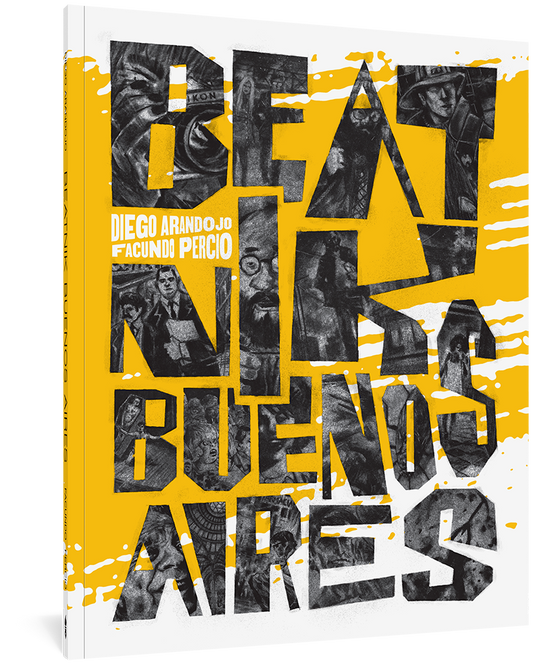

Beatnik Buenos Aires

Diego Arandojo and Facundo Percio

Translated by Andrea Rosenberg

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2021

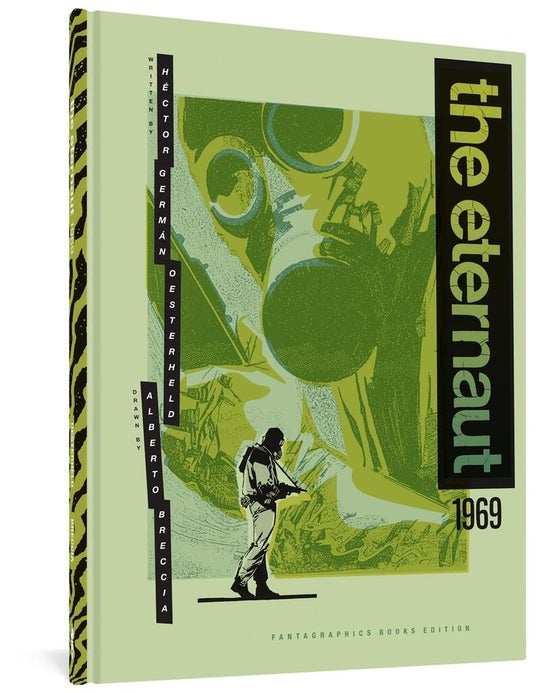

The Eternaut 1969

Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Alberto Breccia

Translated by Erica Mena

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2020

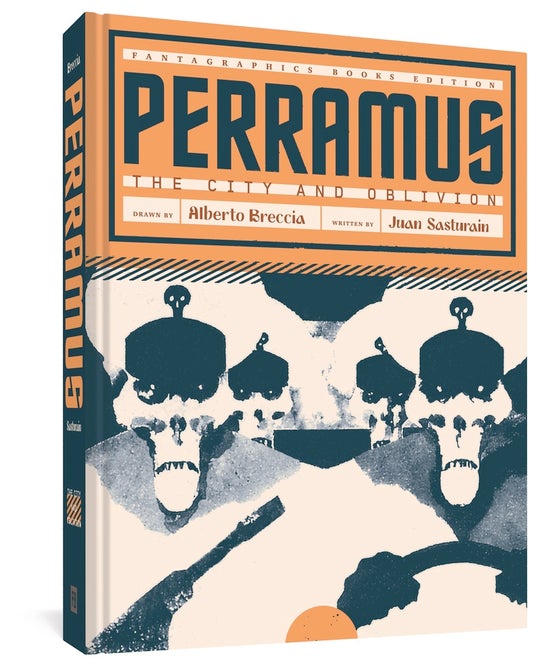

Perramus: The City and Oblivion

Juan Sasturain and Alberto Breccia

Translated by Erica Mena

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2020

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 103 (December 2021)

