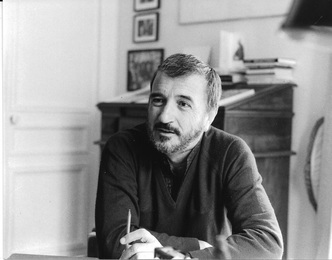

Jean-Claude Carrière

published in part in the International Herald Tribune (Paris) (July 1, 1983) and the Los Angeles Times (November 13, 1983), in full in Cinéaste (New York) XIII:1 (March 1983), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: Interviews in Paris with Uncommon Writers (Iowa City: Iowa, 1991)

Jean-Claude Carrière is probably best known as the screenwriter for nearly all of Luis Buñuel’s films since Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), including Belle de Jour (1967), The Milky Way (1968), The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), The Phantom of Liberty (1974), and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). That work alone would make him unique, but Carrière has also written for a host of other internationally prominent directors: Louis Malle (Viva Maria; The Thief of Paris), Jacques Deray (Borsalino), Milos Forman (Taking Off; Valmont), Volker Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum; Swann in Love), Andrzej Wajda (Danton; The Possessed), Carlos Saura (Antonieta), Philip Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being). He has had occasional small acting roles as well, especially in the Buñuel films. In addition, since the early 1970s he has worked regularly with theater director Peter Brook, a collaboration as important for him as that with Buñuel; working on every major Brook production, he has contributed new French adaptations of Shakespeare, Chekhov, a version of Attar’s epic, Conference of the Birds, and also of the monumental Indian epic, The Mahabharata.

In effect, Carrière is a translator of sorts. With a daring unmatched by others in his field, he has taken up complex visions and difficult works of literature, rendering them in theatrical terms that are notable for their resourcefulness. Above all, he is an ardent practitioner of the imagination. “The imagination must undergo an incessant training,” he insists. “You can’t let it sleep. In no case should it fall into intellectual comforts.” The following interview took place at his Paris home in early May 1983, before the English-language publication of Buñuel’s memoirs, My Last Sigh, in which Carrière’s role was essential (Buñuel died in late July of that year).

What was your part in Luis Buñuel's book of memoirs, My Last Sigh?

Through eighteen years of collaboration I’d been taking notes on his life, classing them by chapter. There’s a bit of everything. After That Obscure Object of Desire we worked on another script, “Une cérémonie somptueuse,” which is part of a phrase by André Breton about eroticism. We didn’t finish this script, Luis fell ill and he stopped doing cinema. That was in ‘79, and he began to get very bored. He was declaring that he was going to die, but that was four years ago, and he’s still alive. So, I took out these notes and said, “Let’s write a book, on you—your life, your ideas, your sensations.” Well, his first response was one of great refusal. He said, “No, what horror, an autobiography, every chambermaid writes her memoirs, everyone writes now. What horror, that, no, no, no!” So, I wrote by myself—in first person, and for me it was a very interesting exercise, to write while playing Buñuel—one of the book’s chapters, the one about bars, alcohol, and tobacco. The idea was to do a book like a scenario, taking his life as the subject. Because I told myself that could be really new, as a book of memoirs, that would be rather unconventional about one’s life, with interpolations like those we did in the films we made together. That is, we stop the life story and we tell a tale about something. About what’s important: God, death, women, wine, dreams, what’s really important for him. He read this chapter and he was very surprised, he said to me, “But I feel like I wrote it!” Because I’d done some research. Of course I know his vocabulary well, his way of speaking. I tried to identify him as if he really had written it.

Yes, I wondered if you had actually done the writing.

That’s one thing. Secondly, a few years ago a big Spanish paper from his part of the country, Aragon, had asked him to write something about his childhood, about his oldest memories. We were in the process of writing a script, That Obscure Object of Desire, and he said, ‘That annoys me, I don’t write, I don’t know how to write.” So I said, “Luis, if you like, we’ll stop the script for a day or two, you tell me about your childhood,” which I already knew about because he’d spoken a lot about his life to me, “and I’ll try to write it and you translate it into Spanish.” So, we did that, and the result was published, with the title moreover, “Medieval Memories of Lower Aragon.”

