_The ‘Total Theater’ of Renaud-Barrault

published in the International Herald Tribune (Paris), April 4-5, 1981

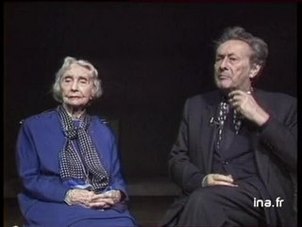

It is the same smile—the smile he wore as the lovesick mime Baptiste in the 1943 Marcel Carné-Jacques Prévert film Les enfants du paradis. Of all his roles, “I think Baptiste was the closest to me,” he says. In the fluency of his movement, yes. In the face of a man who hesitates, perhaps. But in the mime’s aching bursts into speech, hardly. Barrault is eloquent.

Through the vicissitudes of a long career, Jean-Louis Barrault, 70, has become almost synonymous with modern French theater. The veteran actor and director has revived the classics as well as introduced new works by avant-garde playwrights. Despite his age and what he calls his “fearful nature,” he still dares to risk his reputation by incorporating dance, film, mime, and music in new productions.

The tireless Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, which he founded with his wife Madeleine Renaud, has just made its ninth move. Last week, he opened this year’s season at a new location, the Théâtre du Rond-Point, with L’amour de l’amour, a charming adaptation of the Psyche myth, “an innocent play, a hymn of love to life, an apology for pleasure.”

The small theater, once the Palais de Glace, is just across the Champs-Elysées from the Théâtre de Marigny, where the company started 33 years ago. Barrault has high hopes for it: “We want to leave something alive of an international stature. All people of the theater in the world shall have their address there.”

Barrault’s career began 50 years ago when, “out of desperation,” he wrote a letter to the actor Charles Dullin, asking for an interview to study with him. Later that year, on his 21st birthday, he won his first role: a bit part as a servant in Ben Jonson’s Volpone, one of Dullin’s great successes.

Though he did not earn much money, he recalls in his autobiography, Souvenirs pour demain (Memories for Tomorrow), “with the complicity of my teacher” he began to live at Dullin’s theater, L’Atelier (stil in use in Montmartre). By 1935, he directed his first work, an adaptation of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. It was the first test of his notion of a “total theater” involving mime, masks, and Etienne Decroux’s “art of gesture.”

In the play, Barrault played a bastard who must ride alongside his mother’s funeral procession. “Being at once man and horse tempted me,” he recalls. “I wanted the actor to be a complete instrument, able to suggest both animal and horseman, Being and Space.”

Two days before the opening, the actress playing the mother disappeared. Barrault gathered his dispirited actors and declared, “I’ll play the mother, too.” In fact, by changing three scenes, he was able to play both roles.

“My idea, by necessity,” he says, “was to make the mother a totem.” Equipped with a mask and a wig, the mother figure could be “suggested” until animated by the actor in the spoken scenes. The experiment worked, and the play went on to become a triumph.

“I felt that in choosing theater, I was enrolling in the School of Life,” recalls Barrault.

After several years—and a few film roles—he left Dullin to improvise weekly “performances” with his Surrealist friends in a large loft on the rue des Grands-Augustins where Picasso later painted Guérnica. In the cultural ferment of the late 1930s, he writes, “anarchic generosity was the rule.”

He says he learned from the wayward genius Antonin Artaud “the metaphysics of theater”: how the actor, through his body and breathing, through the use of silence and of the present moment, becomes a sort of field of magnetic energy. It’s reflected in one of Barrault’s favorite mottos: “To be passionate about everything and attached to nothing.”

In 1940, Jacques Copeau asked Barrault to join the Comédie Française as both actor and director. He played Hamlet and directed Racine’s Phèdre. He soon became a life member, augmenting the company’s repertoire with such works as Le soulier de satin, the theatrical summit of his mentor, the French Catholic poet Paul Claudel. He stayed there throughout the war, but when the government forced changes on the company, he left it with Madeleine Renaud, a leading actress of the Comédie Française whom director Roger Blin has described as “having the greatest voice in the French theater.”

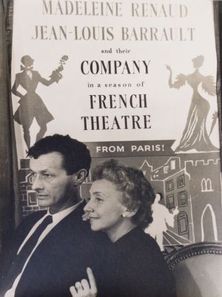

In 1947, they formed La Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, a private repertory troupe, to do experimental productions—the realization of a lifelong dream. From the earliest days, the troupe toured the world over—a total of more than 400,000 miles, says Barrault.

Among the early triumphs was the first dramatization of Kafka ever, the Barrault-Gide adaptation of The Trial. From the late 1940s, he began to collaborate with the leading artists, musicians, and set designers of his day. Musical scores were contributed by Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, and by the 20-year-old Pierre Boulez; decor and costumes by André Masson, Ernst, Cocteau, Dior, and Christian Bérard. When Barrault, casting for a pantomime, chose Marcel Marceau over a future collaborator, Maurice Béjart, Barrault says it changed Béjart’s career.

