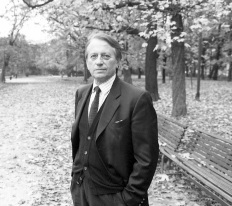

Hector Bianciotti

published in the Voice Literary Supplement (New York) May 1995, Hopscotch (Durham, NC) 1:4 (1999)_

Born in Córdoba, Argentina in 1930, Hector Bianciotti published his first novel, Los desiertos dorados (The Golden Deserts), in 1967. He wrote three more novels and a book of short stories in Spanish before switching to French with Sans la miséricorde du Christ (Without Christ's Mercy), which won the Prix Femina in 1985. Subsequently, he wrote several other novels, including Le pas si lent de l'amour (1995; So Slow the Pace of Love), which follows the autobiographical line taken up in Ce que la nuit raconte au jour (1992; What the Night Tells the Day, 1995). In 1996, he was inducted into the Académie Française.

The following interview took place at his home in Paris on June 23, 1994.

Why did you leave Argentina originally?

I left Argentina because it was a dream, a very Argentine dream, to leave. Because one way of being Argentine is in not wanting to be, at least in my day. After all, I'm first-generation, from an Italian family of farmers. My father sent the boys---not the girls, but the boys---to study in town for a year or two, according to how well the harvest had gone. One year he sent me, I was eleven, and when I came home for vacation I said that I was entering the seminary. It was just so I could study. I didn't like the country at all---when I was seven or eight, I used to tell my brothers who were working the land that they were idiots because they stayed there, they should get out. At that point I didn't even know cities, except from reading. So, my father was furious---my mother as well, contrary to what I expected---but finally they let me go.

How old were you at the time?

Twelve. And there, I read a lot. I told the rector I wanted to be cultivated, so I needed to read. The seminary was near Buenos Aires, he told me I could leave once a month and buy the books I wanted, he would give me some money, as long as I didn't lend them to my schoolmates. At the time, I used to think that the best books were those in the Church index. I started with a book that I can't read even today, Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. And Kierkegaard's Concept of Anxiety. They also gave me the literary supplements from the Sunday papers. And when I was fifteen I discovered---because he had died and there were a lot of special issues on him---Paul Valéry. The idea of pure poetry, the Variétés, the Méthode de Léonard de Vinci, and so on, for me it was all so dazzling---I still read Valéry, because the Cahiers, the notebooks, those four thousand pages in the Pléiades edition, are inexhaustible, it's like the Bible. You can open them anywhere, there's always something intelligent.

You still go back to them.

Still. And all that was related to France. Why France? First of all, because of Rubén Darío, who was the first poet I thought was an absolute genius. And then through the literary supplements I was reading, I understood that cultured people in Argentina looked only toward France. And that, thanks to Victoria Ocampo, we might aspire one day to be a cultured country. So, that's how I had the obsession about France, and to leave as soon as I could. And then, it was a horrible time, with the Perón dictatorship . . . But in fact I had several vocations. I was doing theater, for one thing. There was always the French theater season in Buenos Aires---one year, 1954, Barrault's company came and they were followed for the first time by Giorgio Strehler's Piccolo Teatro di Milano. That was rather interesting, because Italian culture in Argentina didn't exist, it was practically hidden---Italians were immigrants, poor people. I was dazzled by the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, and I asked Strehler where one could study directing. He said, There's only one school I know, and that's in Rome. Well, I was very discouraged, and one summer day sitting in a square I saw an Argentine poet coming along whom I barely knew, and strangely enough he stopped to tell me, "If you don't leave this country now, you are screwed forever!" I said, "How am I going to leave?" I didn't have a cent. So he said, "Oh, listen, your friends can help you, you'll manage, and there's a boat leaving for Italy in three weeks that isn't expensive." And that was that. My friends organized a show, and I left without money, with the equivalent today of a thousand francs. In Italy I went to the theater school, but I couldn't continue because I was starving. I don't know how I survived in Italy, always through friends who came from Paris or arrived from Argentina. Finally I turned up in Paris one day, at the Orly airport, where I arrived without a visa. Because I was escaping with a friend, from a rooming house in Salzburg where we hadn't paid, and he had taken a train. So I was arrested in the airport, and at four in the morning I managed to contact an Argentine friend of mine who was in Paris, and they got me out with a transit visa in order to go somewhere else. The only country where I might possibly earn a living was Spain, because during the show in Argentina a big Spanish film actor came by to see me, he gave me his card and said, "If you ever come to Spain and need to find work . . . " I went to Spain, afraid of a dictatorship that was even worse, I went to see him, he was starting a film, I started there.

