be snake oil. But what does it mean to wear a book, to wear it in good health? Does it become transformed, or even diminished, when subordinated to a function? The way the Bible Belt is constructed, the book that looms as founding text watches out for the rear; at any rate, the person who wears it cannot read it, though they smile in blank satisfaction as shown by the happy family modeling the belt in the video. By putting it on, they seem only to invite the unwelcome intruder to hover too closely in a frustrated effort to follow the word.

On a more quotidian level, the first video book by Ligorano/ Reese also treated the deceptions of the word, in that it tracked the manipulations of the mass media at the time of the Persian Gulf War. Breakfast of Champions (1991) portrays a typical American scene with ironic grandeur. Here the text as prop is a newspaper rather than a book---the New York Times---whose composite headlines trace the military and economic buoyancy of the moment. Laid upon a square breakfast table, it is surrounded by a bright array of other props: a placemat and coffee mug emblazoned with American flags, a slice of toast with a yellow patty of butter, a small vase of yellow flowers, a yellow folding chair, and above it all hangs a huge, ominous yellow ribbon. Cut into the paper, like another news photo, a video monitor offers a frightening blitz of non-information. The video begins with George Bush's "kinder, gentler" Presidential ad from 1988, following him amid a backdrop of surrendering prisoners of war, explosions, tanks, and paratroopers. Gradually, through a sampling of TV news coverage from the Gulf War, the screen itself seems to explode into many little screens. Thousands of disjointed fragments in effect cut up the military's press conferences, to show that this veneer of journalistic realism is really all form and no content.

If reading a daily newspaper, according to Marshall McLuhan, is "like taking a warm bath," the empty news concentrated in this installation accumulates with chilling effect. Everything seems dead here, even the generals talking on like machines---the butter will never melt on the toast, the leftover coffee will not be drunk, the newspaper will continue to fade and there is no point in turning the pages for nothing will change. It reminds us that, contrary to the sunny scene depicted, yellow is also the color of illness and of death. Ligorano/Reese show that what is missing in these pictures is a sense of dialogue, the free flow of information and ideas. And that is precisely what brings their latest work alive.

* * *

_

_Ligorano/Reese with Gerrit Lansing, Turning Leaves of Mind

New York: Granary Books, 2003

published in ARTnews (New York) January 2004

There is a marvelous tension, in this artists' book about books, between the glory that was Spanish bookbinding and the wear and tear of time. Yet, time is also an agent in the construction of this book. Simply put, Turning Leaves of Mind began twenty years ago with Nora Ligorano’s photo documentation of 13th- to 17th-century books in Spanish archives. Then, a year ago, she and Marshall Reese---collaborators on video books, installations, limited-edition objects---cropped, manipulated, and ordered the photos to make them into more than documents. Stitched throughout the pages, brief lines and phrases by poet Gerrit Lansing speak to the enchantments of the book, to the persistence of reading even among ruins.

Each square page is like a window onto the ornate details, the exquisite moments of those ancient books---their richly worked bindings, the wavy heft of the pages, the breaks and stains, the slow decay. The intermittent text, meanwhile, rises from the pages, first as image then words, the colors of the letters emerging out of the picture. “The dead breed dizzy dreams,” notes the text. Indeed, though the unknown writers be long gone, the fantastic objects still remain. And though these in turn may fade, a new book blossoms forth from the rubble of the old.

New York: Granary Books, 2003

published in ARTnews (New York) January 2004

There is a marvelous tension, in this artists' book about books, between the glory that was Spanish bookbinding and the wear and tear of time. Yet, time is also an agent in the construction of this book. Simply put, Turning Leaves of Mind began twenty years ago with Nora Ligorano’s photo documentation of 13th- to 17th-century books in Spanish archives. Then, a year ago, she and Marshall Reese---collaborators on video books, installations, limited-edition objects---cropped, manipulated, and ordered the photos to make them into more than documents. Stitched throughout the pages, brief lines and phrases by poet Gerrit Lansing speak to the enchantments of the book, to the persistence of reading even among ruins.

Each square page is like a window onto the ornate details, the exquisite moments of those ancient books---their richly worked bindings, the wavy heft of the pages, the breaks and stains, the slow decay. The intermittent text, meanwhile, rises from the pages, first as image then words, the colors of the letters emerging out of the picture. “The dead breed dizzy dreams,” notes the text. Indeed, though the unknown writers be long gone, the fantastic objects still remain. And though these in turn may fade, a new book blossoms forth from the rubble of the old.