Well, we had these two documents, this thing which already existed and the chapter that I’d written. And these two things gave the book’s tone, one which was autobiographical and the other which was like an essay on something. So, then we set to work. I went to Mexico three times, for weeks at a stretch. In the morning, we worked at his house: I asked him questions, I took notes, he responded, we went deeper with one question or another. The afternoon and the evening, I wrote. I’d make photocopies in a little bookstore there, the next day I brought them to him, he read them over again. It was a lot of work, he edited, corrected, and so on. And it was a very uneven task, in certain cases there were chapters that were written all by myself, I almost didn’t need him because I had everything in my memory. Other chapters, like the one about the Spanish Civil War, for example, that was weeks worth of work. Because I told myself that for the first time in my life I would try to understand something about the Spanish Civil War. No one’s ever really understood anything, because all the accounts have always been from one side or another. They’ve always been very partial. So, with his incontestable authority in the Spanish world, where he is an immense figure, he could say what no Republican would have said, that Franco had helped to save the Jews, and that famous phrase about Franco: “I’m even ready to believe that he kept Spain out of World War II.” That phrase was like a bomb in Spain, that Buñuel who was of course anti-Franco during the war could say that today, that contributed to the national reconciliation in Spain, and to the success of the Socialists in the election, really. Considerably. That is, he was like the father long in exile who remains nevertheless a force in Spain. You know, Buñuel is clearly a greater man than Picasso. You have to go all the way back to Goya to find a figure of that importance. That is, Picasso is a great painter, but he’s only a painter. You can write books, make films, without ever thinking of Picasso. But whatever you do, in the Spanish world, whether you’re a novelist, painter, filmmaker of course, man of theater, at a given moment you’re going to meet up with Buñuel. He’s touched everything. He’s found some of the key images of the century in the Spanish world. In the United States, in France, in Italy, he’s considered a great filmmaker, and since his book as a great man. But with something marginal about it. They always say he’s a surrealist, he’s not really a classic, he’s not really a master of thought. In Spain, he’s not a surrealist at all, not at all. He is Spanish, period. What we find in him as bizarre, cruel, peculiar, in Spain is only natural.

When did you meet Buñuel?

Exactly twenty years ago. At the time he was looking for a young French screenwriter who knew the French countryside well. He’d worked a lot with the older French screenwriters, people were talking about the Nouvelle Vague then, he really wanted a young person. I’d done two films, that’s all, I was a beginner. I had gone to Cannes, and he was seeing various screenwriters there; I had lunch with him, we got along well, and three weeks later he chose me and I left for Madrid. Since then I haven’t stopped.

How did you two know you could work together?

It’s hard to say. Purely by instinct, I think. We discovered a lot of affinities. We’re both Mediterranean, that’s important, both Latin. I was born not far from the Spanish border. I had a Catholic education. I’m a wine producer. The first question he asked me when we sat down together at the table—and it’s not a light or frivolous question, the way he looked at me I sensed that it was a deep and important question—was, “Do you drink wine?” Just like that. That is, a negative response would have definitely disqualified me. So I said, “Not only do I drink wine, but I produce it. I’m from a family of vintners.” It’s true. Well, right away something quite rare had happened, to come upon a screenwriter who was a wine producer. And wine has been with us throughout these twenty years. We’ve tasted wine, talked about it, sung it. We’ve made some excellent meals. We’ve had more than two thousand meals together, through all that time. I figured that out the other day and I was very surprised. Many of them were here with friends who brought exceptional wines. I went to Mexico last week, I brought him wine, and cheese. So, that first question was followed by a thousand attempts at a response. Then there was the fact that I’d written books, of course. But it was an ideal sympathy. I’d liked him a lot for a long time, because at the age of eighteen I was already in charge of a film club at the university, and the films we knew then were his surrealist ones, the first three. After that, I was very stirred up at the age of twenty by Los Olvidados and El. And when I met him I’d just seen Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel. It was very important for us. Los Olvidados was a real shock. Imagine today, for a young man of twenty, in 1951, in the French cinema which was a bourgeois, artificial cinema, made in the studios, Jean Marais, Michèle Morgan, to receive Los Olvidados. It was an enormous shock, worth changing one’s life about. Certainly it’s one of the films that made me decide to write. The dream of the meat, in Los Olvidados, it’s an image from the Third World, the twentieth century. It’s a key image, a key to open that universe.

When did you start to write?

I was writing novels from the age of twenty-three or twenty-four. I’d even met Jacques Tati in 1956, I was twenty-five.

It was through Tati that you started in film?

I began by writing novels from two of his films, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Uncle. So, I was doing the opposite of what I was going to do so often later. I’d already written a novel, and then Tati had a contract with Robert Laffont, his publisher, who had a sort of little contest among his young writers and my chapter based on the film was chosen. Through that I met Pierre Etaix, with whom I wrote several projects. Then the Algerian War came along and I was called up, which lasted nearly three years, so it completely interrupted any sort of work. And on my return, I was thirty, I started right away to work on some film shorts with Etaix, in ‘61, and one of those won the Academy Award for Best Short Film. It was called Happy Anniversary, about a man who is bringing some flowers to his wife for their anniversary but gets caught in traffic jams. We made a feature film after that. And then I met Buñuel.

What was the most difficult for you to learn about writing film scripts?

Well, it’s always very difficult. If you want the work to have a chance of being interesting, escaping routine is an absolute necessity, to never say I know how to write a script. Each script must be the first one. Of course, experience does count for something, but no film that I’ve written resembles any other, I think. Each time I’ve tried, I still try, to find new ways, and I’ve worked with rather different people. Danton, with Wajda, for example, was quite serious, I’d never done a script with so much dialogue. Nor with a young actor (Gérard Depardieu) so lyrical, so determined, so tense. So, although previous experience does not count, secretly it does count all the same. I mean, if you rely consciously on your experience, to say, “I did it like that, so I know how to do it,” you run the biggest chance of going wrong. I’ve experienced that often enough. This sort of uncertainty is only acquired after a long series of setbacks, of choices made. It takes a lot of time, a lot of patience, and a lot of humility to arrive at this uncertainty.