The troupe entered a new phase in 1959. A friend invited Barrault to a luncheon at which André Malraux, Gen. de Gaulle’s minister of Cultural Affairs, turned to his neighbor Madeleine Renaud and asked: “And now, chère madame, when are you moving into the Odéon?” Renaud replied: “But . . . whenever you like, monsieur le Ministre.” Malraux, says Barrault, had “nationalized our company.”

Now called the Théâtre de France, Barrault’s company produced new works by Beckett, Ionesco, Genet, Marguerite Duras, and Nathalie Sarraute, along with the classics. The plays were put on in the Odéon, an 18th-century edifice built for the Comédie Française, and a new center for theater research headed by Peter Brook was opened across town.

Then, one night in May 1968, a crowd of students took over the theater, calling it an “emblem of bourgeois culture.” Informed of the event, Malraux’s office told Barrault “to keep the dialogue open” and he tried. Finally, on the second night, he told them: “Barrault is dead, but a living being remains before you. What are we to do?” The students applauded him but didn’t leave for days. Malraux was furious. After three months of silence, he dismissed Barrault from the Odéon, and his company was left homeless.

But Barrault believes in the need “to convert fate into providence”—(he recalls his mother’s dying words: “If you knew. It’s marvelous!”) and he went right back to work on independent productions. Five months later, he put on a Rabelais play in an old wrestling arena in Montmartre.

Its rollicking success encouraged Barrault to try an unconventional piece based on the work and life of Alfred Jarry, the anarchic predecessor of both the Surrealists and the Theater of the Absurd. “I wanted,” he says, “to show that young people shouldn’t limit themselves by over-intellectualizing, and to see in Jarry that there were things absolutely whole and yet disturbing. And that drives people crazy.”

In 1974, the company had the opportunity to create a theater out of an abandoned Paris railroad station, the Gare d’Orsay, where it stayed until last year. “The construction of the theater,” says Barrault, “was the synthesis of our observations in all those years and on our tours.” It was spacious but intimate. Among their most popular producitons: a stage adaptation of the Colin Higgins story, Harold and Maude, with Madeleine Renaud as Maude.

Looking back over his career, Barrault says: “One of my best memories in theater was when we played Rabelais at the University of California at Berkeley. We were to give five performances in a 2,500-seat auditorium. After the fourth, the chancellor closed the campus due to a students’ battle with the police after the Kent State killings. So, our fifth performance was forbidden.

“The student and police delegations met and decided on a truce of four hours, to ‘allow Rabelais to express himself.’ Soon, all the doors were open, even to the police. We played to 4,000 people. And at the moment when everyone cries out, ‘Do what you will, for man is free!’ we improvised by putting on Berkeley T-shirts. It was a unique moment—the victory of the spirit, the supremacy of human intelligence. The human heart ignited like a fuse!

“The theatrical life has taught us that one cannot always be wise,” Barrault concludes. “There is always a coefficient of folly that must be respected.”

published in the International Herald Tribune (Paris), April 4-5, 1981

It is the same smile—the smile he wore as the lovesick mime Baptiste in the 1943 Marcel Carné-Jacques Prévert film Les enfants du paradis. Of all his roles, “I think Baptiste was the closest to me,” he says. In the fluency of his movement, yes. In the face of a man who hesitates, perhaps. But in the mime’s aching bursts into speech, hardly. Barrault is eloquent.

Through the vicissitudes of a long career, Jean-Louis Barrault, 70, has become almost synonymous with modern French theater. The veteran actor and director has revived the classics as well as introduced new works by avant-garde playwrights. Despite his age and what he calls his “fearful nature,” he still dares to risk his reputation by incorporating dance, film, mime, and music in new productions.

The tireless Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, which he founded with his wife Madeleine Renaud, has just made its ninth move. Last week, he opened this year’s season at a new location, the Théâtre du Rond-Point, with L’amour de l’amour, a charming adaptation of the Psyche myth, “an innocent play, a hymn of love to life, an apology for pleasure.”

The small theater, once the Palais de Glace, is just across the Champs-Elysées from the Théâtre de Marigny, where the company started 33 years ago. Barrault has high hopes for it: “We want to leave something alive of an international stature. All people of the theater in the world shall have their address there.”

Barrault’s career began 50 years ago when, “out of desperation,” he wrote a letter to the actor Charles Dullin, asking for an interview to study with him. Later that year, on his 21st birthday, he won his first role: a bit part as a servant in Ben Jonson’s Volpone, one of Dullin’s great successes.

Though he did not earn much money, he recalls in his autobiography, Souvenirs pour demain (Memories for Tomorrow), “with the complicity of my teacher” he began to live at Dullin’s theater, L’Atelier (stil in use in Montmartre). By 1935, he directed his first work, an adaptation of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. It was the first test of his notion of a “total theater” involving mime, masks, and Etienne Decroux’s “art of gesture.”

In the play, Barrault played a bastard who must ride alongside his mother’s funeral procession. “Being at once man and horse tempted me,” he recalls. “I wanted the actor to be a complete instrument, able to suggest both animal and horseman, Being and Space.”