The latest Argentine offering from Fantagraphics, the veteran Seattle-based publisher of comics and graphic novels, Beatnik Buenos Aires is set in the mid-1960s among the artists, writers, and misfits who frequented the Bar Moderno and other haunts downtown, especially the legendary art performance space the Instituto Di Tella. The book appeared in Spanish in 2018, sprung from a constellation of anecdotes gathered by writer Diego Arandojo that he could not fit into a documentary he was making about the Opium literary group. The eccentric founders of Opium—Ruy Rodríguez, Reynaldo Mariani, Sergio Mulet—typify the thirteen subjects glimpsed in brief chapters that build a vivid impression of porteño nightlife at the time. Each figure is their own grand performance, starting with Ithacar Jalí, a volunteer fireman, occultist, and artist devoted to the transformative powers of fire, who had a bit of a following; or the ace art forger known pseudonymously as Goldie, with her long, straight blonde hair, who can copy all the modern Argentine painters and takes her new lover out to the suburbs one night to see the paintings of her friend, none other than Ernesto Sábato. Other stars of the artistic firmament make cameo appearances as well, like the painter Antonio Berni who is asked to donate a work to be auctioned as support for a young theater duo in their upcoming tour, and Borges himself, in the penultimate chapter, which focuses on the literary publisher and designer Juan Ioannis Andralis with his El Archibrazo imprint. The chapters, in their visual and narrative economy, portraying just one or two episodes in the trajectory of each subject, may seem almost too brief and elliptical for the casual reader, but to that end there is an important appendix that provides a second layer of information, with several paragraphs for each chapter filling in more about the characters. The artist Facundo Percio, his scenes brimming with atmosphere, shows a sharp instinct for portraiture as well as more ethereal aspects, and a flare for the dramatic moment. Since I had never heard of most of the characters, I sent a note with their names to my old friend Luisa Futoransky, now forty years in Paris, who is of the same generation and moved in similar circles back then: she replied that she knew every one of them and offered me contact details for those who were still alive.

El Eternauta (1957-59; The Eternaut, 2015), a landmark in Argentine graphic literature, written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Francisco Solano López, has seen many editions domestic and foreign. Originally a serial in a weekly comics supplement, it chronicles an alien invasion heralded by a deadly, iridescent snow over Buenos Aires (where snow is rare), and the group of survivors who fight against impossible odds to save not only themselves but the world. Just when all seems finally lost, the narrator, Juan Salvo, trying to gain control of their machines, accidentally casts himself into another realm entirely and so he ends up a traveler of eternity; one night, he materializes to the author, across from him at his table, a few years before the events and in the same neighborhood as it turns out, and there he tells his nightmare of a story. Among the many resonances the work stirred in its time, the advanced technology of the North is seen in the long-range missiles streaking across the night sky late in the struggle, likely sign of a powerful ally; but those are nuclear missiles and one lands downtown, destroying Buenos Aires, though not the end for our intrepid survivors. Through the 1960s, Oesterheld’s political convictions deepened and when he had the opportunity to write a remake, a decade later, the Northern powers play an even more ominous role: they have betrayed South America entirely to the alien invaders. The Eternaut 1969 is thus a darker take on the tale, in an increasingly more perilous era. But it is also a curious creature: this time, the work first appeared in a weekly gossip magazine, except it was canceled after four months, due to its poor reception. Already a more economical retelling, especially in the last episodes where a lot had to suddenly be fit in, the book still packs almost as much heft in fifty pages as the original did in 350 (the 2015 translation). Certainly, the many twists and turns of the original are a delight, carried by Solano López’s naturalistic, richly imagined illustrations, but the later version gained new dimensions as drawn by the brilliant Uruguayan-born artist Alberto Breccia, whose chiaroscuro, experimental style veered into expressionistic, collage, and abstract techniques to great effect. Oesterheld eventually joined the Montoneros in the mid-1970s, after his four daughters did, and like them he ended up disappeared by the military dictatorship; yet before that, in 1976-77 while already in hiding, he also wrote a remarkable sequel (El Eternauta. Segunda parte), sending in his installments from secret locations for Solano López to illustrate on his own. Three-plus decades later, Lucrecia Martel tried to make a film adaptation of the original work but had to abandon the project, and now at long last, Netflix is producing a TV series in Argentina based on the book.