Even so, you’ve had a lot of success with your scripts.

Yes, about one out of two. And in theater, about the same. That is, meeting Peter Brook was as decisive for me as meeting Luis. Moreover, our work has helped me a lot in screenwriting.

You also draw as well.

Amateur. I supported myself by drawing when I was a student and I continue to draw now and then. But I don’t really have the time for it. Drawing is like the piano, you have to do it three hours a day. If not, you don’t develop. Writing too is like that.

Has drawing helped you with the writing, in seeing how things might go?

Enormously. Almost every scenario I’ve worked on, I illustrated as well. For some it avoids long explanations, with the producers. For Belle de Jour, for example, I did at least twenty-five or thirty drawings, and the producers sold the film with that. And with Buñuel, he always asked me to illustrate the scripts. There are some that have been very elaborately illustrated. The Tin Drum, for example, with Schlöndorff, was very thoroughly illustrated, and the film is entirely faithful to that. In the design, the décor, the characters, the costumes. And besides, something very curious is proved. For example, we’re working on a scene, without saying anything about the décor. And then I decide we should talk about the image we have of the scene. I cover up the page and I ask Luis, say, “What side is the door on?” He’ll say, “The left.” “What side the lamp?” “The right.” Everything always coincides. It’s all so extraordinary, we find that we’ve been working with the same mental image of the scene.

In the manner of writing the script, has there been a big difference for you between adaptations from books and original stories?

Yes, it takes longer when it’s an adaptation. Because it always takes a good while, several weeks, before you’re completely free of a book. You’re always somewhat of a prisoner to the book, from the point of view of the script. Since if an author put something in that we want to omit, still he did have his reasons. So perhaps we should think about it, examine it, as much as we can, and that takes a lot of time. Out of the six films I did with Luis, three were from books, though That Obscure Object of Desire was very far from the book.

What do the new images come out of?

That’s a mystery. It’s an instinctive springing forth of images. That is, it’s not thought out. And each of us has the right of veto with the other. So, on the one hand these images arise from the free play of the material, and on the other hand they don’t really come from us. And if you ask me to explain, I can’t. I don’t know why these images, which apparently spring from the disorder of the spirit, become ordered when they enter into play, by which I mean the drama. You have to play a scene, and then you can write it. The simple fact of playing introduces an order, the dramatic action will inevitably follow from that moment. It begins with saying, “Here’s a place with this or that image,” I am introducing an order among the images that will arise. And the whole work of the scenario is born from this dialectic between the liberty, the phantom of liberty as Luis says in his film, and the order that proceeds from it, the dramatic order, which is implacable and won’t put up with just anything. Or it wouldn’t make any sense. That is the great mystery we’ve been confronted with daily for some time now, without ever theorizing about the scenario. I’m not a theoretician. What I’m telling you now I never talk about.

You’ve said that psychology doesn’t interest you with respect to characterization.

I’ll tell you why. Because the psychology on which traditional bourgeois theater relies supposes that we know the character before the story has ever begun. So, farewell to the free play of the imagination. If you’re a character that I have defined psychologically, in a completely arbitrary way, at that moment my imagination is paralyzed. I wouldn’t be able to make you do anything that’s going to go against that image. So, for the initial stage of work especially, psychology is enemy number one. Because it paralyzes and limits. And as Luis is fundamentally surrealist, it’s the irrational and not the rational that leads the way.

Though in other work you’ve had to approach a bit closer to the psychological, as in Carlos Saura’s Antonieta.

When I speak about psychology like that, I’m talking about with Buñuel. For other subjects without doubt it’s indispensable to follow a certain line of a character. The problem with Antonieta is entirely different, because she’s a true character who really lived, so I can’t invent.

How did you choose the subjects in the Buñuel films that were not adaptations? What determined the action?

Well, we never really chose a subject, in reality everything is the subject. Though The Milky Way, no, we did have a subject, we had a word: heresy. So, I had to find out all I could about the heresies, and then we created a subject, but the subject remains indefinite. As for The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, we never really chose a subject. That is, we speak about everything and nothing. About the same things as in The Milky Way really, but in another way. There the process of writing was completely different. I’d said to him, “There are things in your films that you repeat.” He said, “Yes, I like that. I’d like to do a story that repeats.” So, we chose that as a theme of discussion, you know that’s very vague. We started with a story about a crime where the criminal escapes, the crime is reconstituted. We worked two weeks and didn’t like it. And then completely by chance, we came upon this idea one day of a meal, about these friends who want to get together for dinner. We worked on it for two years on and off. Because it was very difficult to work without a subject, the danger was either we were making a completely gratuitous, surrealistic film that would be “improbable,” or else on the other hand a film that would be just flatly realistic. So, between the two, we chose the path of what is probable, but just at the limit of the probable, at the borderline. That’s what interested me, but that is very difficult to maintain.

