_

Maxine McGregor, Chris McGregor and the Brotherhood of Breath

Flint, MI: Bamberger Books, 1995

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 3 (Spring 2003)

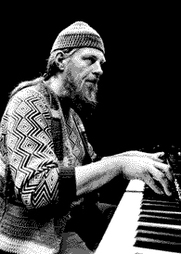

One of the great stories of modern music, a jazz story made not in the USA, the odyssey of South African pianist Chris McGregor (1936-1990) and his bandmates in the Blue Notes (saxophonist Dudu Pukwana, trumpeter Mongezi Feza, bassist Johnny Dyani, drummer Louis Moholo) has all the markings of a hero’s journey. McGregor, the son of Scottish missionaries, grew up in the Transkei, one of the designated homelands, where he soaked up the local music heard all around him. In 1963, in Johannesburg, he formed the Blue Notes, a hard-driving bop-inspired group in which he was the only white guy. After touring South Africa in difficult conditions, they left for Europe a year later and eventually settled in London. The band quickly moved beyond bop to incorporate a more South African sound rooted in popular forms like mbaqanga. Struggling constantly to make a place for themselves as foreigners, the Blue Notes became known for their infectious melodies and fiery solos among avant-garde circles in the London scene. But McGregor was hard put to keep the band together, and in 1970 he created his now-legendary big band, the Brotherhood of Breath. Uniting South African players with European, the Brotherhood was a powerhouse of horns and rhythms that made passionate listeners of almost anyone who heard them. Though it was not easy to maintain financially as a regular working unit, even after moving to the French countryside with his family in the mid-1970s McGregor reconstituted the band every few years as opportunity presented itself. This book, by McGregor’s wife Maxine, is still the best single source about the vicissitudes and triumphs of these South African exiles, all but one of whom died way too young. Maxine remains clear-eyed and unsentimental throughout, even when describing so warmly the life she shared with Chris McGregor for 27 years, drawing on testimony from the musicians themselves and from many friends, in recalling that joy created anew at every turn by the music and the vision that produced it. And thanks to her and others’ efforts, that music is slowly becoming available again through recent reissues and previously unreleased recordings (The Blue Notes’ Township Bop, from Cape Town in 1964, on Proper; the Brotherhood’s 1973 Bremen concert, Travelling Somewhere, on Cuneiform).

Maxine McGregor, Chris McGregor and the Brotherhood of Breath

Flint, MI: Bamberger Books, 1995

published in Shuffle Boil (Berkeley) 3 (Spring 2003)

One of the great stories of modern music, a jazz story made not in the USA, the odyssey of South African pianist Chris McGregor (1936-1990) and his bandmates in the Blue Notes (saxophonist Dudu Pukwana, trumpeter Mongezi Feza, bassist Johnny Dyani, drummer Louis Moholo) has all the markings of a hero’s journey. McGregor, the son of Scottish missionaries, grew up in the Transkei, one of the designated homelands, where he soaked up the local music heard all around him. In 1963, in Johannesburg, he formed the Blue Notes, a hard-driving bop-inspired group in which he was the only white guy. After touring South Africa in difficult conditions, they left for Europe a year later and eventually settled in London. The band quickly moved beyond bop to incorporate a more South African sound rooted in popular forms like mbaqanga. Struggling constantly to make a place for themselves as foreigners, the Blue Notes became known for their infectious melodies and fiery solos among avant-garde circles in the London scene. But McGregor was hard put to keep the band together, and in 1970 he created his now-legendary big band, the Brotherhood of Breath. Uniting South African players with European, the Brotherhood was a powerhouse of horns and rhythms that made passionate listeners of almost anyone who heard them. Though it was not easy to maintain financially as a regular working unit, even after moving to the French countryside with his family in the mid-1970s McGregor reconstituted the band every few years as opportunity presented itself. This book, by McGregor’s wife Maxine, is still the best single source about the vicissitudes and triumphs of these South African exiles, all but one of whom died way too young. Maxine remains clear-eyed and unsentimental throughout, even when describing so warmly the life she shared with Chris McGregor for 27 years, drawing on testimony from the musicians themselves and from many friends, in recalling that joy created anew at every turn by the music and the vision that produced it. And thanks to her and others’ efforts, that music is slowly becoming available again through recent reissues and previously unreleased recordings (The Blue Notes’ Township Bop, from Cape Town in 1964, on Proper; the Brotherhood’s 1973 Bremen concert, Travelling Somewhere, on Cuneiform).