_

Blue Notes, The Ogun Collection

London: Ogun Records, 2008

published in Signal to Noise (Houston) 53 (Spring 2009)

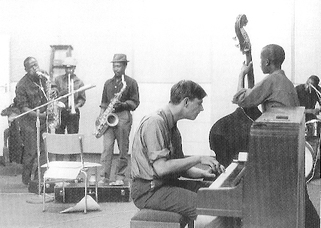

Considering the phenomenon that was the Blue Notes, it’s amazing that the band went unrecorded during their first years in Europe. A mixed-race group, they were predominantly a hard bop outfit when they escaped the tightening restraints of South African apartheid to play the Antibes festival in the summer of 1964. Through exposure to the most adventurous players in the new music, they soon transformed into an avant-garde unit, with their own distinct energy and drive. After stints in Zurich, Geneva, and Copenhagen, they eventually settled for a while in London, where they had a lasting impact on a whole generation of improvising musicians. And yet, known mostly as a quintet--- Dudu Pukwana (alto saxophone), Chris McGregor (piano), Louis Moholo (drums), Mongezi Feza (trumpet), Johnny Dyani (bass)---they never appeared as such on record.

Even so, the full force of that quintet is felt implicitly throughout The Ogun Collection, the long-awaited five-CD set that reissues all but the earliest documents of the band, with unreleased material that restores complete sessions. Though the band had effectively broken up as a working ensemble by the late ‘60s, still it reunited occasionally: the Ogun box demonstrates their unique longevity, that of a family bond forged in exile. And like a family, their number dwindled through the quarter century spanned by these recordings.

On Legacy: Live in South Afrika 1964, the Blue Notes are heard in their original formation as a sextet with the authoritative tenor saxophonist Nick Moyake (who made the journey to Europe but returned home the next year). Already the musicians are reaching toward open terrain in these extended performances, from a concert in Durban shortly before their departure, in contrast to the more contained studio sessions (Township Bop) months earlier. Pukwana really lets it rip on his own “Two for Sandi”; Feza, in turn, offers a glimpse of his nimble grace on McGregor’s “Vortex Special.” Behind the stylistic influences anchoring them to the jazz tradition, amid the interstices, the kernel of their future flowering is clearly found there.

Many musical enterprises later, the band recorded again in studio at the end of 1975, as a quartet, barely a week after Feza’s untimely death. A double-disc marathon, Blue Notes for Mongezi sets out wailing and very free, moving in and out of themes drawn from each member’s individual projects, and builds, mournful and reflective, to an indomitable spirit of celebration. Totally spontaneous, the musicians just played, washing through them entire lifetimes of music and emotion. Often singing or chanting, fiercely melodic, even a little raw, their tunes take on the aspect of praise songs. Above all, no matter the distance between them by then (McGregor in France, Dyani in Scandinavia), their intuitive cohesion remains strong.

In the spring of 1977, the quartet played a familiar London venue, the 100 Club. Blue Notes in Concert reconfirms the special sympathy they shared, and makes evident the worlds traversed since their initial live recording. Paradoxically, as may happen in the crucible of exile, they sound more deeply South African than when they lived there: through these years, memory and imagination conspired to transpose the voicings they grew up with---from church hymns to folk songs to popular music---into new forms ever at the edge of wildness, full of lyrical uplift and rousing rhythmic subtleties. For all of them, this was the decade in which they achieved their sublime synthesis.

The final set in the marvelous Ogun box marks a further loss. Blue Notes for Johnny, recorded in 1987 the year after Dyani’s death, features a trio that even masquerades as a quartet once, by the tricks of studio magic---Pukwana on alto and soprano playing in tandem (“Funk Dem Dudu”). Still, their presence as a trio is commanding enough that they sound like more. Unlike on the other sessions, the repertoire is mostly given over to Dyani’s own impassioned melodies, again rendering celebration from sorrow. Such was the miracle of the Blue Notes that every occasion for making music turned into a revelation of joy.

Blue Notes, The Ogun Collection

London: Ogun Records, 2008

published in Signal to Noise (Houston) 53 (Spring 2009)

Considering the phenomenon that was the Blue Notes, it’s amazing that the band went unrecorded during their first years in Europe. A mixed-race group, they were predominantly a hard bop outfit when they escaped the tightening restraints of South African apartheid to play the Antibes festival in the summer of 1964. Through exposure to the most adventurous players in the new music, they soon transformed into an avant-garde unit, with their own distinct energy and drive. After stints in Zurich, Geneva, and Copenhagen, they eventually settled for a while in London, where they had a lasting impact on a whole generation of improvising musicians. And yet, known mostly as a quintet--- Dudu Pukwana (alto saxophone), Chris McGregor (piano), Louis Moholo (drums), Mongezi Feza (trumpet), Johnny Dyani (bass)---they never appeared as such on record.

Even so, the full force of that quintet is felt implicitly throughout The Ogun Collection, the long-awaited five-CD set that reissues all but the earliest documents of the band, with unreleased material that restores complete sessions. Though the band had effectively broken up as a working ensemble by the late ‘60s, still it reunited occasionally: the Ogun box demonstrates their unique longevity, that of a family bond forged in exile. And like a family, their number dwindled through the quarter century spanned by these recordings.

On Legacy: Live in South Afrika 1964, the Blue Notes are heard in their original formation as a sextet with the authoritative tenor saxophonist Nick Moyake (who made the journey to Europe but returned home the next year). Already the musicians are reaching toward open terrain in these extended performances, from a concert in Durban shortly before their departure, in contrast to the more contained studio sessions (Township Bop) months earlier. Pukwana really lets it rip on his own “Two for Sandi”; Feza, in turn, offers a glimpse of his nimble grace on McGregor’s “Vortex Special.” Behind the stylistic influences anchoring them to the jazz tradition, amid the interstices, the kernel of their future flowering is clearly found there.

Many musical enterprises later, the band recorded again in studio at the end of 1975, as a quartet, barely a week after Feza’s untimely death. A double-disc marathon, Blue Notes for Mongezi sets out wailing and very free, moving in and out of themes drawn from each member’s individual projects, and builds, mournful and reflective, to an indomitable spirit of celebration. Totally spontaneous, the musicians just played, washing through them entire lifetimes of music and emotion. Often singing or chanting, fiercely melodic, even a little raw, their tunes take on the aspect of praise songs. Above all, no matter the distance between them by then (McGregor in France, Dyani in Scandinavia), their intuitive cohesion remains strong.

In the spring of 1977, the quartet played a familiar London venue, the 100 Club. Blue Notes in Concert reconfirms the special sympathy they shared, and makes evident the worlds traversed since their initial live recording. Paradoxically, as may happen in the crucible of exile, they sound more deeply South African than when they lived there: through these years, memory and imagination conspired to transpose the voicings they grew up with---from church hymns to folk songs to popular music---into new forms ever at the edge of wildness, full of lyrical uplift and rousing rhythmic subtleties. For all of them, this was the decade in which they achieved their sublime synthesis.

The final set in the marvelous Ogun box marks a further loss. Blue Notes for Johnny, recorded in 1987 the year after Dyani’s death, features a trio that even masquerades as a quartet once, by the tricks of studio magic---Pukwana on alto and soprano playing in tandem (“Funk Dem Dudu”). Still, their presence as a trio is commanding enough that they sound like more. Unlike on the other sessions, the repertoire is mostly given over to Dyani’s own impassioned melodies, again rendering celebration from sorrow. Such was the miracle of the Blue Notes that every occasion for making music turned into a revelation of joy.