How did The Phantom of Liberty come about? How did you proceed?

When we got together after The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, which was a big success at Cannes, we wondered, “Now what are we going to do?” We couldn’t just make another popular film. We started talking about liberty, and the title came from the end of The Discreet Charm, about the phantom of liberty. There was a principle to the tale. We asked ourselves why, when one tells a story, one tells this and not that? By what arbitrariness does one decide to tell what story? And we decided, we really don’t know. Because it’s that, the phantom of liberty, deciding what a film passes through. So, we imagine a couple who’s awaiting a very important telegram that’s going to decide the course of their lives. Their thoughts are only on the telegram. The telegram carrier rings, they take the telegram and close the door, and we stay on the carrier and follow him, leaving the couple behind. Naturally, that’s the contrary of what one expects.

And each time the film follows the person who’s arrived.

That’s right. Whoever interrupts the action, and we follow him because perhaps he has a story to tell, we’re going to see. That’s a principle which I think has never been used elsewhere. We were just speaking about an order that you have to find in the disorder, but there it had to do with a great disorder that we were forced to follow through to the end. In my opinion it’s one of Buñuel’s favorites of his films. At any rate, there are three or four scenes that are among his best, such as the little girl who is lost but who is there. But it’s a film that for certain people remained unpardonable, because it goes against all story conventions. He’d truly opened a surprising door. Like in his last film, in entrusting two actresses with a single role, that’s yet another door. So, up to the age of seventy-seven, Luis continued to open doors. Perhaps one day someone will come along and enter them.

What about the last script you were working on for him, “Une cérémonie somptueuse”?

There was a key word: terror. It told about a young woman terrorist who’s sentenced to years in prison. But this prison was also the place where her dreams, her images, gathered. That is, the doors of her prison could never close on the world. But I never finished it.

How did you get involved with the Proust film, Swann in Love, that’s being made now?

Peter Brook and Nicole Stéphane, who holds the rights, asked if I’d be interested in working on a film of Proust. I said yes, on the condition that we limit ourselves to the part without Proust. That is, where the narrator isn’t there, Swann in Love. Because we felt it would be extremely difficult to represent Marcel, and the whole work, adequately in a film. So, starting from there, we worked long and hard, saying that in doing Swann in Love we should extend the story of Swann until his death, and we’ve included many things from the ensemble of the work. We did a very careful study of the whole work and certain traits from it are found in the script. Because Proust, contrary to what people think, is a great realist, he tells you what everything looks like. But the film remains first of all a resume of twenty-four hours in Swann’s life. So, it’s about a man, Swann, who is very worldly and cultivated, and who is hit by love—by chance, like a cancer—and eventually dies from it.

Did you write the script alone?

With Peter Brook. And he was going to direct it originally, but then he didn’t have the time and Volker jumped in at that point.

Did the scripts from previous attempts at the project help at all, such as Pinter’s script?

I read three or four adaptations. Visconti’s is the one I prefer, but it was totally different. Like Pinter’s, it dealt with the whole work. But the part we’re doing neither Pinter nor Visconti dealt with, because the narrator isn’t there, it’s before the narrator’s time. Visconti’s script was very exciting, it focused on the Charlus story. As for Pinter, he tried to do an impressionistic summary of Proust’s work, without Swann. It’s a rather brilliant exercise.

Would you speak about your collaboration with Peter Brook and his theater at the Bouffes du Nord? What, for instance, was the nature of your adaptation of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard?

With Chekhov it was a problem of language. Chekhov’s language is really much like Beckett’s, with very strong, dense words, very alive. It’s not at all a bourgeois language of fashionable society, as in all the French and English translations. For example, a woman calls a man a kolossus, with a “k,” and in all the translations you will find, “Oh, he is a very intelligent man.” So, I worked with a Russian translator to do a new version.

I’ve been working with Peter for twelve years, though we’ve known each other for twenty. It’s very profound work, of course, very exciting, that serves as a base for us. We meet every day, it’s work that deals directly with the most essential. Peter is the opposite of someone who imposes his way, he searches with me. And he only finds what he’s after, moreover, in the last few days. Things are really not set in place until the last minute.

But what motivates the work of that searching?

There is no motive. Peter comes in with no plans. There’s just him, me, and the actors. He searches. It’s hard to admit, people always figure that we’re starting with some objective.

And so at what point do you write the texts then?

That depends. There’s no clean separation between the writing and the staging. That is, he participates in the writing and I in the staging, it’s like a “fade-out fade-in.”