As an actor.

As an actor. And I stayed in Spain, alas. It was dreadful, because the quality of the theater, the ignorance of people, because there was total censorship . . .

This was the late 1950s.

Yes. I arrived in Rome in April 1955, and I arrived the 30th or 31st of October, I think, in Madrid, the same year.

And when did you come to Paris?

I arrived here in February 1961. Because that Argentine friend who had saved my life in Paris, who had gotten me out of the airport, had meanwhile been Strehler's assistant, and he wanted to put on a play in Madrid. He had commissioned the set from Leonor Fini, and she was delighted with the work because I carried out all her plans and sketches for the set and the costumes. She came four days before the premiere. So, she offered me to be her assistant in Paris. I said yes right away. It was in Paris that I began to write novels in Spanish. But at the same time my very first job was as a reader at Gallimard, of Spanish and Italian literature. I had learned French starting with Valéry---by myself like that, comparing the original, with a dictionary. I was used to reading but I hadn't spoken or written. So I began with these reader's reports. I had to do a lot each week, I wrote for years and years, and in the meantime I published. By 1969 I had two books already translated into French---one hadn't even been published in Spanish yet. In 1969 my editor, Maurice Nadeau, who has the Quinzaine Littéraire, asked me to write an article. I started to write for the Quinzaine Littéraire in French. In 1972 the Nouvel Observateur asked me, and so I worked fourteen years for the Nouvel Observateur. I was trying to keep writing in Spanish, but after twenty years living in France I couldn't do it anymore. My Spanish had become uprooted.

You couldn't find the words sometimes?

It's not the words that count. We always find the words. But what's hard is the syntax. French syntax had destroyed the other. That's how I ended up writing a short story, the first story, in 1981. I had done a collection of stories, I had ten written in Spanish, I needed one more. I kept turning it over, and then one day I thought I'd found how the characters enter, and five lines were written in French. It had an expression there, a turn of phrase, that was typically French, "aussi loin qu'il m'en souvient." I told myself, If that expression came spontaneously, perhaps I should be writing in French. Since it's a short story, I'm going to try. And that was the moment I swung into French.

Once you arrived here, did you know you were going to stay?

Oh, yes! Completely. And I'll tell you, for example in Spain, the first experience of what happens when one changes language. You know, an Argentine's elocution has nothing to do with a Castillian elocution. To do theater, I had to try to speak like a Spaniard. One of my first experiences was, I was going along the street rehearsing the texts, and I realized that I was walking in another manner. I was holding my head another way, I stuck out my chest---like the Spaniards of Castille, they're always braving death. I didn't really feel comfortable. In France, on the other hand, I began to feel much more at ease, for many reasons. I found that French is an intimate language, which suits me much more as a sensibility than Spanish does. Also, there's something in France that didn't exist in the other European countries I know: that is, the perpetual sense of the critique. In fact, the French are less interested in art than in theory. I still think about what I read back in Argentina, it was Eliot on criticism, where he says that of two artists who have the same talent, the best is the one with the more developed critical sense. In France there is a lot of this, after all it is the country that invented the art of conversation in the 17th century. That is, the history of the reply. The reply which puts you on the alert---you have to listen, you have to try to respond.

When you first arrived, you didn't really speak French. Who were the people you first got to know?

