Rzewski's Play of Faith

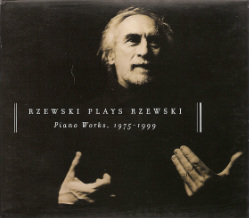

Frederic Rzewski, Rzewski Plays Rzewski: Piano Works, 1975-1999 (Nonesuch)

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 3 (Spring 2003)_

The greatest move that Frederic Rzewski ever made for his music was to leave the country as a young man. Living in Europe for most of the past four decades, first Italy and later Belgium, opened him up to the world, which then found its way back into his approaches to making music. From a distance he was better able to assess what counted for him in his native culture and to combine that with what he discovered in his new home. Thus, in his self-imposed exile, he has composed a body of work that is remarkable for its courage and breadth of vision and that places him solidly in the lineage of American modernists like Ives, Cowell, and the Seegers (Charles, Ruth Crawford, and even Pete).

The release of a 7-CD box set of new performances, Rzewski Plays Rzewski: Piano Works, 1975-1999 (Nonesuch), is therefore a major event. Arranged not chronologically but by a sort of sympathetic arc, the set opens with North American Ballads (1978-79), four pieces based on traditional labor and protest songs. From the first delicate bars of “Dreadful Memories,” and as if in counterpoint to the tragic origins of the song, Rzewski finds a way to beat swords into ploughshares, to transform sorrow and struggle into occasions of strength, beauty, revelation. In “Which Side Are You On?” and “Down by the Riverside,” which he probes more at length, he invokes as well the soul-stirring spirit those songs produced in the social movements of their time; likewise, “Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues” seems to reproduce the very pistons of the labor machine before dissolving into light.

One of Rzewski’s recurring methods of constructing a piece is to unfold a sequence of variations on a popular or traditional tune. A practice familiar to composers since before Bach, the approach is also common to jazz musicians: in both realms, improvisation offers a key to developing the possible implications of the initial lines. Indeed, Rzewski writes frameworks for improvisation into many of his pieces. 36 Variations on “The People United Will Never Be Defeated” (1975), based on a Chilean resistance song popularized by the group Quilapayún, was his first full application of this method. The tune, given a bold straightforward presentation at the start, is taken through an incredible range of metamorphoses, and just when it seems to have been rendered most abstract, aspects of the original melody filter back in, only to be stretched, deepened, recast, through further dimensions still.

Listening to this piece, it becomes clear just how well-versed Rzewski is---both as pianist and composer---in the whole expressive range of classical music. Certainly he studied with some of the best teachers, and early friendships with Christian Wolff and David Behrman were crucial. Then in the mid-1960s in Rome, with Alvin Curran and Richard Teitelbaum, he co-founded the experimental music collective Musica Elettronica Viva, eventually performing as well with jazz musicians like Steve Lacy and Anthony Braxton. But Rzewski has no need to show off his command of techniques, nor has he any stylistic axe to grind, except to be able to draw on all his resources as he sees fit. Shifts from one variation to the next may follow no apparent logic other than the will to surprise or discover, yet the more we as listeners take that journey, the more we see that the generating seed, the song---through its tonalities and mood, its harmonic and rhythmic relationships---is never lost from view. He achieves this once more in Mayn Yingele (1988-9), with its 24 variations on a traditional Yiddish tune (its lyrics about a father in the New York sweatshops who never gets to be with his son), where his virtuosity turns reflective in the flight from tenderness to indignation and, again, transcendence.

In the approximate middle of the set, taking up two discs, Rzewski embarks on his most ambitious work for piano with the first four parts of The Road (1995-97): “Turns,” “Tracks,” “Tramps,” “Stops” (he has since composed at least three of the remaining four parts---“A Few Knocks,” “Traveling with Children,” “Final Preparations”). He likens the work to a novel, for its narrative thrust and the influence of 19th-century Russian novels, but more in that its primary aim is to be read or played “by a single person alone in a room, at a speed and for a duration determined by that person, independently of the conventions of concert performance.” Each of the eight parts is divided into eight movements or “miles,” which sometimes draw on other sources, as in the second part (“Tracks”), a series of 64 variations on the railroad blues “900 Miles.” In this instance, the original tune is glimpsed as an oblique tonal coloring that lends an unpredictable charge to the music, almost surfacing at one point as a lonesome whistling against a slow gathering of raincloud chords, until well into the last movement it takes on a marvelous locomotion. Nonetheless, here as elsewhere in The Road, Rzewski subverts any easy sense of conclusiveness---other than the sound of his footsteps going toward and away from his piano at the beginning and end of this work---for inevitably the road goes on, promising further episodes.

An instinct for the dramatic has long informed Rzewski’s approach to music. His use of varied techniques (including vocal and other sound effects) proceeds by a syntax of contrasts---the build and release of tension, the juxtaposition of textures culled from different traditions, a plane of muted shades followed by a splash of color. But the dramatic element is also heightened by the agency of texts, either implied (the unsung lyrics behind the labor songs) or actually recited. Of his early vocal pieces, Coming Together (1972), excerpted from the letter of a political prisoner at Attica, showed how potent the careful setting of words could be. De Profundis (1992), on the last disc of the set, arranges passages from Oscar Wilde’s magnificent prison letter in 1897 to his unworthy lover, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, spoken and played by the composer. One of Rzewski’s most moving works, his evident political convictions are given their highest poetry here in Wilde’s deep empathy for the prisoner’s sufferings, his inquiries into the nature of love and the soul’s mysteries, and his stubborn willingness in spite of all to look toward the future. Yet the text would stay locked away on the page were it not for the authority of Rzewski’s delivery. As performer, he breathes new life into the words as the piano punctuates and measures out the phrases, casting just the right light at each moment, framing the emotion in such a way that in the end the music itself seems to speak.