There is a very ancient text from India that gives three rules for theater: 1) It must be encouraging and amusing to the drunk; 2) It must respond to the one who asks, “How to live?”; 3) It must respond to the one who asks, “How does the universe work?” All three at the same time. That’s ambitious!

published in part in the International Herald Tribune (Paris) (July 1, 1983) and the Los Angeles Times (November 13, 1983), in full in Cinéaste (New York) XIII:1 (March 1983), and subsequently in my book Writing at Risk: Interviews in Paris with Uncommon Writers (Iowa City: Iowa, 1991)

Jean-Claude Carrière is probably best known as the screenwriter for nearly all of Luis Buñuel’s films since Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), including Belle de Jour (1967), The Milky Way (1968), The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), The Phantom of Liberty (1974), and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). That work alone would make him unique, but Carrière has also written for a host of other internationally prominent directors: Louis Malle (Viva Maria; The Thief of Paris), Jacques Deray (Borsalino), Milos Forman (Taking Off; Valmont), Volker Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum; Swann in Love), Andrzej Wajda (Danton; The Possessed), Carlos Saura (Antonieta), Philip Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being). He has had occasional small acting roles as well, especially in the Buñuel films. In addition, since the early 1970s he has worked regularly with theater director Peter Brook, a collaboration as important for him as that with Buñuel; working on every major Brook production, he has contributed new French adaptations of Shakespeare, Chekhov, a version of Attar’s epic, Conference of the Birds, and also of the monumental Indian epic, The Mahabharata.

In effect, Carrière is a translator of sorts. With a daring unmatched by others in his field, he has taken up complex visions and difficult works of literature, rendering them in theatrical terms that are notable for their resourcefulness. Above all, he is an ardent practitioner of the imagination. “The imagination must undergo an incessant training,” he insists. “You can’t let it sleep. In no case should it fall into intellectual comforts.” The following interview took place at his Paris home in early May 1983, before the English-language publication of Buñuel’s memoirs, My Last Sigh, in which Carrière’s role was essential (Buñuel died in late July of that year).

What was your part in Luis Buñuel's book of memoirs, My Last Sigh?

Through eighteen years of collaboration I’d been taking notes on his life, classing them by chapter. There’s a bit of everything. After That Obscure Object of Desire we worked on another script, “Une cérémonie somptueuse,” which is part of a phrase by André Breton about eroticism. We didn’t finish this script, Luis fell ill and he stopped doing cinema. That was in ‘79, and he began to get very bored. He was declaring that he was going to die, but that was four years ago, and he’s still alive. So, I took out these notes and said, “Let’s write a book, on you—your life, your ideas, your sensations.” Well, his first response was one of great refusal. He said, “No, what horror, an autobiography, every chambermaid writes her memoirs, everyone writes now. What horror, that, no, no, no!” So, I wrote by myself—in first person, and for me it was a very interesting exercise, to write while playing Buñuel—one of the book’s chapters, the one about bars, alcohol, and tobacco. The idea was to do a book like a scenario, taking his life as the subject. Because I told myself that could be really new, as a book of memoirs, that would be rather unconventional about one’s life, with interpolations like those we did in the films we made together. That is, we stop the life story and we tell a tale about something. About what’s important: God, death, women, wine, dreams, what’s really important for him. He read this chapter and he was very surprised, he said to me, “But I feel like I wrote it!” Because I’d done some research. Of course I know his vocabulary well, his way of speaking. I tried to identify him as if he really had written it.

Yes, I wondered if you had actually done the writing.

That’s one thing. Secondly, a few years ago a big Spanish paper from his part of the country, Aragon, had asked him to write something about his childhood, about his oldest memories. We were in the process of writing a script, That Obscure Object of Desire, and he said, ‘That annoys me, I don’t write, I don’t know how to write.” So I said, “Luis, if you like, we’ll stop the script for a day or two, you tell me about your childhood,” which I already knew about because he’d spoken a lot about his life to me, “and I’ll try to write it and you translate it into Spanish.” So, we did that, and the result was published, with the title moreover, “Medieval Memories of Lower Aragon.”