Well, painters---Leonor Fini, another named Stanislao Lepri, and then a Pole who was more of a critic named Kot Jeleński. And it's very strange, because we spoke Italian at home here, when I was living with them.

Did you already know Italian from your family?

No, because my family only spoke the Piedmont dialect. Moreover, they didn't want their children to learn.

Then you learned as an adult?

Yes, when I was around twenty.

So, you spoke Italian at home here . . .

Yes, all day long practically, except with visitors. And among the visitors, well, there were very exciting people, like Audiberti, like Marcel Jouhandeau. It was an atmosphere where the criticism was permanent, to excess.

Did it bother you to publish your books in the foreign language first, in French, before they came out in their original language, Spanish?

Oh, that didn't really matter. What counted for me was to establish myself here, to be recognized here.

Once you started writing your commentaries for journals here, did you feel a special sort of responsibility, being a foreigner, to master the language even better?

But of course! Even still, I'm always afraid, especially with the articles. Because the article is irreparable. I get very anxious with them. It's like stage fright.

Do you still write them regularly?

At most I write two articles a month. You know, they think that I'm cultivated, it's not true. But as a good Argentine, I learned to read books from different literatures. So I know where to situate writers. Above all, they give me the work of foreigners. Clearly, foreigners get forgotten, we have to always resituate them.

You are a rather successful writer here in France. There have been many articles on you, your books have won important prizes. How have you lived your success?

I've never bothered about making a career. I just wanted my books to be recognized. But I'm incapable of wanting to make a career. I'm always someone who is beginning. I don't feel at all that I've arrived, not at anything. Yes, I know something's been attained, but which makes its demands. Of course, if I had never been recognized, I might be very unhappy. But at the same time, it demands a lot.

Have there been writers who were particularly important for you here?

Yes, the most important for me was Nathalie Sarraute.

Were you good friends with her?

Yes, yes. I haven't seen her in more than a year, but . . . I've written a lot on her as well. I was absolutely fascinated when I read her for the first time. My second book was an absolute imitation.

Have you ever returned to Argentina since living in France?

I went back once, in 1970, to see my father and mother---my father especially, who was very old, 86. I spent two weeks there. It was a fairly peaceful time, before the military again, before Videla and all that, and I hardly saw anything. Buenos Aires is a great city, I think that if I wasn't Argentine I would like Buenos Aires very much. I have too many memories. On the other hand, I don't go to Argentina because I'm a little afraid of losing my small savings of memories---even transformed by imagination.

Have you been back to Spain since you began publishing?

Spain? I hate that country. But you know, that's an Argentine custom, hating Spain.

But don't you feel close in one way or another to certain things in Latin American or Spanish-speaking culture?

No doubt. I feel very comfortable in Barcelona. But for me, Barcelona wasn't part of Spain. On the other hand, what I like about Latin America is that there is no cultural system. Since we have no past, we take from everywhere. The most extreme case, when they say Borges is a European writer, it's just the opposite. In Europe it's inconceivable, that way of making a sort of sauce with everything. A European belongs to a closed culture---he's French, English, German, Italian.

Have your Italian roots been particularly important to you? Have they entered into your work in some way?

Yes! When I began writing my long novel in French, in 1983.

Sans la miséricorde du Christ.

Yes. After four months in Paris, I thought perhaps I've lost one language and the other won't accept me. I was a bit disturbed. My friends at Gallimard said, Why don't you go to the Piedmont region? I had always refused to go to Piedmont for fear of meeting Bianciottis. It's full of Bianciottis. Finally, I went to the village where my father was born, and it was terrific.

Do you think that nostalgia has counted much for you?

Yes, yes. I think there are two muses that are very important for the writer, nostalgia and remorse.

When you think of nostalgia, is it for your childhood?