Fantagraphics launched the ongoing Alberto Breccia Library with an earlier collaboration he did with Oesterheld, Mort Cinder, another time traveler. The latest (fourth) volume is Alberto Breccia’s Dracula, stories without text composed during the end of the Argentine dictatorship (1982-83), to be followed by two other late-‘60s books with Oesterheld, Life of Che and Evita. The second in the Breccia collection, the feast that is Perramus, which he initiated with the younger writer Juan Sasturain, also began in 1982 but grew to four books by 1989. The first of those books, understandably, is particularly weighted with shadows, the “marshals” running the country seen everywhere as skulls in uniform, abetted by sundry fat cats and American advisors. Among the rebels and revolutionaries, pursuing intrigues of their own, are the core trio, starting with the title character who woke up in a woman’s bed with no memory, whose name is simply what’s found on the label in the used mackintosh she gave him. He soon joins forces with the Afro-Uruguayan former meatpacker Canelones and the airplane pilot known as Enemy, in circumstances that eventually lead them to the underground’s surprise liaison Borges, in a supporting role, like a master of ceremonies to their adventures, a wise if wily elder. In the second and fourth books especially, he guides them first in a search to rescue and secure the soul of the city, by tracking down certain unknown figures in various neighborhoods who turn out to be the bearers of that soul; and, in the final book, summoned by Gabo to Medellín and assisted by Borges, they must embark on a quest across continents to find the long-missing teeth that belong in Gardel’s exhumed skull (who died in a 1935 plane crash in Medellín), and thus to restore his smile. Along the way, amid playful references to El Eternauta, the authors get to reimagine the historical Borges and grant him the Nobel Prize. Through more than 450 pages, Breccia’s ever resourceful art proves edgy and dynamic, steeped both in popular culture tropes and the sophisticated graphic techniques of the great innovators.

Diego Arandojo and Facundo Percio

Translated by Andrea Rosenberg

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2021

The Eternaut 1969

Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Alberto Breccia

Translated by Erica Mena

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2020

Perramus: The City and Oblivion

Juan Sasturain and Alberto Breccia

Translated by Erica Mena

Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2020

published in Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas (New York) 103 (December 2021)

The latest Argentine offering from Fantagraphics, the veteran Seattle-based publisher of comics and graphic novels, Beatnik Buenos Aires is set in the mid-1960s among the artists, writers, and misfits who frequented the Bar Moderno and other haunts downtown, especially the legendary art performance space the Instituto Di Tella. The book appeared in Spanish in 2018, sprung from a constellation of anecdotes gathered by writer Diego Arandojo that he could not fit into a documentary he was making about the Opium literary group. The eccentric founders of Opium—Ruy Rodríguez, Reynaldo Mariani, Sergio Mulet—typify the thirteen subjects glimpsed in brief chapters that build a vivid impression of porteño nightlife at the time. Each figure is their own grand performance, starting with Ithacar Jalí, a volunteer fireman, occultist, and artist devoted to the transformative powers of fire, who had a bit of a following; or the ace art forger known pseudonymously as Goldie, with her long, straight blonde hair, who can copy all the modern Argentine painters and takes her new lover out to the suburbs one night to see the paintings of her friend, none other than Ernesto Sábato. Other stars of the artistic firmament make cameo appearances as well, like the painter Antonio Berni who is asked to donate a work to be auctioned as support for a young theater duo in their upcoming tour, and Borges himself, in the penultimate chapter, which focuses on the literary publisher and designer Juan Ioannis Andralis with his El Archibrazo imprint. The chapters, in their visual and narrative economy, portraying just one or two episodes in the trajectory of each subject, may seem almost too brief and elliptical for the casual reader, but to that end there is an important appendix that provides a second layer of information, with several paragraphs for each chapter filling in more about the characters. The artist Facundo Percio, his scenes brimming with atmosphere, shows a sharp instinct for portraiture as well as more ethereal aspects, and a flare for the dramatic moment. Since I had never heard of most of the characters, I sent a note with their names to my old friend Luisa Futoransky, now forty years in Paris, who is of the same generation and moved in similar circles back then: she replied that she knew every one of them and offered me contact details for those who were still alive.