Well, we had these two documents, this thing which already existed and the chapter that I’d written. And these two things gave the book’s tone, one which was autobiographical and the other which was like an essay on something. So, then we set to work. I went to Mexico three times, for weeks at a stretch. In the morning, we worked at his house: I asked him questions, I took notes, he responded, we went deeper with one question or another. The afternoon and the evening, I wrote. I’d make photocopies in a little bookstore there, the next day I brought them to him, he read them over again. It was a lot of work, he edited, corrected, and so on. And it was a very uneven task, in certain cases there were chapters that were written all by myself, I almost didn’t need him because I had everything in my memory. Other chapters, like the one about the Spanish Civil War, for example, that was weeks worth of work. Because I told myself that for the first time in my life I would try to understand something about the Spanish Civil War. No one’s ever really understood anything, because all the accounts have always been from one side or another. They’ve always been very partial. So, with his incontestable authority in the Spanish world, where he is an immense figure, he could say what no Republican would have said, that Franco had helped to save the Jews, and that famous phrase about Franco: “I’m even ready to believe that he kept Spain out of World War II.” That phrase was like a bomb in Spain, that Buñuel who was of course anti-Franco during the war could say that today, that contributed to the national reconciliation in Spain, and to the success of the Socialists in the election, really. Considerably. That is, he was like the father long in exile who remains nevertheless a force in Spain. You know, Buñuel is clearly a greater man than Picasso. You have to go all the way back to Goya to find a figure of that importance. That is, Picasso is a great painter, but he’s only a painter. You can write books, make films, without ever thinking of Picasso. But whatever you do, in the Spanish world, whether you’re a novelist, painter, filmmaker of course, man of theater, at a given moment you’re going to meet up with Buñuel. He’s touched everything. He’s found some of the key images of the century in the Spanish world. In the United States, in France, in Italy, he’s considered a great filmmaker, and since his book as a great man. But with something marginal about it. They always say he’s a surrealist, he’s not really a classic, he’s not really a master of thought. In Spain, he’s not a surrealist at all, not at all. He is Spanish, period. What we find in him as bizarre, cruel, peculiar, in Spain is only natural.

When did you meet Buñuel?

Exactly twenty years ago. At the time he was looking for a young French screenwriter who knew the French countryside well. He’d worked a lot with the older French screenwriters, people were talking about the Nouvelle Vague then, he really wanted a young person. I’d done two films, that’s all, I was a beginner. I had gone to Cannes, and he was seeing various screenwriters there; I had lunch with him, we got along well, and three weeks later he chose me and I left for Madrid. Since then I haven’t stopped.

How did you two know you could work together?

It’s hard to say. Purely by instinct, I think. We discovered a lot of affinities. We’re both Mediterranean, that’s important, both Latin. I was born not far from the Spanish border. I had a Catholic education. I’m a wine producer. The first question he asked me when we sat down together at the table—and it’s not a light or frivolous question, the way he looked at me I sensed that it was a deep and important question—was, “Do you drink wine?” Just like that. That is, a negative response would have definitely disqualified me. So I said, “Not only do I drink wine, but I produce it. I’m from a family of vintners.” It’s true. Well, right away something quite rare had happened, to come upon a screenwriter who was a wine producer. And wine has been with us throughout these twenty years. We’ve tasted wine, talked about it, sung it. We’ve made some excellent meals. We’ve had more than two thousand meals together, through all that time. I figured that out the other day and I was very surprised. Many of them were here with friends who brought exceptional wines. I went to Mexico last week, I brought him wine, and cheese. So, that first question was followed by a thousand attempts at a response. Then there was the fact that I’d written books, of course. But it was an ideal sympathy. I’d liked him a lot for a long time, because at the age of eighteen I was already in charge of a film club at the university, and the films we knew then were his surrealist ones, the first three. After that, I was very stirred up at the age of twenty by Los Olvidados and El. And when I met him I’d just seen Viridiana and The Exterminating Angel. It was very important for us. Los Olvidados was a real shock. Imagine today, for a young man of twenty, in 1951, in the French cinema which was a bourgeois, artificial cinema, made in the studios, Jean Marais, Michèle Morgan, to receive Los Olvidados. It was an enormous shock, worth changing one’s life about. Certainly it’s one of the films that made me decide to write. The dream of the meat, in Los Olvidados, it’s an image from the Third World, the twentieth century. It’s a key image, a key to open that universe.

When did you start to write?

I was writing novels from the age of twenty-three or twenty-four. I’d even met Jacques Tati in 1956, I was twenty-five.

It was through Tati that you started in film?

I began by writing novels from two of his films, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Uncle. So, I was doing the opposite of what I was going to do so often later. I’d already written a novel, and then Tati had a contract with Robert Laffont, his publisher, who had a sort of little contest among his young writers and my chapter based on the film was chosen. Through that I met Pierre Etaix, with whom I wrote several projects. Then the Algerian War came along and I was called up, which lasted nearly three years, so it completely interrupted any sort of work. And on my return, I was thirty, I started right away to work on some film shorts with Etaix, in ‘61, and one of those won the Academy Award for Best Short Film. It was called Happy Anniversary, about a man who is bringing some flowers to his wife for their anniversary but gets caught in traffic jams. We made a feature film after that. And then I met Buñuel.

What was the most difficult for you to learn about writing film scripts?

Well, it’s always very difficult. If you want the work to have a chance of being interesting, escaping routine is an absolute necessity, to never say I know how to write a script. Each script must be the first one. Of course, experience does count for something, but no film that I’ve written resembles any other, I think. Each time I’ve tried, I still try, to find new ways, and I’ve worked with rather different people. Danton, with Wajda, for example, was quite serious, I’d never done a script with so much dialogue. Nor with a young actor (Gérard Depardieu) so lyrical, so determined, so tense. So, although previous experience does not count, secretly it does count all the same. I mean, if you rely consciously on your experience, to say, “I did it like that, so I know how to do it,” you run the biggest chance of going wrong. I’ve experienced that often enough. This sort of uncertainty is only acquired after a long series of setbacks, of choices made. It takes a lot of time, a lot of patience, and a lot of humility to arrive at this uncertainty.

