_

Old Wine, New Bottles

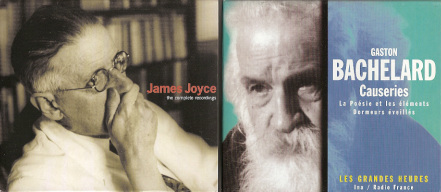

James Joyce, The Complete Recordings /

Eugene Jolas, James Joyce

Sub Rosa

CD/Book

Gaston Bachelard, Causeries

Radio France / INA

CD

published in American Book Review 26:2 (Jan.-Feb. 2005)

In 1924, two years after publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses under the imprint of her Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia Beach produced a recording of Joyce reading from his work. By arrangement with the company His Master’s Voice, which did not list the record in its catalogue, thirty copies were made at her expense. Subsequently, in 1929, Beach managed to have Joyce go to Cambridge to record the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section from what would become Finnegans Wake a decade later. These two occasions, under thirteen minutes all told, comprise his complete recordings.

Not surprisingly, the Joyce readings have been reissued several times. What distinguishes the current release, therefore, is the inclusion of the previously unpublished 80-page memoir of Joyce by his close friend Eugene Jolas, publisher of the seminal international vanguard journal transition (1927-1938), which often featured sections from Joyce’s then-called "Work in Progress." Written in the late 1940s, the memoir (edited by Marc Dachy) chronicles their growing friendship and the painstaking devotion with which Jolas and others around Joyce helped prepare for publication each complicated installment of his ultimate work, full of last-minute additions and corrections. It recalls the tenor and tone of many a private occasion among their families and friends, including Joyce’s anguish at the developing mental illness of his daughter Lucia. With a graceful touch in conveying Joyce’s spirit and how he lived those years of fertile turbulence, Jolas offers a singular glimpse of Finnegans Wake as a project elaborated over time.

As for the recordings, Joyce’s own voice is heard in two distinct modes. From late in the seventh episode (Aeolus) of Ulysses, he chose a speech that could be lifted nearly free of local reference to serve as a brief homily praising Moses in ancient Egypt for remaining steadfast in his faith before the arrogant Egyptian high priest and thus able to lead the captive Jews from bondage and to receive “the tables of the law, graven in the language of the outlaw.” Unfortunately, given that the original master was lost, this four-minute reading is difficult to hear above the surface noise of the source record, so it would have helped to have the printed text at hand. The speech, though, is intended as one professor’s critique of another who, like the high priest, would urge the youth of Ireland along a false path, and Joyce’s performance gathers force with comparable indignation as he too, in effect, lays claim to that language forged in exile.

The last pages of “Anna Livia Plurabelle,” by contrast, trip off Joyce’s tongue with such musical felicity that it is easy to forget that many of his words are invented, fusions of words from several languages or creative misspellings and conjugations based on oral delivery. Right off he launches into an enchanted rhythm: “Well, you know or don’t you kennet or haven’t I told you every telling has a taling . . .” Again, it’s too bad this release does not include the text; following his voice along the page not only facilitates the listening (though the sound quality is fairly clear), it also guides us as readers in approaching the book as a whole. That is, we are encouraged to read by ear, the better to navigate the fast currents between sense and sensibility. We understand the work better, experience it more fully, from having heard him read a part of it. In the long blocks of prose, his reading animates the web of voices, the mythic overtones, the spellbound force of night, drawing out the polyrhythms of consciousness until they almost infiltrate our own.

Gaston Bachelard, the French philosopher who wrote on the poetic imagination as well as the history of science, was born in 1884, two years after Joyce. Best known for The Poetics of Space (1957; translated by Maria Jolas), he gave many talks and interviews for French radio; over three dozen of these were recorded and preserved in the archives of the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA, which has in the past decade reissued CDs of Colette, André Breton, Marguerite Duras, J. M. G. Le Clézio, and many others; online catalogue at: www.ina.fr/produits/index.fr.html). Causeries (Talks), on two CDs, presents a series of seven lectures, “La poésie et les éléments” (Poetry and the Elements), from late 1952, and an extended discussion, “Dormeurs éveillés” (Wakeful Sleepers), from early 1954.

From the start of these talks, reflecting his books throughout the 1940s, Bachelard traces how the poetic imagination draws on the four material elements---water, fire, air, and earth---much in the way that philosophers and alchemists long based their cosmologies on those same elements. Citing various writers (Balzac, Shelley, Eluard, Melville), he explores the dynamic implications of each element’s nature and the accumulation of images they give rise to. Fire, for instance, as the very image of annihilation, may be seen as the terrain of death, but there is also the fire of purification and the fire in which the legendary phoenix is reborn; taking a psychoanalytic perspective, he also sketches a dialectic of fire and heat as divergent aspects of the same force. After laying out the respective imaginative qualities based on the four elements, he concludes with a discussion of human agency pertaining to them: the hand that works the different forms of matter, and the forge where the blacksmith makes use of all these elements to create new objects. “By transforming matter,” he reminds us, “we transform ourselves.”

In his lilting voice, full of enthusiasm for his vast subject, Bachelard transmits to the listener a sense of wonder that remains remarkably fresh after a lifetime of research and teaching. “Dormeurs éveillés” takes up a theme that grew out of his study of elemental poetics and dominated his late books, the state of reverie itself. In contrast to philosophy’s traditional inclination to “rethink thought,” as it were, he notes that “man is a being who not only thinks, but who first of all imagines, dreams.” Seeking to reconcile the diurnal and nocturnal realms of human experience, he draws on Novalis and Mallarmé to illustrate a certain consciousness of daydreaming or lucid dreaming, a way of being present in the world but not disturbed by it. Such reverie accomplishes a synthesis of reflection and imagination, at once reaching back into the depths of memory and ahead into an image of the possible. Just as the day, in his terms, becomes transcendence of the night, so the poet mines his or her silence and solitude to awaken into speech.