El Eternauta (1957-59; The Eternaut, 2015), a landmark in Argentine graphic literature, written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Francisco Solano López, has seen many editions domestic and foreign. Originally a serial in a weekly comics supplement, it chronicles an alien invasion heralded by a deadly, iridescent snow over Buenos Aires (where snow is rare), and the group of survivors who fight against impossible odds to save not only themselves but the world. Just when all seems finally lost, the narrator, Juan Salvo, trying to gain control of their machines, accidentally casts himself into another realm entirely and so he ends up a traveler of eternity; one night, he materializes to the author, across from him at his table, a few years before the events and in the same neighborhood as it turns out, and there he tells his nightmare of a story. Among the many resonances the work stirred in its time, the advanced technology of the North is seen in the long-range missiles streaking across the night sky late in the struggle, likely sign of a powerful ally; but those are nuclear missiles and one lands downtown, destroying Buenos Aires, though not the end for our intrepid survivors. Through the 1960s, Oesterheld’s political convictions deepened and when he had the opportunity to write a remake, a decade later, the Northern powers play an even more ominous role: they have betrayed South America entirely to the alien invaders. The Eternaut 1969 is thus a darker take on the tale, in an increasingly more perilous era. But it is also a curious creature: this time, the work first appeared in a weekly gossip magazine, except it was canceled after four months, due to its poor reception. Already a more economical retelling, especially in the last episodes where a lot had to suddenly be fit in, the book still packs almost as much heft in fifty pages as the original did in 350 (the 2015 translation). Certainly, the many twists and turns of the original are a delight, carried by Solano López’s naturalistic, richly imagined illustrations, but the later version gained new dimensions as drawn by the brilliant Uruguayan-born artist Alberto Breccia, whose chiaroscuro, experimental style veered into expressionistic, collage, and abstract techniques to great effect. Oesterheld eventually joined the Montoneros in the mid-1970s, after his four daughters did, and like them he ended up disappeared by the military dictatorship; yet before that, in 1976-77 while already in hiding, he also wrote a remarkable sequel (El Eternauta. Segunda parte), sending in his installments from secret locations for Solano López to illustrate on his own. Three-plus decades later, Lucrecia Martel tried to make a film adaptation of the original work but had to abandon the project, and now at long last, Netflix is producing a TV series in Argentina based on the book.

Fantagraphics launched the ongoing Alberto Breccia Library with an earlier collaboration he did with Oesterheld, Mort Cinder, another time traveler. The latest (fourth) volume is Alberto Breccia’s Dracula, stories without text composed during the end of the Argentine dictatorship (1982-83), to be followed by two other late-‘60s books with Oesterheld, Life of Che and Evita. The second in the Breccia collection, the feast that is Perramus, which he initiated with the younger writer Juan Sasturain, also began in 1982 but grew to four books by 1989. The first of those books, understandably, is particularly weighted with shadows, the “marshals” running the country seen everywhere as skulls in uniform, abetted by sundry fat cats and American advisors. Among the rebels and revolutionaries, pursuing intrigues of their own, are the core trio, starting with the title character who woke up in a woman’s bed with no memory, whose name is simply what’s found on the label in the used mackintosh she gave him. He soon joins forces with the Afro-Uruguayan former meatpacker Canelones and the airplane pilot known as Enemy, in circumstances that eventually lead them to the underground’s surprise liaison Borges, in a supporting role, like a master of ceremonies to their adventures, a wise if wily elder. In the second and fourth books especially, he guides them first in a search to rescue and secure the soul of the city, by tracking down certain unknown figures in various neighborhoods who turn out to be the bearers of that soul; and, in the final book, summoned by Gabo to Medellín and assisted by Borges, they must embark on a quest across continents to find the long-missing teeth that belong in Gardel’s exhumed skull (who died in a 1935 plane crash in Medellín), and thus to restore his smile. Along the way, amid playful references to El Eternauta, the authors get to reimagine the historical Borges and grant him the Nobel Prize. Through more than 450 pages, Breccia’s ever resourceful art proves edgy and dynamic, steeped both in popular culture tropes and the sophisticated graphic techniques of the great innovators.