Even so, you’ve had a lot of success with your scripts.

Yes, about one out of two. And in theater, about the same. That is, meeting Peter Brook was as decisive for me as meeting Luis. Moreover, our work has helped me a lot in screenwriting.

You also draw as well.

Amateur. I supported myself by drawing when I was a student and I continue to draw now and then. But I don’t really have the time for it. Drawing is like the piano, you have to do it three hours a day. If not, you don’t develop. Writing too is like that.

Has drawing helped you with the writing, in seeing how things might go?

Enormously. Almost every scenario I’ve worked on, I illustrated as well. For some it avoids long explanations, with the producers. For Belle de Jour, for example, I did at least twenty-five or thirty drawings, and the producers sold the film with that. And with Buñuel, he always asked me to illustrate the scripts. There are some that have been very elaborately illustrated. The Tin Drum, for example, with Schlöndorff, was very thoroughly illustrated, and the film is entirely faithful to that. In the design, the décor, the characters, the costumes. And besides, something very curious is proved. For example, we’re working on a scene, without saying anything about the décor. And then I decide we should talk about the image we have of the scene. I cover up the page and I ask Luis, say, “What side is the door on?” He’ll say, “The left.” “What side the lamp?” “The right.” Everything always coincides. It’s all so extraordinary, we find that we’ve been working with the same mental image of the scene.

In the manner of writing the script, has there been a big difference for you between adaptations from books and original stories?

Yes, it takes longer when it’s an adaptation. Because it always takes a good while, several weeks, before you’re completely free of a book. You’re always somewhat of a prisoner to the book, from the point of view of the script. Since if an author put something in that we want to omit, still he did have his reasons. So perhaps we should think about it, examine it, as much as we can, and that takes a lot of time. Out of the six films I did with Luis, three were from books, though That Obscure Object of Desire was very far from the book.

What do the new images come out of?

That’s a mystery. It’s an instinctive springing forth of images. That is, it’s not thought out. And each of us has the right of veto with the other. So, on the one hand these images arise from the free play of the material, and on the other hand they don’t really come from us. And if you ask me to explain, I can’t. I don’t know why these images, which apparently spring from the disorder of the spirit, become ordered when they enter into play, by which I mean the drama. You have to play a scene, and then you can write it. The simple fact of playing introduces an order, the dramatic action will inevitably follow from that moment. It begins with saying, “Here’s a place with this or that image,” I am introducing an order among the images that will arise. And the whole work of the scenario is born from this dialectic between the liberty, the phantom of liberty as Luis says in his film, and the order that proceeds from it, the dramatic order, which is implacable and won’t put up with just anything. Or it wouldn’t make any sense. That is the great mystery we’ve been confronted with daily for some time now, without ever theorizing about the scenario. I’m not a theoretician. What I’m telling you now I never talk about.

You’ve said that psychology doesn’t interest you with respect to characterization.

I’ll tell you why. Because the psychology on which traditional bourgeois theater relies supposes that we know the character before the story has ever begun. So, farewell to the free play of the imagination. If you’re a character that I have defined psychologically, in a completely arbitrary way, at that moment my imagination is paralyzed. I wouldn’t be able to make you do anything that’s going to go against that image. So, for the initial stage of work especially, psychology is enemy number one. Because it paralyzes and limits. And as Luis is fundamentally surrealist, it’s the irrational and not the rational that leads the way.

Though in other work you’ve had to approach a bit closer to the psychological, as in Carlos Saura’s Antonieta.

When I speak about psychology like that, I’m talking about with Buñuel. For other subjects without doubt it’s indispensable to follow a certain line of a character. The problem with Antonieta is entirely different, because she’s a true character who really lived, so I can’t invent.

How did you choose the subjects in the Buñuel films that were not adaptations? What determined the action?

Well, we never really chose a subject, in reality everything is the subject. Though The Milky Way, no, we did have a subject, we had a word: heresy. So, I had to find out all I could about the heresies, and then we created a subject, but the subject remains indefinite. As for The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, we never really chose a subject. That is, we speak about everything and nothing. About the same things as in The Milky Way really, but in another way. There the process of writing was completely different. I’d said to him, “There are things in your films that you repeat.” He said, “Yes, I like that. I’d like to do a story that repeats.” So, we chose that as a theme of discussion, you know that’s very vague. We started with a story about a crime where the criminal escapes, the crime is reconstituted. We worked two weeks and didn’t like it. And then completely by chance, we came upon this idea one day of a meal, about these friends who want to get together for dinner. We worked on it for two years on and off. Because it was very difficult to work without a subject, the danger was either we were making a completely gratuitous, surrealistic film that would be “improbable,” or else on the other hand a film that would be just flatly realistic. So, between the two, we chose the path of what is probable, but just at the limit of the probable, at the borderline. That’s what interested me, but that is very difficult to maintain.