No, my childhood was horrible! A nightmare. Because the Argentine plains extend to infinity on all sides, a flat infinity, flat as this floor. I used to ride a horse as a boy, at full gallop, and I would feel anxious that the horizon was receding, that we couldn't escape what was infinitely open. We can leave what is closed perhaps. But we cannot leave what is open. And that's where I'm very Argentine, because that was a decisive experience. That, and hunger. Hunger in Italy.

Learning to write in a new language. Do you think it might be comparable to finding a new religion?

It's another vision of reality, yes. If I say, for example, the word oiseau, in French the word is very soft. We feel the softness of the feathers and a sort of warmth, we'd say that the French bird has never left its nest. And if you say "bird" in Spanish, you say pájaro. It takes off like an arrow. Those are two visions of reality! You sense that quite well when you belong to two languages, that the same word does not mean exactly the same thing.

After so long away, how do you see your sense of belonging?

I feel like I didn't leave Argentina to come to Europe, but to have returned to Europe. All the same, I feel best in France. The French are not very friendly, but I can say that they're more civilized.

Do you feel you have a sort of identity as a foreigner?

I have a strong accent in French. So, the moment I open my mouth, I know that to the other person I'm a foreigner. They always take me for someone from Eastern Europe. Yes, I do feel a bit like a foreigner, because I always feel a bit deaf concerning the language, I'm always afraid of making a mistake. In any case, I find it very pleasant not belonging. I don't want to belong to any group.

When you write, do you work a lot with dictionaries?

Oh, yes. I still work with dictionaries. It's become a habit now, because I have the words, but where I might gain a finer nuance, I look to see that I'm not missing anything. Or I'll find among writers who are very different---Claudel, Valéry, Jouhandeau---an expression that sounds strange, and because I like it I'll consult the Dictionnaire des difficultés du français. So, I can see that it's an expression that's fallen out of use. And there are mysteries that interest me a lot---it's a foreigner who sees these things---like how, all of a sudden, does an error get introduced into the spoken language, and everyone says it?

Your last book, Ce que la nuit raconte au jour, do you consider it a novel or more of a memoir?

It's what I called an autofiction. There are very biographical things, and things that are invented. But I think that autobiography is impossible if one is a writer. Because there's nothing to be done. Your memory offers flat images, like photographs. Something very important that lasted for years can end up reduced to a few moments. So, you describe a character who was crucial for you, but at the same time you linger because there's the light that counts, because there's the wind that blows, because this or that. When one has learned to handle words, when one has developed a taste for words, for cadences, for the phrase, there's nothing to be done, one lies. One lies.

How has music been important for you?

When we speak of music, there is also a music of language. It comes from the same thing. One has the sense of cadences, and even of melody, when one writes. Like a musician. Which is related to syntax, and also metrics. I think there's a secret metrics in prose: I've found the phrase, but the last word has three syllables, I need a word with two syllables. I am that sort of writer. I sacrifice a word, I change the meaning. An idea is modified because a word that we weren't expecting has entered the phrase like a little king and the phrase ends up obeying.

But I think if music has influenced me, it's in the structure. The fact of having listened so much and even played sonatas, often in four movements, I think that's been very important. Because in my books, I hate always keeping the same rhythm. So, I cut the rhythm the moment it becomes monotonous, I make short sentences, almost banal, then I take up another rhythm. But also, if in a book I imagine will be three hundred pages, at page eighty there's a very strong scene, there has to be a very strong scene eighty pages from the end. I think that too comes from music.

Also, there's the atmosphere of music. When I write, I listen to almost no music at all. On the other hand, before the book there's a music I listen to untiringly for months. Silvina Ocampo adored Brahms, I couldn't take him. One day I was rereading a book of her stories, and I fell upon a sentence where she says, "There is nothing more beautiful than the stories of Kafka or the love waltzes of Brahms." And that's the tone of the book I'm writing now. I adore the rhythm of the waltz. But, what's more, Brahms is the first where the waltz is going along and then it turns towards something else. So, it's never a real waltz. It's something you find much later as well in Richard Strauss.