Old Wine, New Bottles

James Joyce, The Complete Recordings /

Eugene Jolas, James Joyce

Sub Rosa

CD/Book

Gaston Bachelard, Causeries

Radio France / INA

CD

published in American Book Review 26:2 (Jan.-Feb. 2005)

In 1924, two years after publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses under the imprint of her Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia Beach produced a recording of Joyce reading from his work. By arrangement with the company His Master’s Voice, which did not list the record in its catalogue, thirty copies were made at her expense. Subsequently, in 1929, Beach managed to have Joyce go to Cambridge to record the “Anna Livia Plurabelle” section from what would become Finnegans Wake a decade later. These two occasions, under thirteen minutes all told, comprise his complete recordings.

Not surprisingly, the Joyce readings have been reissued several times. What distinguishes the current release, therefore, is the inclusion of the previously unpublished 80-page memoir of Joyce by his close friend Eugene Jolas, publisher of the seminal international vanguard journal transition (1927-1938), which often featured sections from Joyce’s then-called "Work in Progress." Written in the late 1940s, the memoir (edited by Marc Dachy) chronicles their growing friendship and the painstaking devotion with which Jolas and others around Joyce helped prepare for publication each complicated installment of his ultimate work, full of last-minute additions and corrections. It recalls the tenor and tone of many a private occasion among their families and friends, including Joyce’s anguish at the developing mental illness of his daughter Lucia. With a graceful touch in conveying Joyce’s spirit and how he lived those years of fertile turbulence, Jolas offers a singular glimpse of Finnegans Wake as a project elaborated over time.

As for the recordings, Joyce’s own voice is heard in two distinct modes. From late in the seventh episode (Aeolus) of Ulysses, he chose a speech that could be lifted nearly free of local reference to serve as a brief homily praising Moses in ancient Egypt for remaining steadfast in his faith before the arrogant Egyptian high priest and thus able to lead the captive Jews from bondage and to receive “the tables of the law, graven in the language of the outlaw.” Unfortunately, given that the original master was lost, this four-minute reading is difficult to hear above the surface noise of the source record, so it would have helped to have the printed text at hand. The speech, though, is intended as one professor’s critique of another who, like the high priest, would urge the youth of Ireland along a false path, and Joyce’s performance gathers force with comparable indignation as he too, in effect, lays claim to that language forged in exile.

The last pages of “Anna Livia Plurabelle,” by contrast, trip off Joyce’s tongue with such musical felicity that it is easy to forget that many of his words are invented, fusions of words from several languages or creative misspellings and conjugations based on oral delivery. Right off he launches into an enchanted rhythm: “Well, you know or don’t you kennet or haven’t I told you every telling has a taling . . .” Again, it’s too bad this release does not include the text; following his voice along the page not only facilitates the listening (though the sound quality is fairly clear), it also guides us as readers in approaching the book as a whole. That is, we are encouraged to read by ear, the better to navigate the fast currents between sense and sensibility. We understand the work better, experience it more fully, from having heard him read a part of it. In the long blocks of prose, his reading animates the web of voices, the mythic overtones, the spellbound force of night, drawing out the polyrhythms of consciousness until they almost infiltrate our own.

Gaston Bachelard, the French philosopher who wrote on the poetic imagination as well as the history of science, was born in 1884, two years after Joyce. Best known for The Poetics of Space (1957; translated by Maria Jolas), he gave many talks and interviews for French radio; over three dozen of these were recorded and preserved in the archives of the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA, which has in the past decade reissued CDs of Colette, André Breton, Marguerite Duras, J. M. G. Le Clézio, and many others; online catalogue at: www.ina.fr/produits/index.fr.html). Causeries (Talks), on two CDs, presents a series of seven lectures, “La poésie et les éléments” (Poetry and the Elements), from late 1952, and an extended discussion, “Dormeurs éveillés” (Wakeful Sleepers), from early 1954.

From the start of these talks, reflecting his books throughout the 1940s, Bachelard traces how the poetic imagination draws on the four material elements---water, fire, air, and earth---much in the way that philosophers and alchemists long based their cosmologies on those same elements. Citing various writers (Balzac, Shelley, Eluard, Melville), he explores the dynamic implications of each element’s nature and the accumulation of images they give rise to. Fire, for instance, as the very image of annihilation, may be seen as the terrain of death, but there is also the fire of purification and the fire in which the legendary phoenix is reborn; taking a psychoanalytic perspective, he also sketches a dialectic of fire and heat as divergent aspects of the same force. After laying out the respective imaginative qualities based on the four elements, he concludes with a discussion of human agency pertaining to them: the hand that works the different forms of matter, and the forge where the blacksmith makes use of all these elements to create new objects. “By transforming matter,” he reminds us, “we transform ourselves.”

In his lilting voice, full of enthusiasm for his vast subject, Bachelard transmits to the listener a sense of wonder that remains remarkably fresh after a lifetime of research and teaching. “Dormeurs éveillés” takes up a theme that grew out of his study of elemental poetics and dominated his late books, the state of reverie itself. In contrast to philosophy’s traditional inclination to “rethink thought,” as it were, he notes that “man is a being who not only thinks, but who first of all imagines, dreams.” Seeking to reconcile the diurnal and nocturnal realms of human experience, he draws on Novalis and Mallarmé to illustrate a certain consciousness of daydreaming or lucid dreaming, a way of being present in the world but not disturbed by it. Such reverie accomplishes a synthesis of reflection and imagination, at once reaching back into the depths of memory and ahead into an image of the possible. Just as the day, in his terms, becomes transcendence of the night, so the poet mines his or her silence and solitude to awaken into speech.