How did The Phantom of Liberty come about? How did you proceed?

When we got together after The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, which was a big success at Cannes, we wondered, “Now what are we going to do?” We couldn’t just make another popular film. We started talking about liberty, and the title came from the end of The Discreet Charm, about the phantom of liberty. There was a principle to the tale. We asked ourselves why, when one tells a story, one tells this and not that? By what arbitrariness does one decide to tell what story? And we decided, we really don’t know. Because it’s that, the phantom of liberty, deciding what a film passes through. So, we imagine a couple who’s awaiting a very important telegram that’s going to decide the course of their lives. Their thoughts are only on the telegram. The telegram carrier rings, they take the telegram and close the door, and we stay on the carrier and follow him, leaving the couple behind. Naturally, that’s the contrary of what one expects.

And each time the film follows the person who’s arrived.

That’s right. Whoever interrupts the action, and we follow him because perhaps he has a story to tell, we’re going to see. That’s a principle which I think has never been used elsewhere. We were just speaking about an order that you have to find in the disorder, but there it had to do with a great disorder that we were forced to follow through to the end. In my opinion it’s one of Buñuel’s favorites of his films. At any rate, there are three or four scenes that are among his best, such as the little girl who is lost but who is there. But it’s a film that for certain people remained unpardonable, because it goes against all story conventions. He’d truly opened a surprising door. Like in his last film, in entrusting two actresses with a single role, that’s yet another door. So, up to the age of seventy-seven, Luis continued to open doors. Perhaps one day someone will come along and enter them.

What about the last script you were working on for him, “Une cérémonie somptueuse”?

There was a key word: terror. It told about a young woman terrorist who’s sentenced to years in prison. But this prison was also the place where her dreams, her images, gathered. That is, the doors of her prison could never close on the world. But I never finished it.

How did you get involved with the Proust film, Swann in Love, that’s being made now?

Peter Brook and Nicole Stéphane, who holds the rights, asked if I’d be interested in working on a film of Proust. I said yes, on the condition that we limit ourselves to the part without Proust. That is, where the narrator isn’t there, Swann in Love. Because we felt it would be extremely difficult to represent Marcel, and the whole work, adequately in a film. So, starting from there, we worked long and hard, saying that in doing Swann in Love we should extend the story of Swann until his death, and we’ve included many things from the ensemble of the work. We did a very careful study of the whole work and certain traits from it are found in the script. Because Proust, contrary to what people think, is a great realist, he tells you what everything looks like. But the film remains first of all a resume of twenty-four hours in Swann’s life. So, it’s about a man, Swann, who is very worldly and cultivated, and who is hit by love—by chance, like a cancer—and eventually dies from it.

Did you write the script alone?

With Peter Brook. And he was going to direct it originally, but then he didn’t have the time and Volker jumped in at that point.

Did the scripts from previous attempts at the project help at all, such as Pinter’s script?

I read three or four adaptations. Visconti’s is the one I prefer, but it was totally different. Like Pinter’s, it dealt with the whole work. But the part we’re doing neither Pinter nor Visconti dealt with, because the narrator isn’t there, it’s before the narrator’s time. Visconti’s script was very exciting, it focused on the Charlus story. As for Pinter, he tried to do an impressionistic summary of Proust’s work, without Swann. It’s a rather brilliant exercise.

Would you speak about your collaboration with Peter Brook and his theater at the Bouffes du Nord? What, for instance, was the nature of your adaptation of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard?

With Chekhov it was a problem of language. Chekhov’s language is really much like Beckett’s, with very strong, dense words, very alive. It’s not at all a bourgeois language of fashionable society, as in all the French and English translations. For example, a woman calls a man a kolossus, with a “k,” and in all the translations you will find, “Oh, he is a very intelligent man.” So, I worked with a Russian translator to do a new version.

I’ve been working with Peter for twelve years, though we’ve known each other for twenty. It’s very profound work, of course, very exciting, that serves as a base for us. We meet every day, it’s work that deals directly with the most essential. Peter is the opposite of someone who imposes his way, he searches with me. And he only finds what he’s after, moreover, in the last few days. Things are really not set in place until the last minute.

But what motivates the work of that searching?

There is no motive. Peter comes in with no plans. There’s just him, me, and the actors. He searches. It’s hard to admit, people always figure that we’re starting with some objective.

And so at what point do you write the texts then?

That depends. There’s no clean separation between the writing and the staging. That is, he participates in the writing and I in the staging, it’s like a “fade-out fade-in.”

There is a very ancient text from India that gives three rules for theater: 1) It must be encouraging and amusing to the drunk; 2) It must respond to the one who asks, “How to live?”; 3) It must respond to the one who asks, “How does the universe work?” All three at the same time. That’s ambitious!