Two days before the opening, the actress playing the mother disappeared. Barrault gathered his dispirited actors and declared, “I’ll play the mother, too.” In fact, by changing three scenes, he was able to play both roles.

“My idea, by necessity,” he says, “was to make the mother a totem.” Equipped with a mask and a wig, the mother figure could be “suggested” until animated by the actor in the spoken scenes. The experiment worked, and the play went on to become a triumph.

“I felt that in choosing theater, I was enrolling in the School of Life,” recalls Barrault.

After several years—and a few film roles—he left Dullin to improvise weekly “performances” with his Surrealist friends in a large loft on the rue des Grands-Augustins where Picasso later painted Guérnica. In the cultural ferment of the late 1930s, he writes, “anarchic generosity was the rule.”

He says he learned from the wayward genius Antonin Artaud “the metaphysics of theater”: how the actor, through his body and breathing, through the use of silence and of the present moment, becomes a sort of field of magnetic energy. It’s reflected in one of Barrault’s favorite mottos: “To be passionate about everything and attached to nothing.”

In 1940, Jacques Copeau asked Barrault to join the Comédie Française as both actor and director. He played Hamlet and directed Racine’s Phèdre. He soon became a life member, augmenting the company’s repertoire with such works as Le soulier de satin, the theatrical summit of his mentor, the French Catholic poet Paul Claudel. He stayed there throughout the war, but when the government forced changes on the company, he left it with Madeleine Renaud, a leading actress of the Comédie Française whom director Roger Blin has described as “having the greatest voice in the French theater.”

In 1947, they formed La Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, a private repertory troupe, to do experimental productions—the realization of a lifelong dream. From the earliest days, the troupe toured the world over—a total of more than 400,000 miles, says Barrault.

Among the early triumphs was the first dramatization of Kafka ever, the Barrault-Gide adaptation of The Trial. From the late 1940s, he began to collaborate with the leading artists, musicians, and set designers of his day. Musical scores were contributed by Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, and by the 20-year-old Pierre Boulez; decor and costumes by André Masson, Ernst, Cocteau, Dior, and Christian Bérard. When Barrault, casting for a pantomime, chose Marcel Marceau over a future collaborator, Maurice Béjart, Barrault says it changed Béjart’s career.

The troupe entered a new phase in 1959. A friend invited Barrault to a luncheon at which André Malraux, Gen. de Gaulle’s minister of Cultural Affairs, turned to his neighbor Madeleine Renaud and asked: “And now, chère madame, when are you moving into the Odéon?” Renaud replied: “But . . . whenever you like, monsieur le Ministre.” Malraux, says Barrault, had “nationalized our company.”

Now called the Théâtre de France, Barrault’s company produced new works by Beckett, Ionesco, Genet, Marguerite Duras, and Nathalie Sarraute, along with the classics. The plays were put on in the Odéon, an 18th-century edifice built for the Comédie Française, and a new center for theater research headed by Peter Brook was opened across town.

Then, one night in May 1968, a crowd of students took over the theater, calling it an “emblem of bourgeois culture.” Informed of the event, Malraux’s office told Barrault “to keep the dialogue open” and he tried. Finally, on the second night, he told them: “Barrault is dead, but a living being remains before you. What are we to do?” The students applauded him but didn’t leave for days. Malraux was furious. After three months of silence, he dismissed Barrault from the Odéon, and his company was left homeless.

But Barrault believes in the need “to convert fate into providence”—(he recalls his mother’s dying words: “If you knew. It’s marvelous!”) and he went right back to work on independent productions. Five months later, he put on a Rabelais play in an old wrestling arena in Montmartre.

Its rollicking success encouraged Barrault to try an unconventional piece based on the work and life of Alfred Jarry, the anarchic predecessor of both the Surrealists and the Theater of the Absurd. “I wanted,” he says, “to show that young people shouldn’t limit themselves by over-intellectualizing, and to see in Jarry that there were things absolutely whole and yet disturbing. And that drives people crazy.”

In 1974, the company had the opportunity to create a theater out of an abandoned Paris railroad station, the Gare d’Orsay, where it stayed until last year. “The construction of the theater,” says Barrault, “was the synthesis of our observations in all those years and on our tours.” It was spacious but intimate. Among their most popular producitons: a stage adaptation of the Colin Higgins story, Harold and Maude, with Madeleine Renaud as Maude.

Looking back over his career, Barrault says: “One of my best memories in theater was when we played Rabelais at the University of California at Berkeley. We were to give five performances in a 2,500-seat auditorium. After the fourth, the chancellor closed the campus due to a students’ battle with the police after the Kent State killings. So, our fifth performance was forbidden.

“The student and police delegations met and decided on a truce of four hours, to ‘allow Rabelais to express himself.’ Soon, all the doors were open, even to the police. We played to 4,000 people. And at the moment when everyone cries out, ‘Do what you will, for man is free!’ we improvised by putting on Berkeley T-shirts. It was a unique moment—the victory of the spirit, the supremacy of human intelligence. The human heart ignited like a fuse!

“The theatrical life has taught us that one cannot always be wise,” Barrault concludes. “There is always a coefficient of folly that must be respected.”